For Eric Sawyer, the 40th anniversary of the first scientific report that described AIDS as a new disease brings up “a dichotomy of feelings.”

When Sawyer, who was living in New York, first began exhibiting symptoms of HIV in 1981, he said he was urged by his friend, the late activist and playwright Larry Kramer, to begin seeing “a doctor who’s also gay, who is seeing patients with this disease.”

That same year, across the country, a young physician named Michael Gottlieb and his colleagues at UCLA wrote in an official Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report about patients diagnosed with a lung infection common in what would come to be called AIDS.

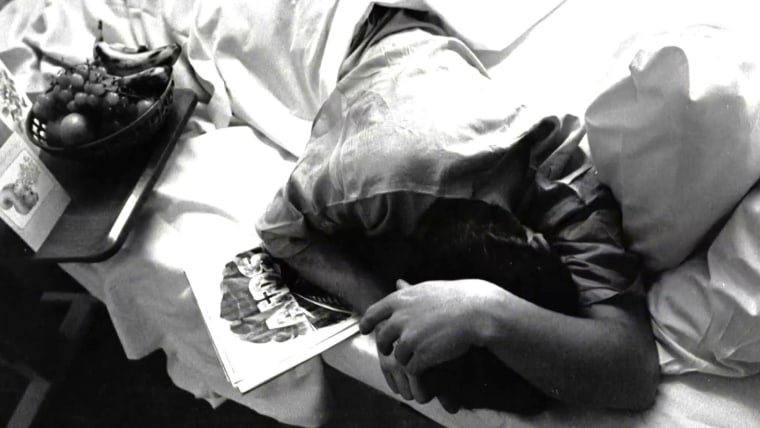

“In the period October 1980-May 1981, 5 young men, all active homosexuals, were treated for biopsy-confirmed Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia at 3 different hospitals in Los Angeles, California. Two of the patients died,” the report, published on June 5, 1981, in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, stated.

Sawyer, now 67, recalled being told by a doctor, at just 32, to put his affairs in order.

“In addition to being elated that I have survived for 40 years with this illness, I also have a certain degree of survivor’s guilt,” Sawyer, a founding member of AIDS activist group ACT UP New York, told NBC News. “Why me? Why did I deserve to survive when so many of my friends and a couple of my boyfriends died really horrible, ugly deaths at very young ages?”

Four decades after the CDC published the now-historic report, long-term survivors like Sawyer, as well as HIV/AIDS activists and doctors, are reflecting on their experiences on the front lines of the crisis and warning of the inequities that have allowed it — which has killed an estimated 34.7 million people globally since the epidemic began, according to UNAIDS — to persist.

“AIDS in the United States is not over, and especially it’s not over in the Global South or around the world,” said Jawanza James Williams, the director of organizing at VOCAL-NY, a nonprofit that helps low-income people impacted by HIV and AIDS. “There’s a sort of tendency to talk in the past tense, as if HIV and AIDS, as an epidemic, has been ended in the States, and it erases the realities and the experiences of Black people, of brown people, or poor people, people that are uninsured, and it really misses the mark.”

People of color are disproportionately impacted by HIV, according to the CDC. Of new HIV diagnoses in the U.S. in 2018, Black Americans accounted for 42 percent and Latinos accounted for 27 percent.

‘Something clicked’

Gottlieb’s encounters with the patients he would end up documenting in his June 5, 1981, CDC report started with one gay man “whose immune system was kind of totaled by something.” Then, within a month, there were three patients just like the first, he recalled. They were all between the ages of 29 and 36.

“Something clicked. There’s something going on that is very unusual and needs to be reported to someone,” said Gottlieb, now an HIV and internal medicine specialist at Los Angeles-based APLA Health, a network of Federally Qualified Health Centers that serve LGBTQ people and people impacted by HIV.

While the CDC uses the date of the report to mark the start of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, “that’s not factually correct,” Gottlieb said.

Prior to 1981, evidence suggests that Robert Rayford, a 15 year-old boy, died in St. Louis in 1969 from a condition later identified as AIDS.

Later in the 1970s, there were accounts of individuals becoming sick with parasites or what was then called “Gay bowel disease,” “and it probably was HIV, but we didn’t know it,” Dr. Howard Grossman, a primary care physician specializing in HIV treatment and prevention, told NBC News.

For activists and survivors, the history of the HIV crisis transcends a linear timeline that can forget the nuance of human experience, according to Ted Kerr, a writer and organizer whose work focuses on HIV/AIDS.

“My No. 1 fear is that people will think that HIV started 40 years ago, and what that does is it suggests that HIV begins when the United States government says it begins,” Kerr said. “Actually for me, it begins when someone’s journey with HIV starts. So, the history of HIV starts tomorrow for somebody when they get their HIV diagnosis. HIV started in 1969 for the Rayford family in St. Louis when Robert died, and, of course, that also includes the June 5 article from the CDC.”

