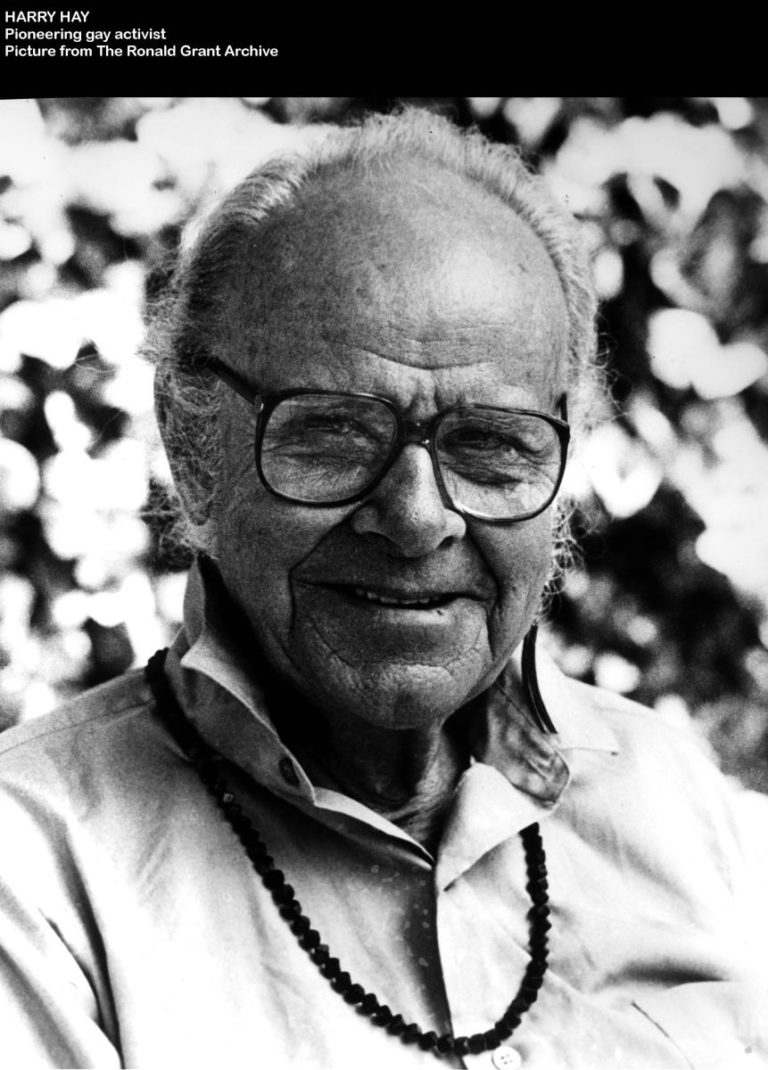

A homosexual, Socialist, writer, spiritualist and activist, Harry Hay would cofound a secret organization in 1950 that would become the origin of the American gay rights movement, and help shape and expound the notion that gay people were an oppressed, cultural minority whose unification would only create greater awareness and understanding.

Hay gravitated towards radical politics as a young adult

Born Henry Hay Jr. on April 7, 1912, in Worthing, England, Hay’s father was a mining engineer who moved the family to Los Angeles in 1919 where Hay would attend high school. Entering Stanford University in 1930, he soon abandoned lectures to return to Los Angeles and pursue a career in acting. It was during this period he met and formed a relationship with the actor Will Greer, who would go on to national fame in the role of Grandpa in the 1970s television series The Waltons.

Greer helped to introduce Hay to the concept of radical politics and Communist organizing. He encouraged him in his interest in Marxist theory, which led to Hay’s adoption of Socialism, and in which he hoped to find support for homosexuality. While attending a docker’s strike in San Francisco in 1934, Hay and Greer reportedly witnessed the shooting of strikers by U.S. national guardsmen. Both men joined the Communist Party USA soon after, with Hay now fully committing himself to left-wing labor and anti-racist campaigns.

He married a woman to not get kicked out of the Communist party

From early childhood, Hay said he recognized he was attracted to boys, not girls, and had his first sexual encounter at age 14. But the Communist party did not tolerate homosexuals and members urged Hay to settle down and get married. Hay married fellow party member Anita Platky in 1938 in a public attempt to quell his homosexuality and avoid suspicion. The couple adopted two daughters, Hannah Margaret and Kate Neall, during the mid-forties. Though the couple shared political beliefs and pursuits, Hay realized his sexual inclinations had not diminished and began seeking out same-sex encounters. He would later describe his marriage as “living in an exile world,” according to The Trouble With Harry Hay: Founder of the Modern Gay Movement by Stuart Timmons. The couple divorced in 1951.

