To mark the start of LGBT+ History Month, BBC Sport looks at the lives of six LGBT+ sportspeople who made history in their respective sports, but whose stories may not be as widely known.

From the first known British transgender woman to a Wimbledon champion, an NFL Pro-Bowler and a sprinter who successfully challenged her sport’s governing body.

Here are six LGBT+ sportspeople we think you should know more about.

Warning: This article includes references to suicide, drug use and other issues such as sexual misconduct.

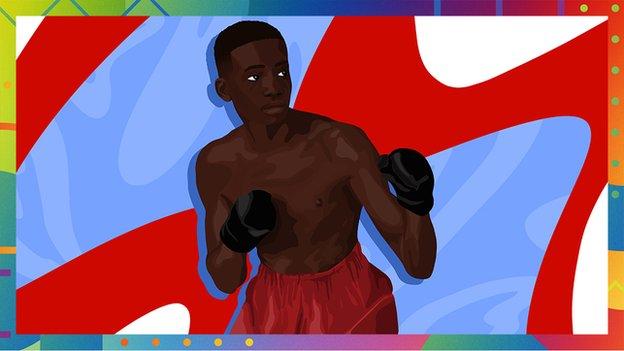

1. Panama Al Brown

Alfonso Teofilo Brown, better known as Panama Al Brown, was the first Latin American boxing world champion and is regarded as one of the greatest bantamweights in history.

During his career, Brown won an incredible 59 fights by knockout and was the bantamweight world champion for six years.

Brown was born in 1902 to Afro-Caribbean immigrant parents in Panama. His mother was a cleaner and his father died when Brown was 13 years old. As a teenager, Brown was working as a clerk at the Panama Canal Zone when he saw American soldiers boxing and decided to take up the sport.

Brown turned professional aged 20 and, the following year, won his first fight abroad in New York. He moved to the city, where his rise to the top of his sport was emphatic.

In 1926, after boxing across the USA for three years, Brown fought in Paris for the first time. He enjoyed it so much, he decided to move there.

In 1929, Brown became the first Latin American world champion when he beat Spain’s Gregorio Vidal by a 15-round decision in New York. The victory made him a hero in Panama and he became renowned around Latin America.

Brown also became a popular boxer in Paris and fought in 40 bouts around Europe between 1929 and 1934.

He spent much of his life in the French capital and was reportedly adored by the French because of his ability to speak seven languages and his all-night partying.

He performed in cabaret shows too, and even tap-danced in one that showcased black talent and launched the career of Josephine Baker.

But not everyone loved the Panamanian. Brown was in a relationship with French writer Jean Cocteau, who became his manager, despite knowing little about the sport.

When rumours of Brown’s sexuality spread, people began attending his fights just to jeer or spit at him during ring-walks, and after one fight, he was beaten unconscious by spectators.

All of this on top of the racial discrimination he already faced.

When World War Two began, Brown moved back to New York and tried to find work in cabaret clubs in Harlem, without success.

He began boxing again but was a faded force. In 1942, he was arrested for cocaine use and deported to Panama for a year.

After returning to Harlem, Brown – by now in his late 40s – got by as a sparring partner for aspiring boxers, earning a dollar per round.

Brown died of tuberculosis aged 48 in 1951. He was initially buried in a small grave in Harlem, until some boxing fans raised money to send his remains to Panama.

2. Dutee Chand

Dutee Chand, born in 1996, is the third Indian woman to qualify for the 100m at an Olympic Games, was the first Indian to reach a global sprint final – at the World Youths – and has two Asian Games silver medals. She is also the first openly gay athlete to compete for India.

Chand grew up in Chaka Gopalpur, a poor, rural village in Odisha’s Jajpur district. She came out in 2019 – a year after India’s Supreme Court decriminalised gay sex – and faced public backlash from people in her village, as well as her parents.

Chand’s father told the Times of India his daughter’s relationship was “immoral and unethical”, and she had “destroyed the reputation of [their] village.”

Her mother added: “We belong to a traditional Odia weaver community which does not permit such things. How can we face our relatives and the society?”

But the media attention wasn’t new for Chand. When she was 18 years old in 2014, she was disqualified from the Commonwealth Games because of her testosterone levels.

