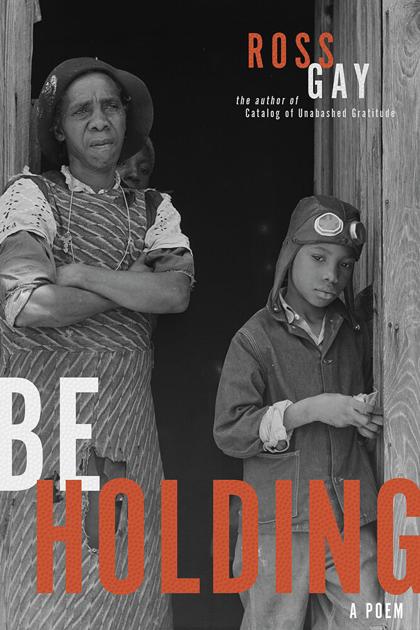

If you cherish words, stories or basketball, maybe you had best be holding Ross Gay’s book-length poem “Be Holding” — either in your lap or at the library’s website, https://mcpl.info.

Francine Prose, writer and critic, tells literature’s lovers to “read closely and slowly.” To return to the author’s phrases and punctuation choices as many times as necessary, to absorb their impact. To chew and grind, to taste every syllable-morsel.

This is how to take in Gay’s enormous sense of looking up. Looking up, as though from floating under water, seeing blurred faces. Looking up to see what we have missed seeing for ages.

Whenever I read someone like Gay, I enviously know I could never be a great writer. Looking up at this man’s writing is to think How did he see that? Gay can make someone love basketball, someone who hasn’t been in a sports arena in two decades. He can make you go out of your way to find that Youtube video — “in this move, which ostensibly occurred / in the 1980 NBA Finals” —of Dr. J (Julius Erving, one of the universes’s greatest basketball players) grabbing that basketball with one hand and “leaving his feet” and “turtling” his head back within one-half second of smashing it into the glass backboard.

And you almost cry, maybe you do cry, when that ball somersaults over “the rim (Dr. J) would, imminently, rock the rust from” into the “steel hole.” Even though two tall guards are practically jamming their fingers into Doc’s cheekbones.

“have you ever decided anything / in the air?” Gay asks.

You say, “Man, I’ve got to start watching sport again.”

And then, kind of like a baseline pass, Gay takes you off center, where you — you don’t want to, but you end up compelled to — Google something so horrible, “The Marlborough Street Fire,” that you wonder how you will ever master your sadness. Maybe your shouldn’t. And Gay tells you about that (probably white) photographer who probably encouraged little Tiare Jones, some time after the accident, to smile for his camera, so he could try to get a prize for his picture of her pointing to Diana Bryant, her head- and torso-ruined godmother. The opportunistic picture-taker was “doing his small job / adding his small work / his touch / to the museum.”

Like a good film, Gay’s poem weaves brightness with darkness, so that you can come up for breath after imagining Diana Bryant’s and Tiare Jones’ fall from that decayed fire escape, caught on film mid-fall, by a different photographer (he won a Pulitzer prize for it) and return to the wonder of Dr. J leaping ceiling-ward, listening no doubt to the crowd’s incredulousness. Doc’s done it again.

Fran Lebowitz told Spike Lee, in Netflix’ “Pretend It’s a City” documentary that she wouldn’t compare a great athlete to a great painter, in this case, Picasso. I take Lee’s side. A great athlete is a poem, a sculpture, a piece of human art.

I met Gay last month in a Zoom meeting for my Rotary club. He is self effacing and soft spoken. He is also funny.

“the oaks dappling the oldheads and their discourse / (the best line of verse I will ever write),” he writes. You imagine his eyes twinkling as he typed.

But maybe the most chilling part of Gay’s poem is what he writes about a group of predominantly white students on a visit to the museum where hang the “Fire Escape Collapse” and the “Marlborough Street Fire” photographs.

“(They were) checking their phones / mostly not noticing / their noticing / we’re noticing / and always have been / the black people falling forever / framed on the pristine white wall.”