Hay wrote his manifesto ‘The Call’ arguing that the homosexual community deserve equality

It was during his marriage to Platky that Hay began pursuing what he described as a call “deeper than the most innermost reaches of spirit, a vision quest more important than life.” The 1948 release of Sexual Behavior in the Human Male by Alfred Kinsey — which concluded as many as 10 percent of American men were exclusively homosexual — inspired Hay to believe it would be possible to form an organization of homosexuals by homosexuals, a movement which would help in the fight against discrimination. Emboldened, Hay wrote a prospectus devoted to the wellbeing of gay people, calling it “Bachelors Anonymous.” The manifesto, which would later become known as “The Call,” was the first to view homosexuals as a culturally “oppressed minority.”

Hay believed that all lesbians and gay men deserved equality, writing in 1950 that “in order to earn ourselves any place in the sun, we must with perseverance and self-discipline work collectively … for the first-class citizenship of minorities everywhere, including ourselves.” The same year he met Rudi Gernreich who would later gain fame as a designer of unisex clothing and in particular, the topless bathing suit. Hay and Gernreich soon became lovers, encouraging the other in their shared quest to establish a gay political movement in California.

In 1950, he helped form the Mattachine Society to unify homosexuals

Along with Dale Jennings, Chuck Rowland and Bob Hull, Gernreich and Hay held the first meeting of what would become the Mattachine Society on November 11, 1950, in Los Angeles. The name was based on masked, medieval French performers who satirized social conventions. Over the next three years, the secret organization quickly grew in membership through sponsored discussion groups for homosexuals, helping to raise awareness and encourage a minority group identity. Ratified in 1951, the Mattachine mission and purposes stated the group’s threefold aims “to unify” homosexuals “isolated from their own kind and unable to adjust to the dominant culture,” “to educate” and improve information about homosexuality and “to lead” homosexuals towards unification and education.

But Hay struggled within the group. His relationship with Gernreich had ended and his leftist politics and belief that gay people should not simply assimilate into a heterosexual-dominated society were often at odds with other members. In 1953, amidst growing media scrutiny of the organization, Hay was ousted from the group. Mattachine continued, but with less confrontational policies than Hay originally envisaged.

Hay immersed himself in West Coast progressive politics

In 1955 Hay was called to testify before a subcommittee of the House Un-American Activities Committee investigating Communist Party activity in Southern California. By then a publicly revealed Marxist, the allegations against Hay were dismissed and he spent the next decade and a half enmeshed in West Coast progressive politics including the anti-draft and anti-war campaigns. Fascinated by the growing counter-culture, Hay eschewed jackets and ties in favor of jeans, earrings, long hair and necklaces. In 1962, Hay met and fell in love with the inventor John Burnside, who would become his life partner. The couple participated in homophile demonstrations throughout the sixties during which Hay became chairman of the Los Angeles Committee to Fight Exclusion of Homosexuals from the Armed Forces, among other positions.

He remained highly critical of the mainstream gay rights movement until his death in 2002

Though the June 1969 Stonewall riots in New York garnered the gay rights movement a higher public profile, Hay stated that he “wasn’t impressed by Stonewall, because of all the open gay projects we had done throughout the sixties in Los Angeles. As far as we were concerned, Stonewall meant that the East Coast was catching up.” Later he would tell the Associated Press that “the importance of Stonewall is that it changed the pronoun from ‘I’ to ‘We,’ … By the time of Stonewall [homosexuals] thought we had always been a cultural minority.”

In 1978 Hay formed the Radical Faeries, a gay brotherhood community in which the rights of homosexuals were extolled alongside spiritualist teachings and New Age practices, and “hetero-imitation” was discouraged. Diversity was key to Hay, who came to be viewed as an elder statesmen within the gay community in the 1980s and 1990s, albeit a controversial one. He remained highly critical of the mainstream gay rights movement and would often take divisive stances, such as advocating for the inclusion of the North American Man/Boy Love Association (NAMBLA) in Pride parades. “The assimilationist movement is running us into the ground,” Hay said in 2000.

Still a largely unknown figure to many unfamiliar with the fight for LGBTQ+ rights in America, Hay died on October 24, 2002, at age 90. In the weeks before his death, Hay and Burnside registered as domestic partners in California.