Like South African 800m legend Caster Semenya, Chand’s natural levels of testosterone were normally only found in men. This is also known as difference of sexual development, or DSD.

Chand missed out on competing at the Commonwealth and Asian Games in 2014 because of the suspension, refusing to subject herself to the “corrective” treatment (hormone suppression therapy) prescribed by the IAAF (now World Athletics) and the International Olympic Committee (IOC).

Fast-forward a year, and Chand became the first athlete to challenge the “hyperandrogenism rules”. They were temporarily suspended and Chand could compete again, and she went on to become an Olympian the following year. That same rule challenge was rejected for Semenya.

In 2018, Chand spoke about how she met Semenya at the Rio Games, who made her feel like a “close friend”.

“She told me not to worry about the case and to focus on the sport. I am glad that my battle is over, but hers is not,” said Chand.

In 2019, the Court of Arbitration for Sport (Cas) ruled in favour of the controversial rule, meaning athletes with DSD, like Semenya, would have to take the hormone-limiting drugs if they wanted to compete in the 400m, 400m hurdles, 800m, 1500m, one mile races and combined events over the same distances.

As a sprinter, Chand is exempt from the rule. But she reportedly offered Semenya her legal team that worked on her 2015 appeal.

During the coronavirus pandemic, Chand spent time distributing food deliveries and sanitary pads to people in her village.

She is also planning on opening an athletics academy for locals, and told Vogue: “I want another child aspiring to be a runner to run barefoot like me.”

In contrast to being banned from the 2014 Commonwealth Games, Chand was recently announced as one of four ambassadors for the Birmingham 2022 Games’ Pride House.

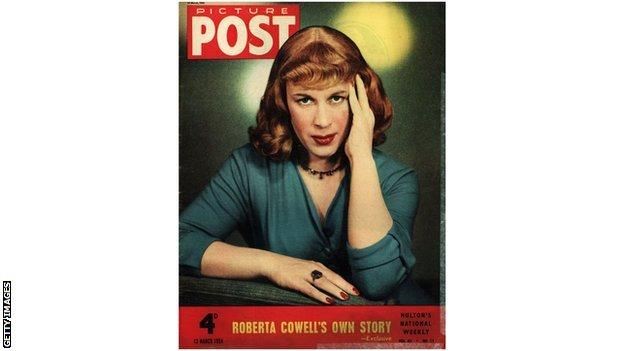

3. Roberta Cowell

Roberta Cowell, born in 1918, was a racing driver, a WW2 fighter pilot and the first known British trans woman to have sex-reassignment surgery.

Cowell’s father was Major General Sir Ernest Marshall Cowell, honorary surgeon to King George VI – the Queen’s father.

She became interested in cars and racing, saying in her biography: “It was the be-all and nearly the end-all of my existence.”

Cowell left school at 16 and would later join the RAF, but her ambition of becoming a fighter pilot was initially dashed by airsickness.

She instead started studying engineering in 1936 at University College London, where she also began pursuing her interest in motor racing.

What started as Cowell donning mechanical overalls to sneak into car service areas at Brooklands racing circuit to gain experience led to her racing alongside her studies and in 1939 she competed at the Antwerp Grand Prix.

At 23, Cowell married fellow race car driver Diana Zelma Carpenter and the couple had two daughters.

During WW2, Cowell transferred back to the RAF, working as a temporary pilot officer. In 1944, she spent five months in German prisoner of war camps after her aircraft crashed and she was captured by German troops.

Cowell raced competitively after the war but was increasingly uncomfortable with her body – by 1950 she was still living as a man, but taking large doses of oestrogen.

She met doctor Michael Dillon, the first trans man to get a phalloplasty (a construction of a penis), and he carried out an operation on Cowell to remove her testicles – a procedure that was illegal in the UK at the time.

This allowed Cowell to get a document stating she was intersex from a private gynaecologist, which enabled her to obtain a new birth certificate that stated her sex as female.

In 1951, Cowell became the first person in Britain to have a vaginoplasty (construction of a vagina out of penile tissue). It was carried out by Sir Harold Gillies, widely considered the father of plastic surgery, who has only previously performed the procedure on a cadaver.

After her transition, Cowell returned to motorsport and continued to race during the 1950s and 1960s, before running into financial problems.

