With the coronavirus pandemic, James sees treatments slipping under the radar once again. While the federal government poured $18.5 billion into vaccine research, only about $8.2 billion went to treatments. One drug that has gotten a lot of attention, hydroxychloroquine, has largely proved to be a dud. Even though half of all American adults have received at least one vaccine dose, research on COVID-19 treatments remains vital; tens of thousands of Americans are still hospitalized with the coronavirus, and better treatments might help them. Meanwhile, for COVID-19 long-haulers dealing with lingering effects of the virus, treatments may offer the best hope of a return to normalcy. With COVIDSalon, James is leaning into a notion that he and other veterans of the AIDS epidemic helped trailblaze in the ’80s: Patients can become experts on their own disease, and that starts with supplying them with the right information.

When James launched ATN, the situation was dire. In 1985, 8,406 Americans died of AIDS, nearly doubling the number of deaths from the year before. But few drug trials for AIDS were under way, and those that were rarely received mainstream coverage. Because doctors didn’t know how to treat the new disease, people with AIDS needed to research their own symptoms and, sometimes, plot their own course of care. Activist groups such as ACT UP “really promoted the idea of Let’s get this [treatment] information out there,” says Patricia Siplon, an AIDS activist and a political-science professor at Saint Michael’s College, but few people had the time or the ability, before the internet, to do the research. With the queer community left in the dark about how to address the epidemic, James started accessing a dial-up computer database that hosted new treatment research as well as reports from the FDA and drug companies. Every two weeks, he would condense his findings into a two-page newsletter.

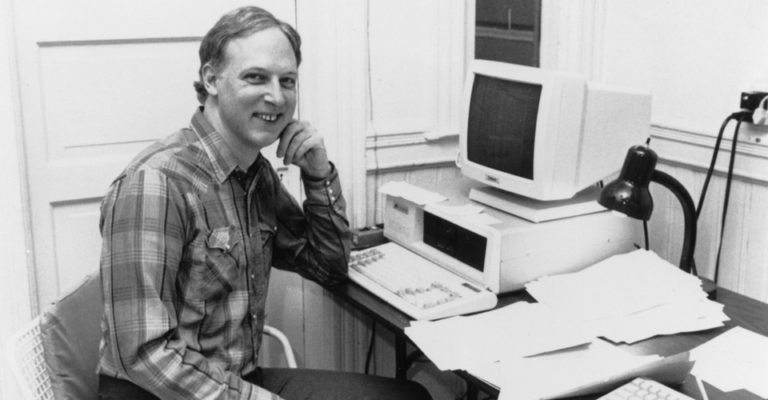

After his newsletter started getting traction, James turned his San Francisco apartment into a makeshift newsroom. He and an assistant made copies a few blocks away, and mailed them out to subscribers one by one. Volunteers edited, fact-checked, and produced the newsletter at all hours. “When I needed to get to sleep at night, if they were still working, I would put a piece of cardboard over my face to block the light,” James said. He broke major news stories, including one about a steroid hormone, and directed people with AIDS to research trials, in which they could enroll and access experimental drugs.

ATN became the go-to source for lots of people looking for treatment news: By the early 1990s, the newsletter had amassed more than 7,500 subscribers, including both people with AIDS and medical professionals, powered by a staff of five plus James. Even after the highly effective “AIDS cocktail” arrived in 1996, James turned his focus to the steep cost of the available drugs before finally shutting down the newsletter in the summer of 2007 to work on other research.