This nation celebrates Pride Month every June to mark the anniversary of New York’s Stonewall riots, a seminal moment in LGBTQ history.

In 2020, the coronavirus pandemic shifted celebrations to a virtual platform. But this year, as COVID-19 restrictions are lifted and more Americans become vaccinated, some 2021 celebrations are back with a blend of virtual and in-person events.

Megan Springate says notable LGBTQ heritage sites are found across the country: “LGBTQ history is American history. It’s in every community.” People can visit these sites any time of year, not just for Pride.

Springate, a former National Park Service employee and now director of engagement at the America 250 Foundation. helped produce a study documenting hundreds of significant places and shared some favorites with USA TODAY.

Shop Pride:40 brands that are giving back for Pride Month 2021

Pride is back in 2021:Here’s how to celebrate with parades, in-person and online events

Stonewall National Monument, New York

A turning point in LGBTQ rights came in 1969, when New York police raided the Stonewall Inn gay bar and sparked street protests in the surrounding Greenwich Village neighborhood. “Stonewall was a real watershed moment,” Springate says. Today, it’s a National Monument, and visitors can get their National Park Service Passport stamped at the original bar. nps.gov/ston

First Unitarian Church of Denver

This 19th century building hosted one of the modern world’s first same-sex weddings in 1975 after a defiant county clerk issued a marriage license to a gay couple. But local officials refused to recognize the union until 2016. “Ultimately, their marriage was affirmed, and the government eventually apologized,” Springate says. fusden.org

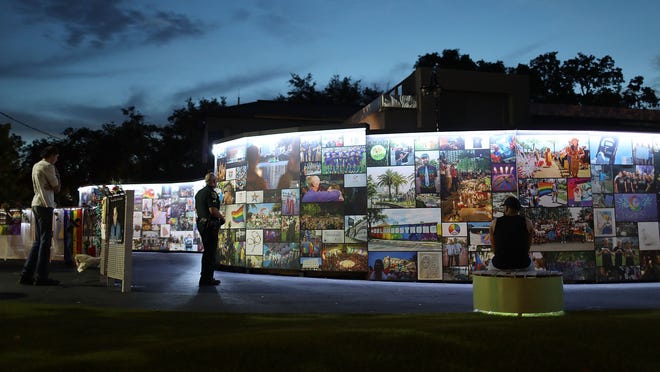

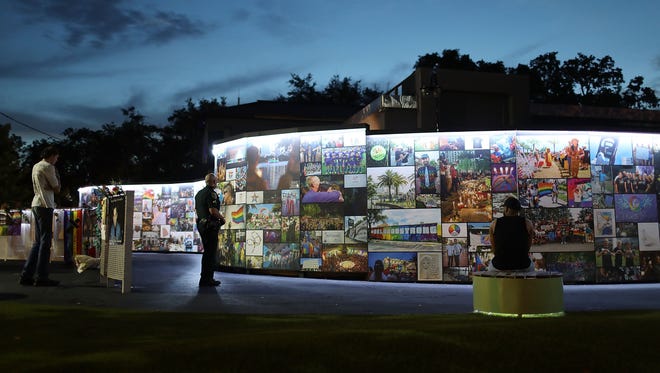

Pulse Interim Memorial, Orlando, Florida

Five years ago, the Pulse nightclub was the site of a mass shooting, considered the deadliest targeted murder in LGBTQ history, Springate says. Ultimately, the violence claimed 49 lives. The nightclub site now has an interim memorial, with plans to build a permanent monument and museum. onepulsefoundation.org

Independence National Historical Park, Philadelphia

In the years leading up to Stonewall, LGBTQ activists led protests in the historic district where the Declaration of Independence was signed. They held “annual reminder” July Fourth picketing demonstrations from 1965 to 1969 to publicize the inequalities they faced. “This was before Stonewall,” Springate says. After the Stonewall Uprising, protests changed. “It went from polite picketing to marching in the streets.” nps.gov/inde

Elks Athletic Club (Henry Clay Hotel), Louisville, Kentucky

For several years, this former downtown hotel housed the Beaux Arts Cocktail Lounge. Newspaper advertisements in the 1950s labeled the bar “gay,” which historians say was meant as a coded message for homosexual customers. “It was a straight-looking hotel bar, but gay men knew they could meet other gay men there,” Springate says. nps.gov/places/elks-athletic-club.htm

Congressional Cemetery, Washington

So many gay rights leaders are buried here that they’ve inspired a walking tour brochure. “It may be the only cemetery in the world with a special LGBTQ corner,” Springate says. Graves include Vietnam veteran Leonard Matlovich, who appeared on the cover of Time magazine. His tombstone reads: “When I was in the military, they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one.” congressionalcemetery.org

The Women’s Building, San Francisco

Founded by a women’s collective, this building still houses community organizations, from a food bank to a street youth group. It’s where a memorial service was held for Harvey Milk, the first openly gay member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, who was assassinated in 1978. “The whole community was able to find a space here,” Springate says. Another notable spot: Harvey Milk Plaza, where crowds gathered after his death. womensbuilding.org

Henry Gerber House, Chicago

Visitors can stop outside this private home where Henry Gerber, the “Grandfather of the American Gay Movement,” was once a tenant. In 1924, he founded the Society for Human Rights, recognized as the country’s first gay rights group. “It was a way for people to meet each other and realize that they weren’t alone,” Springate says. chicago.gov

Pauli Murray Family Home, Durham, North Carolina

Civil rights attorney Pauli Murray played a crucial role in shaping federal laws protecting women against employment discrimination. An African American who struggled throughout her life with her sexuality and gender identity, Murray helped found the National Organization for Women and advocated for both women’s rights and civil rights. “As a black queer person, this idea about equality was very personal for her,” Springate says. Her home is currently closed due to COVID-19, but an outdoor educational installation recounts Murray’s life and the history of the house. paulimurrayproject.org

Elizabeth Alice Austen House, Staten Island, New York

Acclaimed photographer Elizabeth Alice Austen shared this home (now a museum) with her partner, Gertrude Tate, for more than 50 years. While Austen’s photos at times showed subjects in gender-bending roles, her relationship has only recently gotten attention. “The connection between her personal identity and her work as an artist was missing. They have put that connection back,” Springate says. aliceausten.org