Cowell died aged 93 in 2011 while living alone in south west London. She had requested there be no publicity when she died, and her daughters, who she had not seen since before her divorce decades earlier, only found out about her death two years later when an obituary was published.

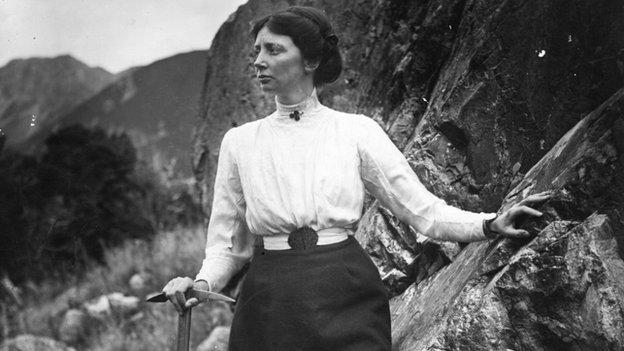

4. Freda du Faur

Freda du Faur, born in Sydney in 1882, was an Australian mountaineer who became the first woman to climb Mount Cook, New Zealand’s tallest mountain, in 1910.

Du Faur grew up near Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park where she taught herself to rock climb. She was studying to be a nurse when she received inheritance money from her aunt that allowed her to travel and become a full-time mountaineer.

Du Faur prepared for her climb of Mount Cook at a physical education institute in Sydney, where she met trainer Muriel Cadogan, who would eventually become her partner.

On 3 December 1910, guided by Peter Graham and his brother Alec, Du Faur became the first woman to climb the 3,760m tall Mount Cook, in a then-record time of six hours.

After the climb, Du Faur said: “I gained the summit – feeling very little, very lonely and much inclined to cry.”

In the following years, she climbed several other mountains, including one that was later named after her, as well as the second-highest mountain in New Zealand, Mount Tasman.

In 1914, Du Faur moved to England and lived with Cadogan in Bournemouth while writing a book about climbing Mount Cook.

In 1929, Cadogan had a nervous breakdown and Du Faur tried to admit her to a mental facility.

Instead, they were both admitted, drugged and separated against their will. Unlike male homosexuality, which was a crime, lesbianism was then classed as a psychological disorder.

Eventually, Cadogan was sent back to Sydney and took her own life on the cargo boat on the journey back.

After Cadogan’s death, Du Faur was released from the facility. She returned to Australia to live with her family, but remained confused and depressed.

Du Faur killed herself in 1935 and her family buried her in an unmarked grave. In 2006, a plaque was added to her grave site to commemorate her legacy.

As well as the mountain named after Freda, the Southern Alps of New Zealand are home to the Cadogan Peak, named after Muriel Cadogan.

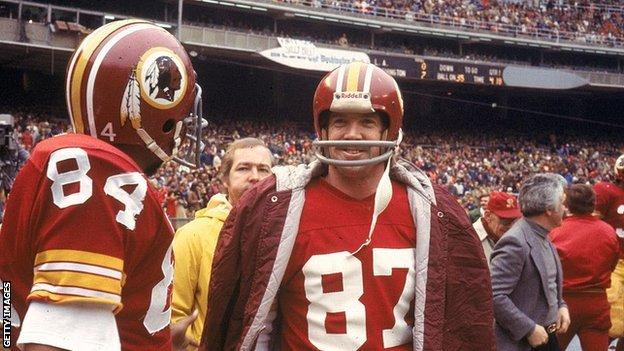

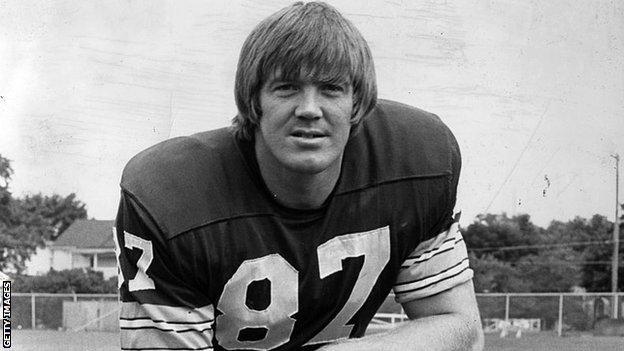

5. Jerry Smith

Jerry Smith, born in Oregon in 1943, was a tight end for the NFL’s Washington Redskins for 13 seasons. When he retired, Smith held the NFL record for most career touchdowns by a tight end (60). The two-time Pro-Bowler never publicly came out as gay before he died of Aids aged 43.

