(This article originally appeared on Next Avenue.)

As the modern LGBTQ rights movement gained momentum in the late 1950s, activists realized they faced a major roadblock.

Being gay wasn’t just considered a bad “choice” or something immoral, it was an actual medical condition listed in the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

If you were mentally ill, the reasoning went, how could you successfully lobby for equal rights or any rights at all?

The new documentary “CURED” details how pioneering LGBTQ-rights activists decided to take a stand against the medical establishment and eventually won. The APA finally removed homosexuality from the DSM in December, 1973.

“This is a little known story about a group of tenacious activists who refused to accept this oppressive label,” says Bennett Singer, who co-directed, produced and wrote “CURED” with Patrick Sammon. “They not only challenged it but won their battle and transformed the social fabric of American society.”

The film, which has been screened at festivals and other events, is slated to debut this October on PBS’ “Independent Lens.” “CURED” has won audience awards at both the New York and San Francisco LGBTQ+ film festivals, has several virtual screenings available and has been optioned by 20 Century Television for a scripted series from the co-creator of “Pose.”

Without this “instant cure,” as one newspaper put it, LGBTQ-rights milestones like marriage equality, the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell and the inclusion of transgender people in the military might not have been possible or might have taken even longer to accomplish.

“The ripple consequences and legacy of the change to the DSM can’t be underestimated,” Singer says. “It was illuminating and inspiring to see how consequential this fight became and how far the ripples extended.”

‘Instant cure’ took years

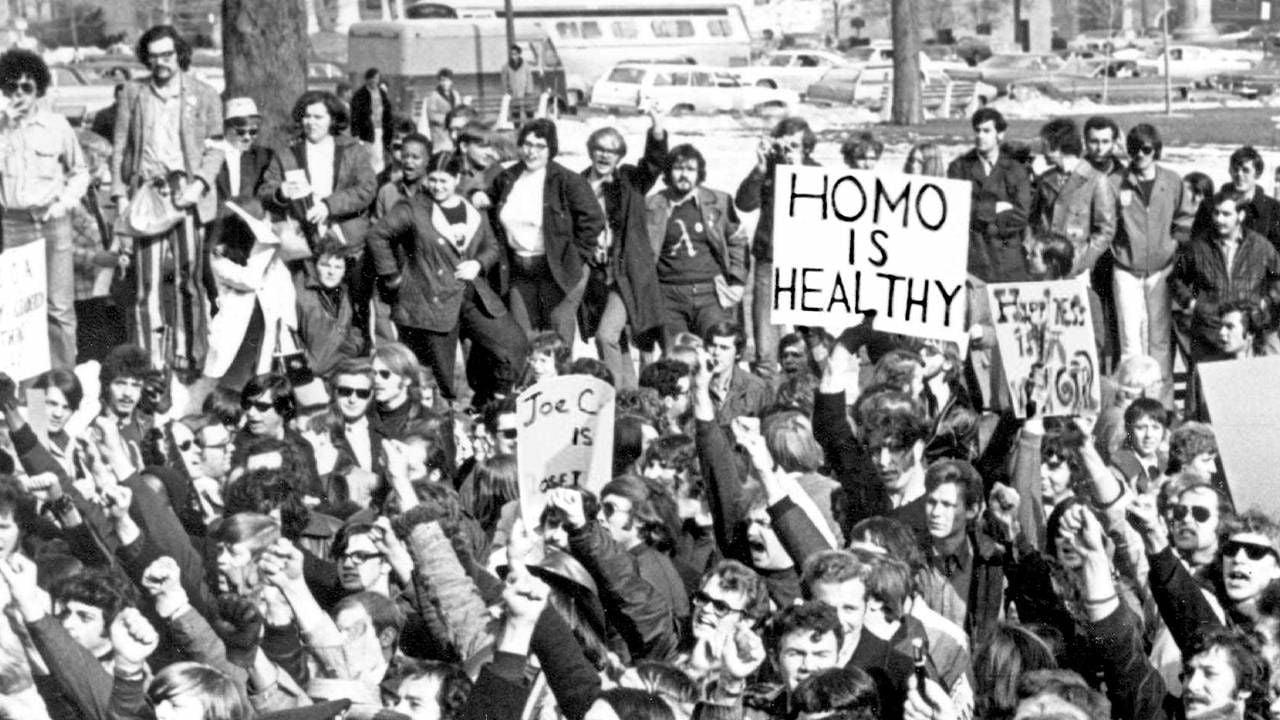

Combining archival footage and materials with on-camera interviews with key figures, the film vividly captures a battle fought over 81 words and waged at professional meetings, on TV and via live protests.