‘New homosexual disorder’

As a gay man in medical school in New York in the early 1980s, Grossman, now the medical director of Midway Specialty Care Center in Wilton Manors, Florida, said the first stories he heard of people getting what would eventually be known as AIDS were imbued with “judgment” about drug use and promiscuity.

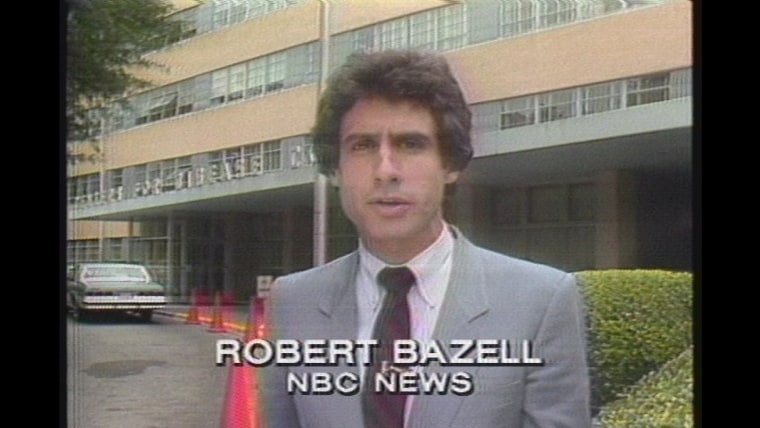

In an article from May 1982, The New York Times referred to the disease as a “new homosexual disorder.” A month later, in NBC News’ first report on the mysterious illness, “Nightly News” anchor Tom Brokaw reported that a new study found “the lifestyles of some male homosexuals has triggered an epidemic of a rare form of cancer.”

When Grossman attended a packed meeting convened by Larry Kramer and the newly formed Gay Men’s Health Crisis in 1983, “that was when people realized something really bad was going on,” he said.

As a medical resident in a Brooklyn hospital that same year — when much of the public still thought this mysterious illness primarily affected gay men — Grossman saw intravenous drug users, people of Caribbean descent and women who, in retrospect, he believes were exhibiting symptoms of AIDS.

Less than a decade later, Ivy Kwan Arce, a long-term survivor of AIDS and an ACT UP member, said she encountered disbelief when she asked her doctor for an HIV test after seeing an ACT UP poster that said, “Women don’t get AIDS. … They just die from it,” with fine print recommending that women with multiple sexual partners or who are drug users get tested.

After Kwan tested positive, she had to retest because the attitude was that “maybe the test was wrong.” She ended up at an ACT UP meeting at The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center.

At the time, the CDC’s definition of AIDS excluded medical conditions experienced by women who were later known to have the disease, causing the government to undercount the number of women who had died due to AIDS-related complications. Kwan participated in activism that pushed the government to expand the definition of AIDS to include specific conditions for women, alongside Katrina Haslip, an HIV/AIDS activist and fellow ACT UP member who died in 1992 from complications of AIDS, according to a New York Times obituary.

Kwan had been working as a graphic designer, but when her workplace found out she was HIV positive, she said they announced her diagnosis to her co-workers, forbade her from using the bathroom and asked for a calendar of her menstrual cycle before she was eventually fired.

More than 30 years after her diagnosis, Kwan said, the narrative for women living with HIV/AIDS “has not changed a whole lot.”

Jawanza James Williams, who was diagnosed with HIV at 23, said various communities that were responding to the crisis early on have been erased from AIDS history.

“It suggests that somehow Black folks, brown folks, women, trans people weren’t on from day one, responding with love to this crisis and still are,” he said.

Looking back to move forward

When Williams was diagnosed with HIV in 2013, he said he thought about the more than 30 years that had lapsed since President Ronald Reagan first publicly said the word “AIDS” in 1985. By the end of that year, the U.S. had more than 16,000 reported cases of the then-fatal illness.

For Williams, his diagnosis was also a moment of realization.

“It wasn’t some unique sexual behavior,” Williams, now 31, said of why he contracted the virus. Instead, he said he realized it was because of systemic reasons — such as race, location and class — and his close proximity to communities that are disproportionately impacted by HIV/AIDS.

While there is currently an effective HIV-prevention drug available for those at risk of contracting HIV, and a pill with few side effects that can treat those who are already living with the virus, Sawyer does not want the public to overlook the hundreds of thousands of people around the globe who contract HIV and die from AIDS-related complications annually. In 2020, an estimated 1.5 million people became newly infected with HIV, and 690,000 people died from AIDS-related illnesses, according to global statistics from UNAIDS.

“That’s far too many people dying and far too many people getting infected with what is a fatal disease if you don’t get access to the latest medical interventions and the latest medications,” said Sawyer, a co-founder of Housing Works, an organization working to end the dual crisis of homelessness and AIDS.

For Sawyer, the 40th anniversary of the historic June 5, 1981, report is a moment to recognize the lessons that “AIDS should have taught us.”

“It’s time we start caring about the health of everyone on this planet,” he said.