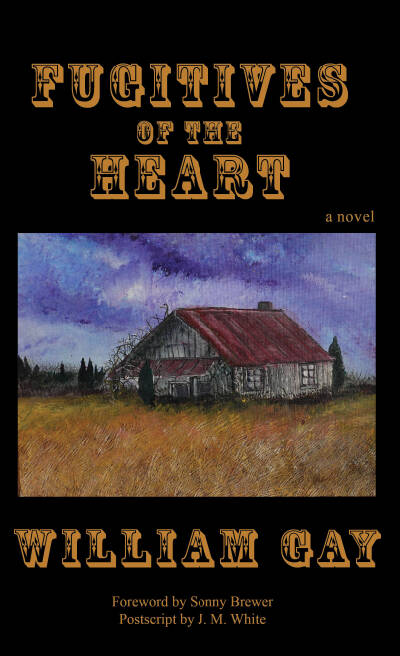

“FUGITIVES OF THE HEART” by William Gay (Livingston Press, 252 pages, $29).

Times are hard for the characters who populate William Gay’s “Fugitives of the Heart,” the last in a string of posthumous novels pieced together by his friends from an attic full of scenes Gay left behind. The writing in these fragments, as always with Gay’s work, was exquisite. For J.M. White, Sonny Brewer and the other writers who figured out how the scenes fit together, the effort was worth it, a forensic labor of love they feel even now for a writer who died in 2012. William Gay, they will tell you, was one of a kind; more precisely, he was a once-in-a-generation talent who could read the works of Mark Twain, William Faulkner or Cormac McCarthy, absorb what they were trying to do, then do it himself and make it his own.

“Fugitives of the Heart” is Gay’s homage to Twain. Yates, the protagonist, is just a boy when his daddy is killed, shot for stealing a side of meat from a neighbor in the hills of Tennessee. He’s Huck Finn in a different century, a boy of battered nobility and heart, hard around the edges and living off the land, whose only real friend is a Black man getting by on the margins of the segregated South. This is the rough South, the hills and hollows of Appalachia, where the Depression came early and never went away and people just do the best they can. Some of them, anyway. But maybe not Yates’ daddy, whose body is dumped from the back of a wagon by the man who caught him stealing from the smokehouse. The killer also leaves the side of meat: “If he wanted it bad enough to trade his life for it then it’s hisn.”

This is where the story begins, with a moment so cruel and unexpected that it is almost more than a boy can bear. But the mountains turn pretty in the spring — “a warm wind looping up from the south” — and Yates takes heart:

“He saw this early spring as a gift from the fates. A balancing of some cosmic scale. The scent of wildflower rode the winds, and he moved through this Edenic world with a newfound confidence. He began to think he might make it after all.”

In a postscript to “Fugitives of the Heart,” White writes about the first time he visited Gay and they were talking about Cormac McCarthy. Gay urged White to read McCarthy’s “Suttree,” and White reported that he was “blown away” — not only by McCarthy’s exquisite language, but by his ability, as White put it, “to make readers aware of events without ever describing them in the text.” It was an artful literary device that White could see in Gay’s own writing. When they talked about it, Gay smiled. The prototype, he told White, could be found in Faulkner’s “The Hamlet” — such had been Gay’s study of the craft, the literary art, that he detected in other writers and incorporated into his work.

He loved to talk about his favorites, almost to revel in his own admiration. His publisher, Joe Taylor of Livingston Press, recalls him as “one of the most humble writers I’d ever met,” and in “Fugitives of the Heart,” Gay lets his central character find words for his respect. Late in the novel, Yates, the boy, reflects on life with the Widow Paiton, an attractive neighbor who has taken him in, offering, in this cold and forbidding land, a warm place to stay:

“Nights by the fire she’d read to him Biblical tales. The stories of stern old prophets, their mad ravings She’d temper this with Twain, a chapter a night of Huckleberry Finn, Jim and Huck in a fix on the sunrimpled Mississippi.”

Ultimately, of course, “Fugitives of the Heart” is not “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” nor is it merely an echo set in another time. It is not as funny, for one thing. Its humor takes the form of irony, and while it is written in third person, not first, Gay has a gift for point of view, reflecting the world through the eyes of a ragamuffin boy, while still managing, as Twain did, to write in scenes that are lyrical and lovely — almost as if he were painting with words. But the portrait is dark. The interracial friendship at the heart of the story, which seems so promising at the start — flintier, perhaps, than the relationship between Jim and Huck, but a bulwark against a hard world — abruptly takes on the specter of betrayal. Redemption comes at a terrible cost, more in the form of authentic survival, and we are left with the unmistakable sense that this is the best Yates can hope for.

Or the rest of us, for that matter.

To read an uncut version of this review — and more local book coverage — visit Chapter16.org, an online publication of Humanities Tennessee.