Sometimes being the first comes with fame and glory, sometimes it comes with pain. In the case of one former major league baseball player, being the first came with so much pain that no one remembers the things that should have brought him fame and glory.

That was the case for Glenn Burke, the first openly gay major-leaguer, who played for the Los Angeles Dodgers and Oakland A’s in the late 1970s. That was a first, but so were other things he accomplished that have been all but forgotten after homophobia chased Burke out of baseball after just four years.

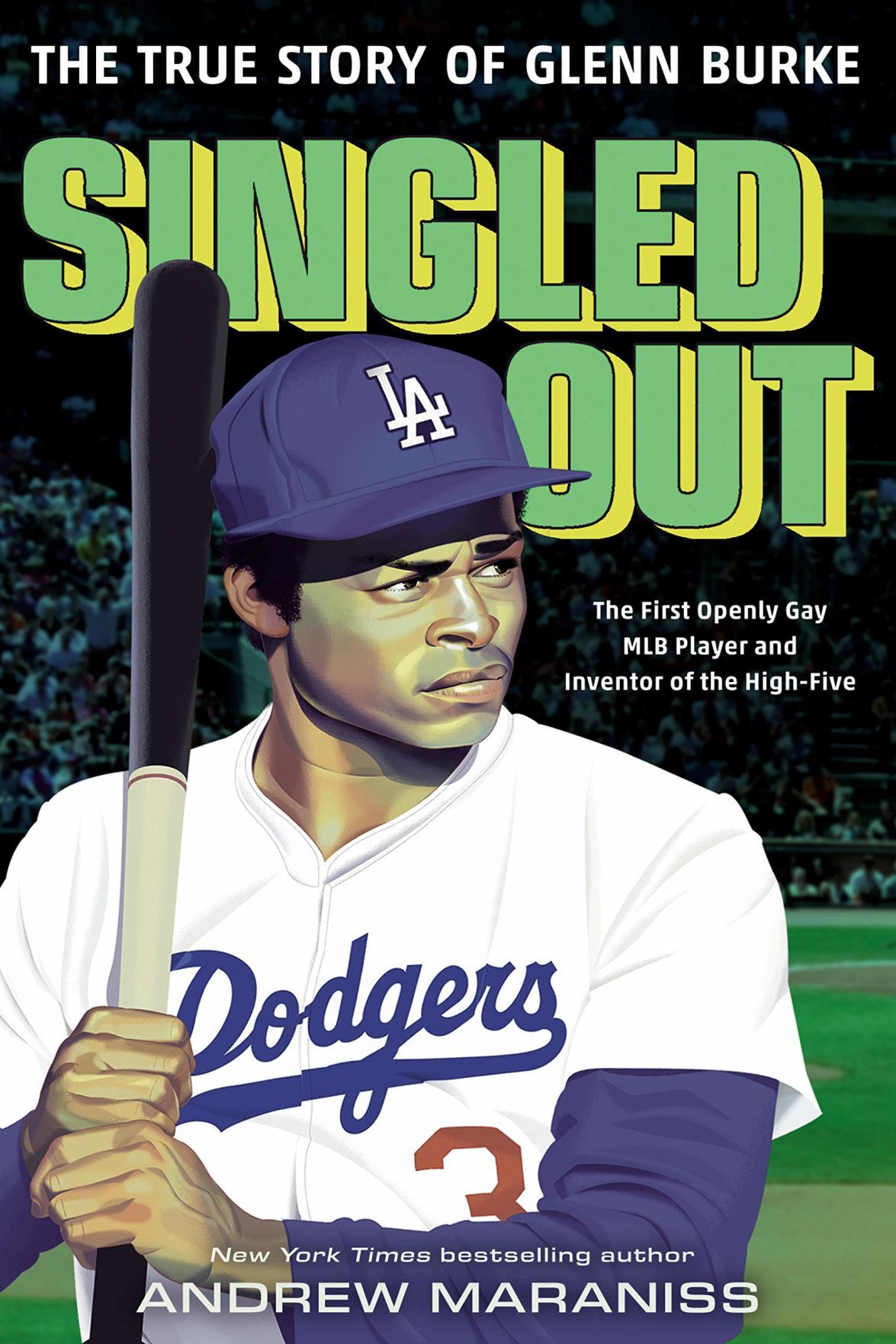

Andrew Maraniss is trying to change that with his new biography of Burke, “Singled Out.” Not only does Maraniss tell the story of how Burke’s homosexuality curtailed his professional sports career, but also the story of a colorful, popular athlete who is credited with inventing the high five and also was the first baseball player to wear a shoe from an up-and-coming shoe company called Nike. Burke died of AIDS in 1995 at age 42.

