Author and illustrator John Paul Brammer knew he had hit a professional low when was he living in New York City and recapping gay porn for a living.

Fired from a short-lived job working for a start-up, he found himself on “the smut circuit” — his words — feeling like a failed journalist. He was sleeping a lot, having panic attacks and drinking mimosas in the middle of the day. One morning, while staring at some graphic content awaiting his attention, a chilling thought hit him: “Oh God, my abuela picked fruit in this country for me to become this.”

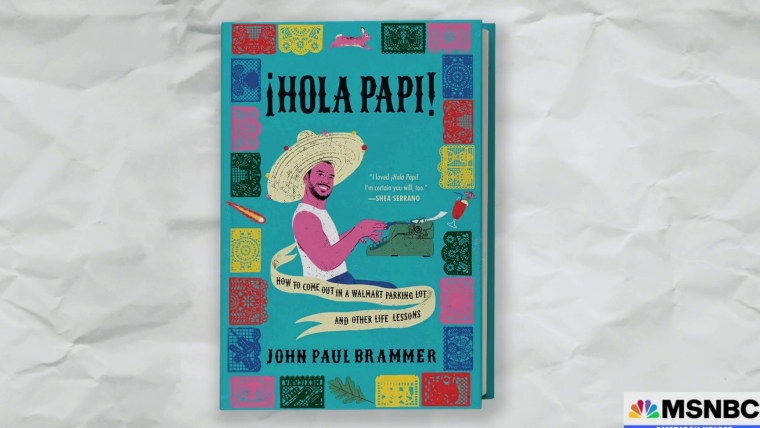

Such is the humor and pathos in Brammer’s first book, “Hola Papi: How to Come Out in a Walmart Parking Lot and Other Life Lessons,” which is out on June 8. A popular online advice columnist, Brammer weaves together his experiences growing up biracial and closeted in rural Oklahoma with letters he has received from readers asking about relationships, identity and love.

Brammer, 30 and “very single — make sure you put that in,” he instructed, originally began his advice column on the gay dating app Grindr. “Total strangers often sent me messages that began with Hola Papi, so I thought that would be a good name for the column; I intended it to be a spoof, as satire,” he said.

Papi, which means father in Spanish, is also used casually as a term of endearment to refer to a guy. “Then I began getting letters that were more serious,” Brammer said, “and I realized I had a responsibility to take them, and my role, more seriously.”

Brammer’s column then moved to Them, and later Out Magazine, and it can currently be viewed at The Cut and on Substack.

One of the most common themes Brammer sees in emails from readers is loneliness, whether it is young people feeling isolated, or adults wondering about their place in the LGBTQ community.

With “Hola Papi,” Brammer illuminates his own ups and downs as well, like the time he took a job in a tortilla factory out of a misplaced desire to prove his Mexican-ness, or when his former childhood bully contacted him on a gay hookup app. He describes everything from how he came out in college (“in a fit of gay mania,” he writes), to a dysfunctional relationship with a Christian youth group member, to his own sexual assault.

“Hola Papi” has received mostly positive reviews. Kirkus Reviews called it a “sassy, entertaining debut collection,” praising it as “charming, instructional, and frequently relatable.” Brammer has also written for NBC News, The Washington Post and The Guardian.

In his book, Brammer, a self-described “ambiguously Latino potato” from “Satan’s Armpit, Oklahoma,” opens up about his own struggles with depression, anxiety and more. One time, a random negative tweet directed at him from a total stranger led him to attempt suicide. “The internet is an unnatural arrangement of community, and we are not wired to accept blatant hostility from strangers at a fast clip,” he reflected. “Usually when I receive negativity on social media, it doesn’t affect me — I don’t see those people as my peers. But it is harder on the gay or Latino internet, when the criticism is coming from there and it is personal, it hurts. If your perceived community turns on you, it is not a good experience.”

Building on a tradition — the advice column

Brammer noted that although he never set out to be an advice columnist, that genre of media is a place where female writers, along with other traditionally marginalized voices, have been able to gain a toehold in newspapers and publishing.

Brammer’s publisher calls him the “Chicano Carrie Bradshaw” of his generation, referring to Sarah Jessica Parker’s sex columnist character in “Sex and the City.” On a broader level, his writing is continuing a tradition that is familiar to Latino and non-Latino readers alike.

Beginning in 1998, the late Dolores Prida wrote the “Dolores Dice” (Dolores Says) column in Latina Magazine for over a dozen years. “We used to do surveys, and her column was more popular than our cover girls,” said writer and documentary filmmaker Sandra Guzmán. The former editor-in-chief of Latina, Guzmán considers hiring Prida for the column her greatest legacy at the magazine.

“Dear Abby wasn’t thinking about us. She wasn’t getting letters about experiencing racism in college or wrestling with assimilation,” Guzmán said. “Dolores Prida created a safe space where readers could share their problems.”

Many Latinos are not acculturated to going to therapy, Guzmán pointed out, and the “Dolores Dice” column was a way for readers to get advice from someone who could seem like a savvy cousin or a wise aunt. “It takes a special skill to answer questions and be funny and be light — and also profound and truthful.”

“Taking problems outside of your family is often not something that our communities approve of,” Guzmán added, “So Dolores’ column was a place where readers could seek counsel on relationships, career advice, and cultural identity.”

In a similar vein, from 2004 to 2017, writer Gustavo Arellano took questions from readers in his “Ask a Mexican” column. Like Brammer, Arellano’s original column began as a satire, then morphed into a syndicated column and then a book. “I started the column on the advice of my editor at the time, at the OC Weekly (in Orange County, California). We did it to fill up space, to make fun of the dumb questions people asked about Mexicans.”

“Never in a million years did I expect the column to take off,” said Arellano, now a columnist with The Los Angeles Times. At its peak, “Ask a Mexican” was reaching over 2 million people in 38 markets.

“People used to write and ask why Mexicans did certain things, like going to the beach with clothes on, or readers would make ignorant comments, but I saw it as a way to educate people,” Arellano said, noting that he got questions from all kinds of people, including both whites and Mexicans. He still writes “Ask a Mexican” in his weekly newsletter.

Brammer has received emails from around the world, including Morocco, India, Brazil and Japan. His column, he said, has helped him come to terms with events in his own life. “I’ve learned that there is no singular Mexican experience, no singular Latino or gay experience. I don’t consider myself an expert on things; but hearing other people’s struggles has helped me reckon with my own.”

In Brammer’s view, everyone is an author of sorts, as people sift through their experiences and craft narratives to make sense of their lives.

“Over the years, I have finally learned to stop looking for approval in places where I am not going to get it,” he said. “I can only do my best to make sure my head and heart are in the right place. And I hope my readers see that there is a lot of room for happiness, exploration and wisdom in all the things that make us our unique selves.”

Follow NBC Latino on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.