Long before social media became a 24/7 platform for the airing of opinions, Gay Byrne offered an outlet for voices that couldn’t be heard anywhere else. For decades, on the Late Late Show and The Gay Byrne Show, the legendary broadcaster was a confidant to and a conduit for a society burdened with secrets and shrouded in shame.

Now a new documentary, Dear Gay, delves into the archives of RTÉ and excavates people’s personal letters to explore Byrne’s impact through the words of the many people who wrote to him.

Producer and director of the documentary, Sarah Ryder, says the public’s interaction with Byrne through letters is a thread that ran through his career as a broadcaster.

“We spoke to his family, people who had worked with him, people who knew him well, and what kept coming up through those conversations was the phrase ‘he got a letter’ or ‘there was a letter’.”

Ryder had previously worked on a documentary on the Ann Lovett letters, when women around the country wrote into the radio show and shared their stories in the aftermath of the tragic death of the teenager at a grotto in Granard, Co Offaly after giving birth to a stillborn baby. When Ryder returned to the archives, she found a cache of letters to the Gay Byrne Show Fund, which was set up to give financial aid listeners to people in need.

“We went through the Ann Lovett letters which took us two days. We then discovered the Gay Byrne Show Fund letters — from 1984 to 1988 there are letters from people that would absolutely break your heart, from people who had fallen into the poverty trap and were struggling to make ends meet.

“We came across one heartbreaking story of a woman whose husband was an abusive alcoholic — he deserted her and when he died, there was no-one to pay his funeral bill. She had been paying it off as much as she could, there was £300 outstanding and she wrote to the fund to ask for the remainder to be paid so she could buy Christmas presents for her children.”

Also featured in the documentary is Donal Buckley, husband of the late Christine Buckley, whose ground-breaking letter to and interview with Gay in 1992 lifted the lid on the treatment of children in Ireland’s industrial schools.

There were many letters on other less serious topics — Ryder also found one correspondent who had a carbon copy of every letter he sent to Byrne over 25 years.

“There were so many days when we came across stories in letters that had us in tears or in knots laughing. Everything from people giving out about chickens being killed on Glenroe to those heartbreaking letters in the Gay Byrne Show Fund files. You could pick any letter from those files and find a story that resonates today.

“It is a social history of Ireland — but in the words of ordinary people. It was a real voyage of discovery. Gay had his finger on practically every social change that happened in the 25-year period that’s covered,” says Ryder.

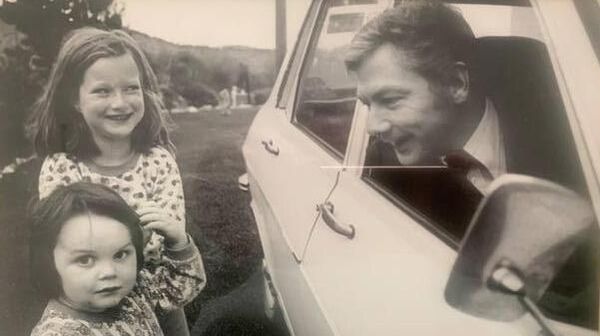

As well as Gay’s daughters, Suzy and Crona, another contributor to the documentary is Maura Connolly, the broadcaster’s personal assistant for 32 years. Among myriad responsibilities, she handled all his correspondence on The Late Late Show.

“I always had a policy of keeping Gay’s desk completely free of everything,” she says. “Thousands of letters would come in from people, often looking for tickets.” According to Connolly, whenever a controversial topic was aired on the show, postbags would bulge. Sometimes the resulting correspondence was unsavoury, to say the least.

“One of the most disgusting items was when time Gay demonstrated how to put on a condom, and someone anonymously sent in a used condom — Gay was disgusted by that,” she says.

“Sex, religion, politics, finance, we covered it all. I remember that we got terribly sad letters as a result of having Maura O’Dea on. She was an unmarried mother who kept her child. There was no help whatsoever for unmarried mothers at that time — you were either banished from your family or to a convent — you would lose your baby one way or another.

“If you came back into the community, your child was labelled for life and people didn’t want to employ the mothers. Maura O’Dea couldn’t get a flat and ended up in a mobile home in a field in the middle of Tallaght,” she says.

Byrne was also producer of The Late Late Show and was hands-on in every aspect of the show, says Connolly.

“Management frequently wanted him to go into an office on his own but he said, ‘No, I’m staying in the middle of the team’. He always believed we should say what we thought honestly, that it was constructive criticism. He said secrecy breeds suspicion, insecurity and was very bad for morale and the programme.

“As leader of the team, he would say what he thought if a researcher had given him a wrong designation for somebody, he would say ‘never let that happen again, I’m the patsy out there holding it all together and I don’t want to get things wrong’. If he didn’t deliver for us on an item, we would tell him that too. He didn’t hold grudges, no matter how much aggro came as a result of a programme, he just carried on.”

Connolly says that underpinning Byrne’s approach was his journalistic objectivity and a dedication to the truth.

“He was an extremely good journalist. Nobody knew what his religious or political views were. He was a safe pair of hands — he led without prejudice, he was a great listener, always compassionate, courteous, never rude, aggressive or adversarial, yet he drew people out. Whoever the guest was, whether it was the Rose of Tralee, the Late Late or the radio, they were the one to shine and he was the facilitator.”

Byrne was always aware of the team effort that enabled him to work at his best, says Connolly, and often gave verbal credits to staff during his shows, something she says was unusual.

“I remember when the Ireland team were doing very well under Jack Charlton, they came in and sang a song. They gave Gay a green Ireland sweater, and he wore it every day working on the Late Late. I would sneak it away and wash it every weekend to have it fresh, I was like his mammy. I gave it to him when he retired as well. We were all there to polish his star and he appreciated every one of us and every bit of work we did. The nation loved him, we loved him.”

The documentary shows how Byrne’s principles were at the core of everything he did, and that included listening to his audience, and reflecting their lives and concerns, says Ryder.

“At the heart of all of this is the character of Gay. He was someone of incredible integrity and a Christian in the true sense of the word, and we have tried to capture that in the documentary.

“When people started coming forward to tell their stories about Mother and Baby Homes or industrial schools, he believed getting the truth out was paramount. We all know the fallout from those interviews and those initial letters, and what happened since but he was the person that enabled people to tell their stories because in an Ireland when nobody else was listening, Gay was listening.”

- Dear Gay, RTÉ One, Wednesday, June 2, 9.35pm