“There’s a new generation now that is ready to hear Glenn’s story,” said Maraniss, a Nashville-based writer who was born in Madison. “There have been strides made, so the story can be heard in a more empathetic way than it once was.”

Maraniss, son of Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist David Maraniss and grandson of former Capital Times editor Elliott Maraniss, has written two other books that explore the intersection of sports and social justice. “Strong Inside” told the story of Perry Wallace, who was the first Black basketball player in the Southeastern Conference and went on to become a professor of law. “Games of Deception,” which came out last year, told the story of the 1936 U.S. men’s Olympic basketball team amid the backdrop of the Berlin Games held in the shadow of Nazi Germany. “Singled Out” continues in that vein, with a subject that goes way beyond sports.

“It was a chance to write about the times, the gay rights movement, the backlash; that’s what was appealing to me,” he said.

Burke was a talented athlete, one who probably could have pursued a basketball career (and he did play college basketball despite being a pro baseball player, also a first). He came to terms with his sexuality as a minor-leaguer and while Burke didn’t come out publicly until his playing career was over, he didn’t make much of an effort to hide it from the Dodgers when he made it to the big leagues.

That’s not what brought him attention in the Dodgers’ dugout, however. Burke was funny, and the rookie brought a welcome light-hearted spirit to the veteran roster that was under pressure to deliver a World Series championship. One of those light-hearted moments endures today: As veteran Dusty Baker rounded third base after hitting his 30th home run of the season, Burke stood in the on-deck circle with his hand raised in the air instead of in position for a handshake. Baker followed Burke’s lead and slapped his hand, creating the first of what is now the ubiquitous high five.

Off the field, things weren’t so smooth. Burke was friends with the gay son of Dodgers Manager Tommy Lasorda, which didn’t sit well with the manager. Team President Al Campanis offered Burke a $75,000 bonus if he got married.

“You mean to a woman?” Burke replied.

Despite Burke’s promise and key role on a World Series champion, the Dodgers traded him to the A’s the next spring. It was even worse for him in Oakland, as manager Billy Martin would introduce Burke to other players using a gay slur and vowed he’d never allow a gay player on his team. After being sent to the minor leagues again, Burke quit baseball.

“Once they found out who he really was, the attitude was, ‘We don’t want you around because of who you are’ and that robbed Glenn of everything he wanted to do in his life,” said Maraniss, who had Burke’s baseball card when he was a kid. “Not only did it cost Glenn, it cost the rest of us the benefit of someone like him. He created new things and you wonder what would have been next for him.”

Burke never found his way after baseball. He developed a drug problem, served a prison sentence, lived on the streets of San Francisco and died in 1995. Maraniss spoke to dozens of Burke’s friends, family members, teammates and social workers to piece together his story. Beyond the baseball, “Singled Out” is also a gut-wrenching look at the toll the AIDS epidemic took on the gay community, particularly Burke’s post-baseball home of San Francisco.

No baseball player has come out as gay since Burke played in the 1970s, and while baseball is one of the most conservative sports, Maraniss thinks it could turn out differently for another player today.

“If the situation were right, the right city or the right management, this could be a really popular player now,” Maraniss says. “If a player came out now, he could have the best-selling jersey in the major leagues. You don’t need everyone to accept you, but a lot of people would. There’s a great chance that it would go much better now than it did for Glenn.”

Maraniss’ next book is about the 1976 U.S. Olympic women’s basketball team, the first year women’s basketball was an Olympic sport. The book coincides with the 50th anniversary of Title IX.