It doesn’t ever feel like much of a coincidence for me that Father’s Day occurs during Pride Month. Though I suppose it is.

The first Father’s Day commemorations were around the turn of the last century. One in 1908 honored more than 300 men who had died in a coal mine in West Virginia. Two years later, a woman whose widower father raised her and her five siblings tried to make Father’s Day a national celebration, but it took until 1972 for that to actually happen.

Pride Month was inspired by the Stonewall riots of 1969 and has only received recognition from Democratic presidents, starting with Bill Clinton (though in 2019, President Donald Trump did tweet about it).

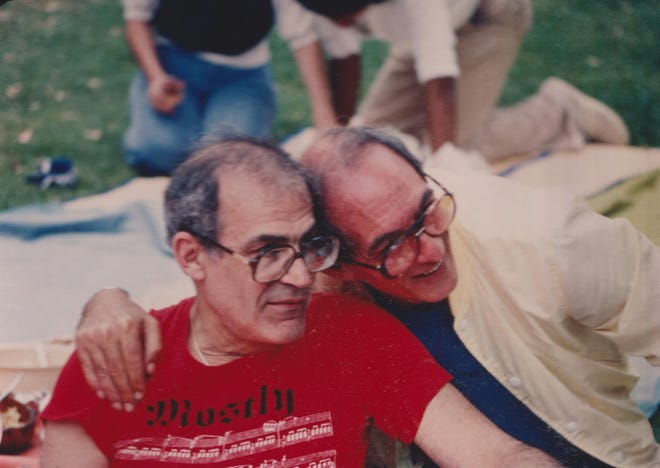

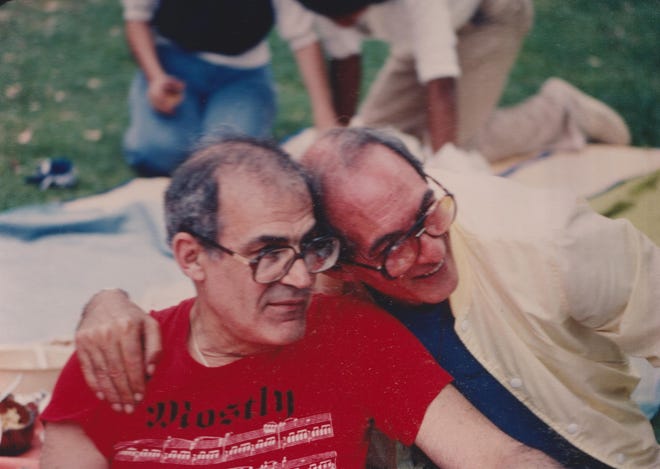

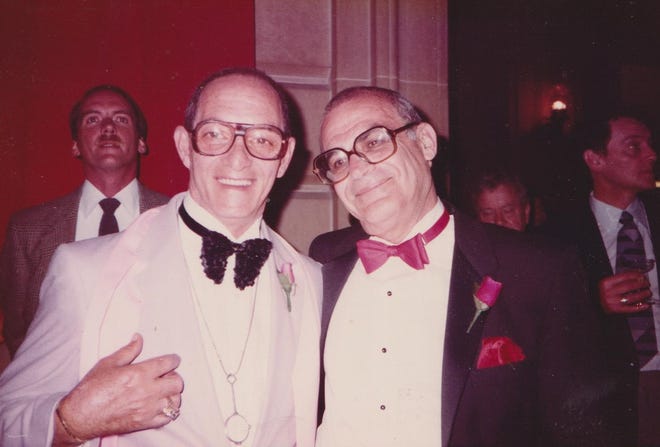

For me, though, the two celebrations have been inexorably linked for decades. In late 1980, at a support group for gay fathers, my dad met Lionel –– the man with whom he would spend the next 23 years.

The Father’s Day gift request I refused

A few months later, I helped them move into an apartment in West Hollywood. I was happy for my dad. He had seemed kind of lost in his new life – pushing 60, recently divorced from my mother, recently out of the closet as gay man. The indignities he had endured included requiring my assistance to get rid of an angry hustler, who was just a few years older than me, and defending him against the angry Orthodox Jewish parents of a young man with whom he had a brief, awkward romance.

The year after he met Lionel, 1981, was the only time my father ever asked me for a Father’s Day present. He asked that I march with him, alongside the other gay fathers and their kids, in the Los Angeles Pride Parade.

I don’t remember much about the parade. What I do remember was that someone had made T-shirts that said “I LOVE MY GAY DAD” and I refused to wear one.

