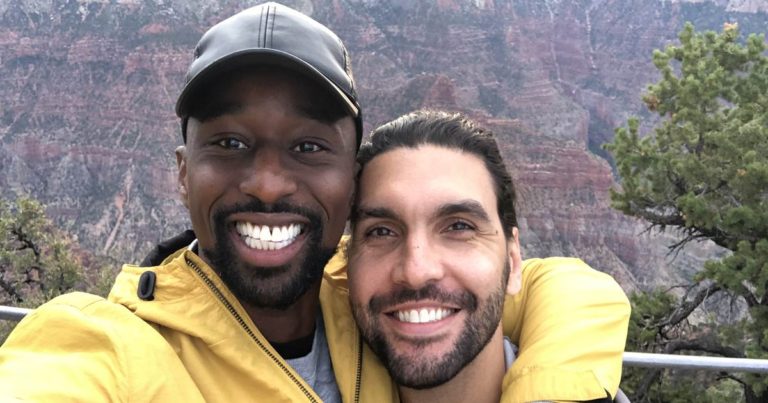

Chicago couple Adam Motz and Amadou “Tee” Lam have been together for more than five years. But they started talking about having kids on their second date.

“We were out to dinner and Tee brought it up,” Motz, 32, said. “Because for him — for both of us — having children was essential, and agreeing on that was the bare minimum before we could go any further.”

It was early to have the conversation, he admitted, “but we knew it wouldn’t work if we didn’t both feel the same way.”

Fortunately they did.

Motz and Lam, 38, were married last March. By the time the two men came back from their honeymoon, they were talking to potential egg donors. In June, they called a fertility specialist to discuss in vitro fertilization.

“When straight couples can’t conceive, we try to help. We deserve the same chance to build our family.”

Adam Motz

She warned them that, as a gay male couple, they might face pushback from their insurance company. Motz, a lawyer with the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office, is covered by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois. Like most carriers, BCBSIL doesn’t cover surrogacy. But Motz said when he called the company in July, an agent told him that the egg donation and fertilization would be covered.

“Then he called back almost immediately and said it wouldn’t be,” Motz recalled. “The reason he gave was because we were a male-male couple.”

Insurance mandates nationwide define infertility in heterosexual terms: Couples must try to conceive through sexual intercourse for a year before being covered. In most states, a woman without a male partner is mandated to attempt intrauterine insemination up to a dozen times before a plan covers egg donation.

But for Motz and Lam, their lack of a viable egg isn’t viewed by the insurance industry — or the law — as a medical problem. As a result, they had to pay close to $20,000 out of pocket for egg retrieval and prescriptions for their donor.

“We submitted the claims in October anyway,” Motz said. “Then, in November, a different agent left us a voicemail.” In that message, which Motz shared with NBC News, a BCBSIL representative states, “These services are not covered for male-to-male relationships, therefore they are being denied.”

Dr. Mary Wood Molo of Chicago’s Center for Reproductive Health told NBC Chicago she has seen insurance providers cover egg donor costs for patients of other sexual orientations.

“For hetero and lesbian couples, yes, but not for same-sex male couples — with any [kind of] insurance,” Wood Molo said.

Motz and Lam appealed the denial, with Wood Molo writing a letter they said BCBSIL requested, explaining why these two men could not become pregnant on their own.

“It was very obvious that Adam and I cannot have kids,” Lam said. “I mean, I don’t know how much more obvious it could be.”

Since then, the couple said, BCBSIL has changed its story several times. Initially, according to Motz, it claimed the egg donor’s prescriptions, which ran into the thousands of dollars, should have been covered by Motz’s prescription carrier. It then, Motz said, told the couple those claims were denied because the donor, Motz’s high school friend, wasn’t on his policy. Then in September, in a letter shared with NBC News, the insurer said the denial of these costs was a mistake and the claims “should have been paid.”

“They’ve changed the rationale for denying coverage so many times,” Lam said. “We’ve heard so many different excuses. But the consistent message is that it’s because we’re a male-male couple.”

That’s when the company is actually talking to them: Lam said BCBSIL stopped communicating for months on end, only re-establishing contact after NBC Chicago ran its story on their situation.

In a statement to NBC News, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois said it was committed to providing quality, cost-effective health care regardless of sexual orientation. “BCBSIL has a longstanding history and unwavering commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion across our company and in the communities we serve.” The company also has a page on its website about “LGBTQ inclusion,” where it states, “We work together with our lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning/queer (LGBTQ) employees to better understand the health care needs of our LGBTQ members.”

It has agreed to cover approximately $2,000 in expenses relating to the egg-retrieval procedure, but Motz and Lam say they are still out $18,000 from their initial claims. By the time their surrogate gives birth, the medical expenses alone could reach $60,000. The couple’s situation is not uncommon, according to Victoria Ferrara, a Connecticut attorney specializing in assisted reproductive technology law.

“The problem is with how insurance companies define infertility,” Ferrara, who also runs a surrogacy agency, said. “You have to be trying to get pregnant for a year before they’ll cover you. Obviously, for a gay couple, that definition isn’t going to work.”

Most insurance plans don’t cover surrogates and many don’t cover egg donors. Because they have to work with both, gay men face the highest financial burden when it comes to creating a family. But lesbians and single people also run afoul of insurance mandates centered on heterosexual couples.

In 2013, California passed legislation guaranteeing LGBTQ people coverage for fertility treatments — but not IVF, which male couples inherently require. New Jersey and a few other states have similar laws.

Nationwide “it’s a real hodge-podge,” Ferrara said.

New York’s Fair Access to Fertility Treatment Act, which went into effect Jan. 1, requires insurance plans serving 100 or more employees to cover IVF. But same-sex male couples aren’t included in that mandate.

“It’s so expensive for LGBTQ couples to have kids to begin with, that this smacks of not just plain discrimination but exacerbated discrimination,” Ferrara said.

Cathy Sakimura, family law director for the National Center for Lesbian Rights, helped draft California’s LGBTQ-inclusive fertility legislation. She said there needs to be a change in how we view helping people start a family.

“The language we use treats the situation like it’s an illness. In some cases, it’s just the physical circumstances of your body,” Sakimura told NBC News. “Why do we even call it ‘infertility’? It’s about fertility, about family coordination, about assisted reproduction.”

Reproductive justice, she said, is the ability to have or not have children in a way that makes sense for your family. She and other fertility advocates want egg and sperm donation, embryo transfer and, ultimately, surrogacy fees added to coverage plans.

It won’t be an easy battle: When advocates in California tried to pass a fertility preservation bill — which would have required carriers to cover egg and sperm freezing for people undergoing chemotherapy and other procedures — insurance lobbyists fought it so vigorously the measure was dropped.

“They’re going to fight really hard against this,” Rich Vaughn, founding partner of L.A.-based International Fertility Law Group, said. “It’ll take a lot of work to get this done in all 50 states.”

Vaughn said many of his clients inquire about coverage for fertility treatments and are turned down. “So the question becomes, ‘Do we fight the insurance company or do we just move on and start our family?’” he said. “Most just move on.”

Motz and Lam aren’t ready to give up just yet.

They’ve been in contact with the American Civil Liberties Union and are also working with a private attorney, not just for reimbursement of their claims but also on a possible discrimination suit.

“As a society, we’ve established that having a family is a priority,” Motz said. “If we really believe that, there’s no reason we should be deprived of the opportunity. When straight couples can’t conceive, we try to help. We deserve the same chance to build our family.”