The story of Bob Damron’s The Address Book begins, like so many others, with one guy and a full tank of gas cutting down the California coast. Picture him pulling out of the Castro in San Francisco, a notebook seated next to him, sun glinting off the rims of a wood-paneled station wagon. Maybe he didn’t drive that exact car, Gina Gatta concedes, but you get the gist.

Gatta owns Damron Company, the travel business that grew from Damron’s Address Book. “Like a Bible salesman, Bob would get on the road,” says Gatta. “He would travel around, and he would find the gays, and he would find the bars and bathhouses.”

In its earliest incarnation, The Address Book was gay equivalent of The Green Book, which shepherded African American travelers across the segregated South starting in 1936, and was recently highlighted in last year’s Oscar-winning movie of the same name.

Damron’s largely forgotten pocket-sized guide shaped queer America, long before Yelp, dating apps, or LGBTQ community centers. “It developed gay communities,” Gatta says. She credits the book with shaping Chicago’s iconic gay Halsted Street and the Castro in San Francisco.

Other LGBTQ directories sprung up during the early ’60s. The Lavender Baedeker started in 1963, but didn’t have the same longevity. David Johnson, LGBTQ historian and author of Buying Gay: How Physique Entrepreneurs Sparked a Movement, believes Damron’s survived, in part, because unlike other publishers, Damron never published gay men’s physique magazines that came onto newsstands in the early 1950s. “They were all prosecuted for obscenity and they were all essentially railroaded out of the business by the post office,” Johnson says. “Their businesses were destroyed.”

The impact of those early guides, including The Address Book, on queer America was profound, says Johnson.

“I think they helped knit the community together in a national way,” he says. “So it’s no longer just, you go to your local bar, but wherever you are, if you’re traveling to a big city from a small town, you can find the community.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/BJys6t7B5Lr/

For 45 years The Address Book, later renamed Damron Men’s Travel Guide, steered LGBTQ people from coast to cocktail lounge. It started before you could kiss on the beach on your Los Angeles vacation. In 1965, gay sex was a crime everywhere but Illinois. The Stonewall uprising, a turning point in modern gay history, was still four years away.

Damron’s pastel book told you where in Allentown, Pennsylvania, you could get a beer without getting being beat up. If you lived in Covington, Kentucky, you’d learn that Joche Bo’s was a good a weekend-only spot. In Los Angeles alone, you’d find more than a dozen bars and bathhouses.

Bob Damron personally checked in to 200 cities and 37 states during the first year of its two printings. “He would go back around to those businesses,” Gatta explains. “[He would] go to Joe’s bar and say, ‘here are your books, what’s new?’ And then you find out that there were five other bars. You go to the five of the bars, compile that, come back to San Francisco, put it back together, go back out again.”

Readers wrote and phoned in additional listings which were vetted and added to the book. Many were later removed after the book fell into the hands of police who started raiding the businesses listed. Damron’s own 1965 copy, which Gatta owns, still has blue pen marks with businesses scratched out, bars that had to be taken out after police crackdowns made them unsafe for LGBTQ travelers.

There are no mentions of gay life in the early books. Missing are images of shirtless men that floods gay literature from that time. The listings don’t even include descriptions, just addresses. The first listing in the book is in Birmingham, Alabama: “Fire Pit * 1915 5th Av N.”

Only a most discerning reader would gather that it was targeted toward gay men. A key at the start of the book offers a few more details about what one might find, but even those are sparse. “C” means a place serves coffee. An asterisk notes that a spot is particularly popular. “M” tells the readers the crowd is “mixed and/or tourists.”

“Bob Damron’s Address Book never said ‘gay’ due to fear of being outed,” Gatta explains. “Our clientele appreciated the secret title.” It wasn’t until 1999 that the company printed the word “gay” on its cover.

Despite the parallels between the Address and the Green Book, Damron didn’t empathize with people of color or women, says Gatta. “I believe he was a very prejudiced man,” she says. “I don’t think he liked people of color. And I know he didn’t like dykes. He’d be rolling over in his grave right now if he knew I was running this company.”

Things changed after 1985, when Damron sold the company to Dan Delbex, who was friend’s with Gatta’s gay brothers. Gatta frequented the Damron offices in San Francisco, and by 1989, Gatta found herself employed full time at Damron.