I was 22 and in full possession of that youthful self-consciousness mixed with self-serving pseudo-idealism. I told my dad, “I love you, but not because you’re gay. I don’t love you in spite of it, either. I’m glad you got things straight with yourself and the world, but I’m not wearing a shirt that defines our relationship so simplistically.”

The truth, though, is that I lacked the courage to stand all the way up for my father and his comrades against a homophobic and indifferent world. My dad didn’t push me. He was glad I was there with him at all.

I probably left my “I LOVE MY GAY DAD” T-shirt next to the box it had come out of, though I might have taken it home with me and buried it in a drawer. What I do know is that I don’t have it anymore. And I wish I did.

Together but never allowed to marry

My father passed away a little over 10 years ago, after a decade of heartbreak and illness, a slow and quiet fade from the world. I dug out a lot of old photographs to show him in the last few years of his life to try to rouse him from his catatonic state.

Mostly, he just stared expressionless. Occasionally, he would reach out or his face would hint at a smile, like when I held up a photograph of a young soldier with whom he had served in World War II.

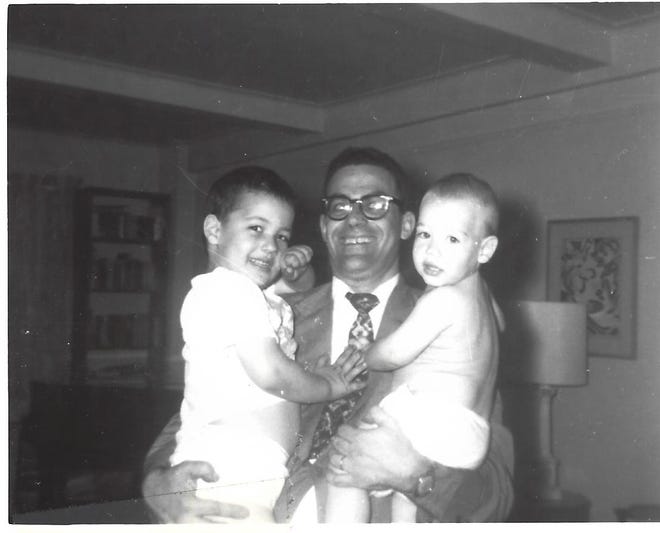

Mostly, the photographs roused me. Like the picture of him proudly holding my brother and me in his arms. The one that shows us carving pumpkins. And him standing in line outside New York’s Madison Square Garden for hours to get playoff Knicks tickets in the nose-bleed section for himself and me. Actually, that last picture is just one from my mind, along with thousands of other memories and images of him.

Lives depend on it:We need to celebrate LGBTQ joy this Pride Month

I had thought I might get a rise out of him with the photographs of him and Lionel getting arrested at a protest outside former California Gov. Pete Wilson’s office, or at the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights.

My dad and his husband lost a lot of friends to AIDS. Many had been abandoned by their families and had only their friends to take care of them – and then bury them.

Did I say husband?

Of course, John Strauss and Lionel Friedman were never married. Lionel passed away in 2003, five years before same-sex marriage first became legal in California in 2008.

I told my father when that happened. I thought he’d want to know – though I couldn’t tell at that time if anything I said registered.

I didn’t tell him when, later that year, the voters in this state banned same-sex marriage through a proposition. But I did tell him, just a few months before he died, that the California Supreme Court declared that proposition unconstitutional. And when he passed away and I was filing for his death certificate, I declared him a widower.

Whenever I meet a married couple of the same sex, I think of my father, and how he and Lionel, alongside their friends and peers, helped to break the road. I’m proud of his commitment to justice – for all people.

And I’m grateful for his love for and commitment to my brother and me. The man had no interest in basketball and didn’t even understand the game, but he took me to one of the most legendary games in basketball history. Actually, when Willis Reed hobbled out onto the court and we all stood up with a collective roar, and when Willis hit the first two shots, I don’t believe my father had any trouble understanding the transcendence we were witnessing.

Larry Strauss:My mother never gave up on my brother. Because of her, I never give up on my students.

Most of all, I’m grateful for my father’s patience with me.

For his ability to see only the good in me.

Even when I was an obnoxious 22-year-old and wouldn’t put on a T-shirt to declare, unashamed, unembarrassed and unapologetic, that I love my gay dad.

Larry Strauss is a high school English teacher and retired basketball coach in South Los Angeles. A member of USA TODAY’s Board of Contributors, he is the author of more than a dozen books, most recently “Students First and Other Lies: Straight Talk From a Veteran Teacher” and, on audio, “Now’s the Time” (narrated by Kim Fields). Follow him on Twitter: @LarryStrauss