Smith was selected in the ninth round of the 1965 NFL draft by the Washington Redskins, now called the Washington Football Team. At 6ft 3in, he was considered small for a tight end. But he went on to have a long and successful career, holding various NFL records, and was widely regarded as one of the best tight ends of his time.

Smith’s record for most career touchdowns was only broken in 2003 by Shannon Sharpe, who was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2011. Smith’s close friend and team-mate Brig Owens has claimed Smith would also be in the Hall of Fame if not for his sexuality.

Smith was in a brief relationship with team-mate David Kopay, who in 1975 became the first NFL player to come out, three years after retiring.

Kopay referred to a sexual encounter with Smith, using an alias for him, in his autobiography. Smith never spoke to Kopay again.

Smith was briefly coached by NFL legend Vince Lombardi, who he loved playing for, and whose brother was openly gay.

Lombardi tried to ensure there was tolerance for everybody in the locker room, reportedly hinting to Smith that he knew about and accepted his sexuality.

Shortly before he died, Smith said: “Every important thing a man searches for in his life, I found in Coach Lombardi. He made us men.”

Owens, who often roomed with Smith, said that Smith lived in fear and never came out because he worried if people knew he was gay, his career would be ruined.

In 1986, Smith became the first professional athlete to announce he had been diagnosed with Aids. He died two months later.

A few weeks before his death, he was interviewed for an article in the Washington Post so that, as he said, ‘Middle America’ might finally accept that Aids could affect anyone. Even an NFL player.

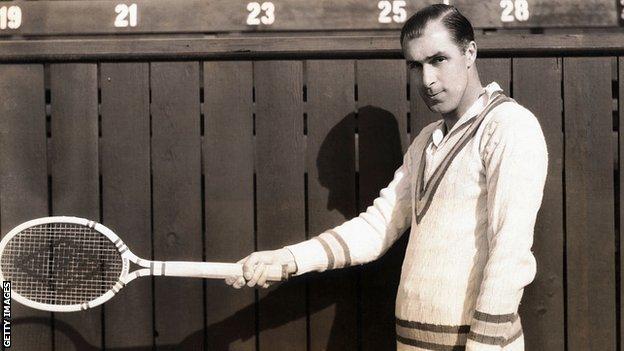

6. Bill Tilden

Bill Tilden, born in 1893, won 10 Grand Slam titles including three Wimbledon and seven US Nationals (now US Open) titles.

He dominated tennis for more than a decade, at one point winning every major tournament he entered for six years. He was also openly gay.

In 1929, Tilden became the first men’s player to reach 10 finals at a single Grand Slam event – a record which was only broken in 2017 when Roger Federer reached his 11th Wimbledon final.

Tilden was born to a wealthy family in Philadelphia. He played tennis as a child, but it wasn’t until his early 20s that he started taking the sport seriously.

By the age of 22, both his parents and his older brother had died, causing him to suffer from severe depression. Tennis became his way of coping.

Tilden became the first American man to win Wimbledon in 1920. He won again the following year and said it was “too easy”, so didn’t play at the tournament for the next three years.

In 1930, aged 37, he became the oldest man to win a Wimbledon singles title. The following year, desperately needing to earn money, Tilden began playing professionally and continued on the pro circuit into his 50s.

However, in 1946, Tilden was arrested, charged and sentenced to a year in prison for ‘contributing to the delinquency of a minor’ – although he disputed his conviction.

On his release, Tilden’s parole conditions were strict and lasted five years, and the tennis world shunned him. Tilden could no longer earn an income from giving lessons anymore – apart from when his friend Charlie Chaplin allowed him to use his private court.

Tilden was arrested again in 1949 for groping a 16-year-old hitchhiker. He served 10 months in prison.

Despite those convictions, in a 1950 Associated Press poll, Tilden was unanimously voted the greatest tennis player of the half-century. This was just weeks after being released from prison.

During the years he spent on the pro tour, Tilden lived in a suite in a New York hotel where he wrote Broadway shows that he would produce and star in, as well as books on tennis strategy. He faded from public life and in 1953, aged 60, died of heart complications.