On Monday evening, a few hours after the Las Vegas Raiders defensive lineman Carl Nassib became the first active NFL player to come out as a gay man, Outsports, a website devoted to the intersection of sports and LGBTQ issues, contacted Dave Kopay for comment. Kopay obliged.

“Oh, shit!” he said. “That’s really big news. It’s fabulous. This is incredible.”

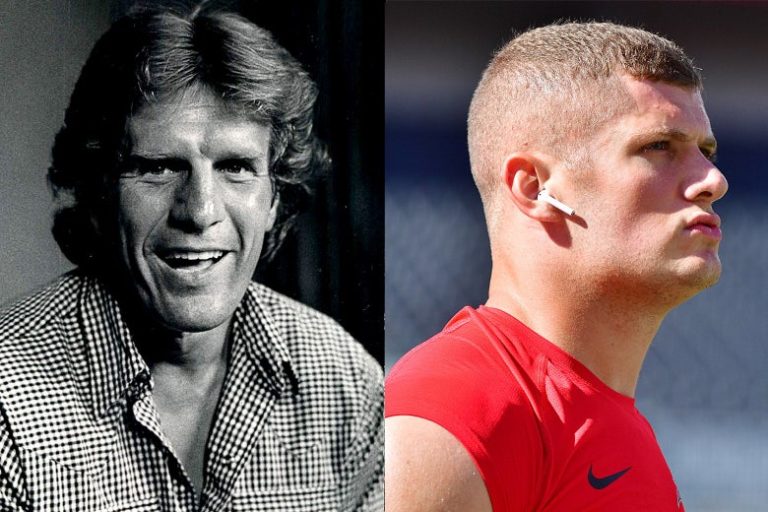

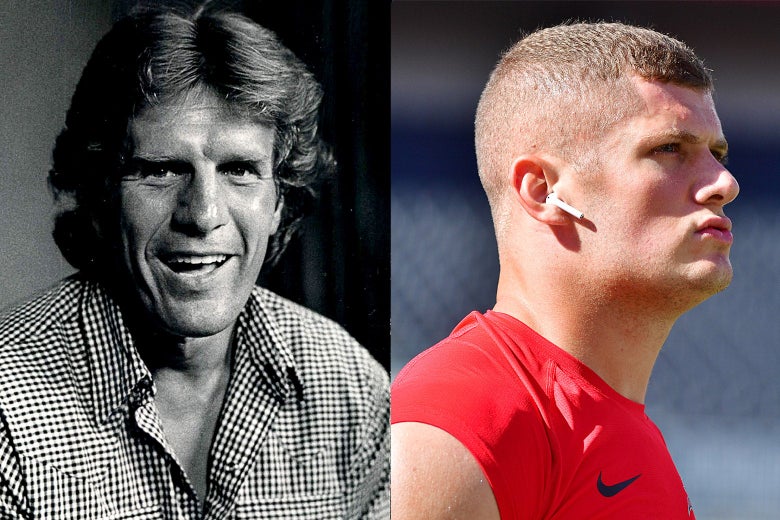

Kopay, who turns 79 next week, was a journeyman special-teams demon who eked out a nine-season career in the NFL. He is better known, however, for being the first ex-NFL player to come out, having revealed his sexuality to the Washington Star newspaper in 1975, after his playing days were over. Two years later, he further explicated his journey of sexual discovery in a memoir titled The David Kopay Story: An Extraordinary Self-Revelation.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

In the fall of 1997, I spent a convivial evening with Kopay at his apartment in West Hollywood. I was writing a profile of him for GQ. We watched Monday Night Football and discussed his experiences in the league and his curious latter-day status as a gay pioneer who nonetheless led a workaday life as a flooring salesman.

I was drawn to Kopay’s story because America at the time seemed to be experiencing a watershed moment vis-à-vis gay acceptance. Earlier that year, Ellen DeGeneres appeared on the cover of Time alongside the headline “Yep, I’m Gay,” eliciting a largely positive response. Three years before that, upon winning an Oscar for playing an AIDS-afflicted lawyer in Jonathan Demme’s Philadelphia, Tom Hanks delivered a tearful speech in which he sang the praises of his high-school drama coach, a gay man. At the awards shows and benefits of the era, lapels and bosoms were commonly adorned with a red ribbon, denoting its wearer’s solidarity with those who were suffering from and/or were fighting the good fight against HIV/AIDS.

Advertisement

Yet Kopay remained virtually alone in the football firmament, 20 years after his book’s publication—a source of no small degree of frustration. That evening and in our later phone conversations, Kopay sometimes flashed anger, referring to himself bitterly as “lonely old me, Dave Kopay–the-gay-football-player.” He still adored the game and harbored a desire to be associated with it, as a coach or a liaison to the gay community. But when I contacted Greg Aiello, then the NFL’s director of communications, about this possibility, he told me, “In general, the gay issue is not something that concerns us.”

Still, I suspected that it was only a matter of time before a pro football player would feel comfortable enough to come out, given the societal developments and Dennis Rodman’s gleeful experiments in public queerness. (This went beyond dressing in drag and wearing makeup; Rodman disclosed his sexuality in 1996, both in his best-selling memoir Bad as I Wanna Be and in a promotional appearance on The Oprah Winfrey Show .)

Advertisement

The worst thing a player can do in this culture is express his individuality in such a way as to become a “distraction” to the team.