The 1980s were a time of rapid expansion and loss for the company as the AIDS crisis decimated a generation of men and the Damron catalogue exploded in popularity. The company expanded its offerings, publishing a women’s guide, The Gayellow Pages Damron City Guide, Damron Accommodations Guide, queer city reviews, and a range of international books.

In the 1990s, Damron’s phone bills totaled $2,000 a month, in part because Gatta and staff were calling listings to verify their existence as readers wrote in to add to the book. But they were also getting a flood of calls to their 800 number, people who were lonely or in trouble, people who couldn’t come out. Gatta began adding listings for LGBTQ organizations, AA chapters, and AIDS testing facilities. Bob Damron died in 1991 from complications of HIV.

Today, little remains of the gay world he chartered in 1965. None of West Hollywood’s bustling gay bars date back to Damron’s early days. Annex West, a spot that used to sit on Melrose, is now a Floyd’s Barbershop. Carnival Room on Santa Monica is now home to a gift shop. The front of the Explorer in Silver Lake has been painted over with the words “JESUS SAVES” in bright blue letters.

The Frolic Room in Hollywood is among the last remaining bars on Damron’s original list, but Robert Nunley, who has owned it for 37 years, says he has never heard it was a spot for LGBTQ people.

“I never considered it a gay bar,” he said. “It’s for everyone that wants to come. There’s gay people coming in, straight, lesbian. Everybody comes in. Everyone gets along.”

Even the Damron office is dated, a relic of the mid-1990s with an aggressive amount of furniture and computers that look like they haven’t turned on since since the days of dial-up internet. Gatta points out a typewriter in the corner. The carpet was probably three shades greener 30 years ago.

In the guide’s heyday, Damron execs toured the world, watched the books come hot off the presses in China. Today, Gatta shares the office with a psychologist part-time to help pay the rent. She’s the last the employee left, and she’s not even full-time. She consults on the side.

It’s hard to keep a print book going in the age of the internet. The Damron website doesn’t get a lot of traffic because its listings are buried behind a paywall. A younger LGBTQ generation, one that grew up with Facebook and Grindr, has likely never heard of The Address Book or the Damron Guides.

“People that grew up in urban cities did not need my book,” admits Gatta “You are already comfortable being gay. It was safe for you to be gay. You didn’t need to go find a safe place.”

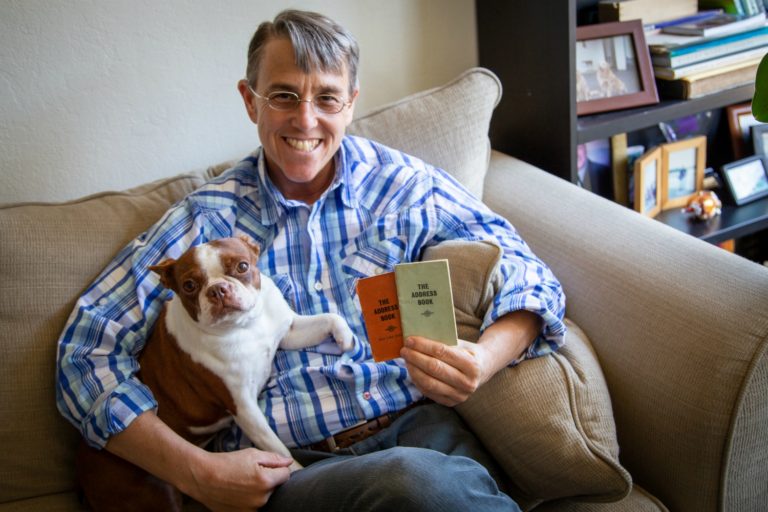

Gatta pulls out the 52nd edition of the guide. “I can’t see how I can do another one,” she concedes. She still has readers in red states, mostly older men. The women’s guide stopped publishing in 2016. It was never profitable.

She chose black for the cover of this year’s guide, not because it’s funerary, although one can’t help but make the connection. “The best quote I ever got was from The New York Times,” she says. “It was called ‘The Little Black Book of Gay Travel.’ So I chose black, in case it was the last one.”

RELATED: 100-Plus LGBTQ Icons and Iconoclasts Who Are Shaping Culture in L.A. and Beyond

Stay on top of the latest in L.A. food and culture. Sign up for our newsletters today.