“We tried to create a sense of suspense and tried to underscore that victory was by no means inevitable,” Singer says.

Led by the late Frank Kameny, Barbara Gittings and other pioneering activists, this effort straddled different eras — and approaches — of the LGBTQ-rights movement, incorporating in-your-face tactics with working for change from within.

Starting in 1970, activists began to disrupt APA meetings, culminating in a dramatic moment at the 1972 meeting in Dallas. There, a man wearing a Nixon mask and known at the time only as Dr. H. Anonymous stood up and declared: “I am homosexual. I am a psychiatrist.”

To have a member of their own profession declare he was gay, even while in disguise, represented a completely new experience for many and helped foster more constructive dialogue between activists and APA members.

“One fascinating piece of the evolution is to think about the shift from confrontation and invasion of APA meetings and gatherings of mental health professionals to dialogue,” Singer says. “For many of these mental health professionals, it seemed like the first time they had sat down with healthy gay people who didn’t want to be viewed as sick.”

“It was the beginning of a transformation of how gay people presented themselves and how psychiatrists and psychologists perceived these people,” Singer added.

Given the advanced ages of the surviving participants, the filmmakers felt an “urgency” to capture their remembrances on film.

Leaders like Kameny and Gittings had already died. But they were able to speak with people like Kay Tobin Lahusen, who photographed the LGBTQ rights movement extensively and was Gittings’ life partner; Harry Adamson, a friend of Dr. H. Anonymous, aka Dr. John Fryer, who helped preserve his papers; and Ronald Gold, a former journalist who gave a key speech to the APA called “Stop it, you’re making me sick!”

Lahusen died on May 26, 2021 at 91; Adamson passed away in April 2021 and Gold in 2017, shortly after sharing his story for “CURED”.

“His [Gold’s] death was a really poignant reminder that the main storytellers in this film are in their 80’s and 90’s, and our goal was to have their first-person testimony driving the narrative,” Singer says.

Using science to debunk myths

Key to the strategy to win over skeptical clinicians was to include gay psychiatrists like Fryer, who practiced in Philadelphia, as well as straight allies from within the profession.

There’s no film footage of Fryer’s landmark speech, but the “CURED” team unearthed the audio tape from among the 217 boxes of his materials at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

“I spent some time dutifully listening to those tapes because it wasn’t clear from the inventory what was there,” Singer recalls. “It was miraculous to find that one tape of his historic 1972 speech from the APA meeting in Dallas.”

Although both sides of this issue claimed that facts supported them, LGBTQ activists and their allies successfully debunked the junk science behind conversion therapy, electroshock therapy and other failed treatments of the time.

“It was an astounding twist of fate that Frank Kameny had gotten his Ph.D. in astronomy from Harvard and was a scientist at the core,” Singer says. “He was the absolutely perfect person to pick at the rigor and arguments being made by the proponents of the mental illness label. The debate over science and what constitutes good science — where is the data? — all of the questions that Kameny raised so cogently are at the heart of the story.”

The battle still isn’t over

Despite the steady progress of the LGBTQ-rights movement in recent decades, this battle to be seen as whole people entitled to the same civil rights as everyone else isn’t over. Witness the drive in many states to block transgender rights or deny access to medical treatments for transgender youth.

“There are very clear and chilling parallels between the way gay men and lesbians were treated and perceived in the ’60s and ’70s and the way trans people are being attacked now and being considered ‘disordered,'” Singer says.

The film also shows the benefits of lifting the stigma of being misdiagnosed as sick.

“It speaks to the importance of having dignity and self-worth and the value of being treated as healthy individuals by an institution like the APA,” Singer says. “Barbara Gittings put it brilliantly when she said that an albatross has been lifted from our neck.”