While I was researching my Kopay article, I caught wind of a rumor that a then-current NFL player was on the cusp of identifying himself as a gay man to a major reporter at ESPN. I contacted the reporter, who confirmed that the scoop was imminent but would neither identify the player nor speak with me on the record. The negotiations were delicate, the reporter explained; a public acknowledgment of the very existence of the pending story might scupper the whole thing. In any event, something scuppered it—the story never made it to air.

So here we are now, 24 years after my hang with Kopay and 46 years after his initial disclosure to the Washington Star. In light of these astonishing gaps, “Oh, shit!” is a perfectly rational response. The Arizona Cardinals’ J.J. Watt tweeted his support for Nassib, adding, “Hopefully these types of announcements will no longer be considered breaking news.” But for the time being, Nassib’s announcement is a big deal—the long-overdue assignment of a face and name to a gay man enjoying a successful career in the NFL right now.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Why did this moment take so long to arrive? Institutionally, the NFL had already pivoted, overcoming the intransigence encapsulated by Aiello’s brush-off of my inquiry. In 2021, queer positivity is a given in the American sports-entertainment sphere. The league sponsored floats in the 2018 and 2019 New York City Pride Marches. For this year’s Pride Month, 10 of the NFL’s 32 teams have made over their Twitter logos in rainbow colors. The most cringe-inducing aspect of revisiting my GQ article is seeing how dismissive I was when Kopay suggested that the NFL Players Association should issue a statement in support of gay rights. Incredulous, I asked him what kind of occasion the NFLPA would ever have to put forth such a statement. “Doesn’t have to be an occasion—it’s what’s right,” he said. Kopay, needless to say, was entirely correct, and I was unreasonably skeptical. (For the record, the NFLPA and its executive director, DeMaurice Smith, tweeted their support for Nassib.)

Advertisement

But an individual player has a harder road to travel. The NFL remains the most hierarchical and militaristic of all the major U.S. sports leagues. Its resident coaching genius, Bill Belichick, grew up in Annapolis, the son of a Navy man who coached for the Midshipmen, the Naval Academy’s football team. The league dedicates three weeks of every season to a military-appreciation campaign known as Salute to Service, in which the teams’ coaching staffs roam the sidelines in NFL-issued camouflage and Army-green apparel. And for years, the Department of Defense paid the league millions of taxpayers’ dollars to promote the U.S. armed forces. Like the military, the league’s predominant culture has long been one that valorizes obedience to superiors and conformity over self-expression. The worst thing a player can do in this culture is express his individuality in such a way as to become a “distraction” to the team.

Advertisement

Advertisement

One former NFL player who can likely identify with Kopay’s sense of exile is Colin Kaepernick. The 49ers quarterback was upheld in his early playing years as an inspirational model of moxie, an adopted kid who emerged from a lesser college program and led his team to two consecutive NFC Championship appearances, reaching the Super Bowl once. That all changed in 2016, when he began his custom of kneeling during the national anthem as a silent protest against police brutality. Like Kopay, Kaepernick was effectively excommunicated from the league for not being a good soldier.

You can see why gay players were disincentivized from coming out. For the Kopay profile, I interviewed Leigh Steinberg, at the time the agent for the quarterbacks Troy Aikman, Warren Moon, and Steve Young. “If I ever had a client who was gay,” Steinberg said, “my advice would be never to discuss it unless he had a strong enough personality to handle it. Jackie Robinson, to do what he did, had to have such a Martin Luther King–Mohandas Gandhi, turn-the-other-cheek way about him.”

Advertisement

The false dawn represented by Michael Sam, an openly gay defensive end drafted by the St. Louis Rams in 2014, seems to bear out this harsh analysis. Sam’s selection prompted euphoric press coverage and personal congratulations from President Barack Obama, but he didn’t make the team’s final cut and never played a regular-season down in the NFL, citing mental health reasons for his choice to retire from football the following year.

Advertisement

Advertisement

However, the events of last summer, when demonstrators massed across the country to protest the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, marked an inflection point. Corporate America—the relatively enlightened segment of it, anyway—was compelled by public pressure to reckon with at least some of its past wrongs. For its part, the NFL last June committed $250 million to a social justice initiative to combat systemic racism, and commissioner Roger Goodell posted a video in which he declared, “We, the National Football League, admit we were wrong for not listening to NFL players earlier.”

Advertisement

It was a vindication of sorts for Kaepernick, if too late to save his playing career. But by the time an active football player chose to come out as gay, the league was no longer in a position in which it could keep mum or withhold its support. When Nassib nobly pledged $100,000 to the Trevor Project, the nonprofit devoted to suicide prevention among LGBTQ youth, the NFL promptly matched his donation.

Nassib, for his part, is a mild-mannered fellow, not the totemic figure of Steinberg’s imagining. The tone of his announcement, delivered via Instagram video, was almost offhand: “What’s up, people, I’m Carl Nassib […] I just wanted to take a quick moment to say that I’m gay. I’ve been meaning to do this for a while now, but I finally feel comfortable enough to get it off my chest.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

He’s an easy guy for the NFL to embrace: a sixth-year veteran, a clean-cut white dude. We don’t yet know if Nassib’s actions will precipitate a dam-burst, a wave of out queerness on the gridiron in all its pan-spectral glory. But if nothing else, it’s about damned time that, nearly 50 years after his pro-football career ended, the league has finally caught up to Dave Kopay.

Listen to an episode of Slate’s sports podcast Hang Up and Listen below, or subscribe to the show on Apple Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts.