Over the past decade, significant pillars of the evangelical community have wavered in their convictions about marriage and human sexuality. In 2014, World Vision announced it would hire Christians in same-sex relationships—only to reverse course after a backlash threatened donations.

Things have gone differently for Bethany Christian Services, one of the country’s leading adoption providers, which recently disclosed its plan to place children with same-sex couples. While the organization stressed that “discussions about doctrine are important,” the decision effectively severs a Christian doctrine of marriage from the practice of adoption.

Conservative evangelicals have reacted by trying to purify the ranks of the faithful. In 2017, the Nashville Statement, put out by the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, responded to weakening evangelical adherence to Christian teachings on sexuality. The ill-fated effort did little to build evangelicals’ confidence that their witness on sexual ethics would be simultaneously orthodox and also welcoming toward LGBT individuals.

Nonetheless, there is reason to be seriously concerned about the future of evangelical communities in an increasingly post-Christian America. The Supreme Court’s decisions in Obergefell v. Hodges, which legalized and legitimized same-sex marriage, and Bostock v. Clayton County, which extended nondiscrimination protections to LGBT individuals, have ratified the long reshaping of America’s norms on marriage and sexuality.

They have also raised serious questions about the rights of faith communities. Despite enjoying unprecedented access to the White House during the Trump administration, evangelicals secured few religious liberty wins. For example, the First Amendment Defense Act, championed by conservatives as a robust form of protection, never made it out of committee, despite a united Republican Congress. President Trump himself said it was a “great honor” to be called the most pro-gay president ever, and the First Lady publicly endorsed gay and lesbian equality.

Earlier this year, the Equality Act introduced yet another hurdle for orthodox Christians. The bill—which in February passed the first stage of becoming law—would have wide-ranging implications for Christians. Most notably, it would throttle religious liberty protections for Christians who dissent from the emerging regime of LGBT rights.

The Equality Act is unlikely to pass the Senate. (Its outcome is yet unknown at the time of publication.) But even if it doesn’t, the bill carries symbolic and cultural significance. As an inflection point in the life of our nation, we should be unnerved and also chastened by it. The headwinds against socially conservative positions on marriage and religious liberty are stronger than ever.

Evangelicals should unequivocally oppose bills of this nature (and there will be more). But we should accompany those noes with a good-faith effort to live together as fellow democratic citizens with LGBT individuals. One way to do that is by helping to secure nondiscrimination protections for them that simultaneously offer substantive religious liberty protections.

The headwinds against socially conservative positions on marriage and religious liberty are now stronger than ever.

Congressman Chris Stewart recently re-introduced one such bill: Fairness for All, which attempts to expand LGBT rights while preserving religious exemptions. The legislation is imperfect, but it offers Americans a potential way out of the zero-sum game that conservatives and LGBT activists have been locked in for the past 40 years.

Talk of compromise is perilous, of course. Progressives often express open hostility toward conservative Christians. Evangelical activists have also seen those on the Left engage in a disingenuous “dialogue” that effectively aims at changing the church’s teaching on human sexuality.

Given progressives’ disinterest in accommodating religious believers, we have reason to dismiss efforts like Fairness for All. But we might want to reconsider some of the underlying reasons for our aversion to efforts like it. Though conservatives often decry the “victimhood” logic of identity politics, we have at times practiced our own form of it: While denouncing our progressive oppressors, we maintain a powerful narrative about our own moral purity in the sex and marriage culture wars.

Yet the story is more complicated, especially as we look back to the height of the sexual revolution. By adopting a perfectionist, populist politics that often demeaned and disrespected our LGBT neighbors, we evangelicals helped create the conditions for our social marginalization.

Getting behind this history in order to understand the origins of our particular social moment does not mean compromising fidelity to Scripture on sex and marriage. If anything, this diagnostic work is necessary to understand how Scripture might inform our responsibilities to our LGBT neighbors here and now.

As an evangelical theologian, I affirm without hesitation that marriage is between a man and a woman, that biological sex should inform a person’s “gender identity,” and that surgical or chemical efforts to alter a person’s sex are an illegitimate and unmedical means of responding to social or psychological challenges.

Yet as citizens living in a pluralist society, we cannot draw a straight line from these convictions to political judgments. For evangelicals, that means we should undertake the task of understanding where LGBT hostility comes from and what legitimacy it may or may not have.

Only by coming to terms with our own history of engagement on these issues will we be able to speak confidently again about the politics of sex, instead of allowing fear to inflect our speech. An evangelical witness on these issues must still sound like good news. In that sense, it must be marked by mercy. It is bitterly ironic that, having failed for so many years to practice the preeminent virtue of a democratic society, conservative evangelicals now stand in need of it.

The way toward retrieving it, both for ourselves and for the society in which we live, lies through the tangled path of history that brought us to this juncture.

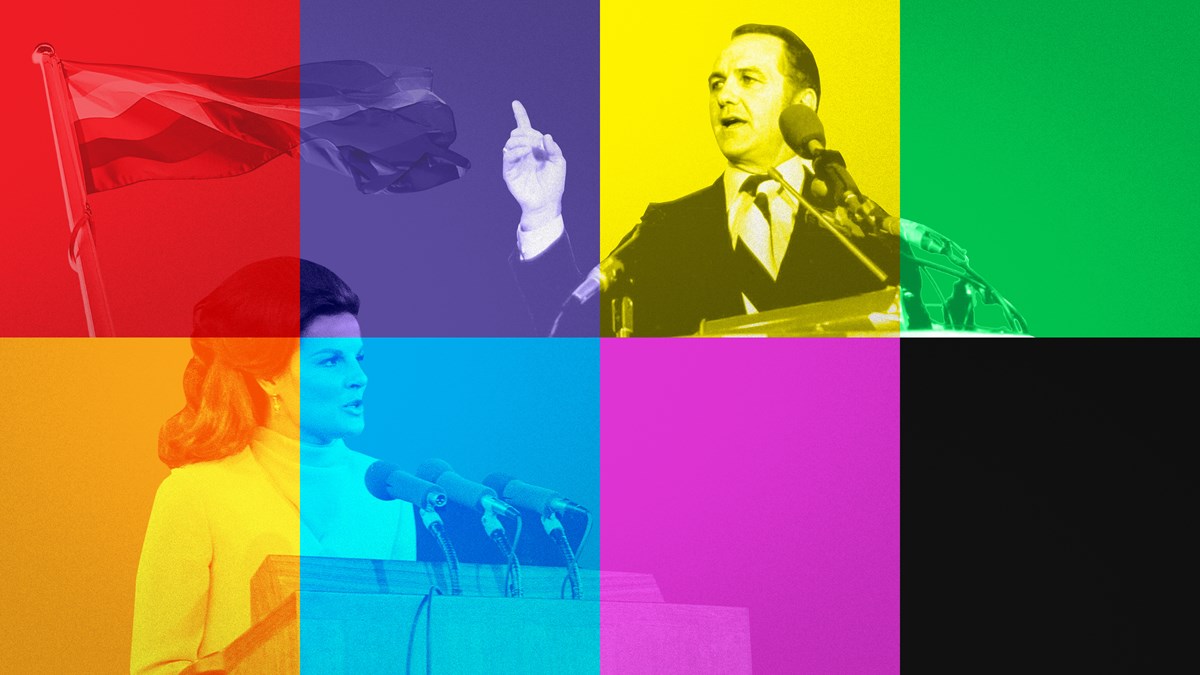

America’s culture war over sexuality exploded in Miami. In 1977, Anita Bryant campaigned against the city’s recently passed nondiscrimination ordinance. Bryant, a beauty contest winner and a Top-40 singer, was the face of the Florida Citrus Commission.

In the years prior, an increasingly confident gay liberation movement had successfully passed nondiscrimination ordinances across the country. But Bryant’s opposition campaign was successful. While concerns about the ordinance’s lack of religious liberty protections buoyed her effort, Bryant’s rhetoric about the threat gay people ostensibly posed to children was the campaign’s lasting legacy. Her victory quickly became a crusade. She established Save Our Children, an organization aimed at restricting LGBT rights, and promised to do for the country what she had done in Miami.

Bryant’s nationalization of her campaign, though, came with collateral damage. Only months after Bryant’s victory, Christianity Today asked Billy Graham about her. His answer was circumspect. While praising her courage and lauding her for “emphasizing that God loves the homosexual,” Graham also suggested that he would not have said “some things she and her associates said … in the same way.”

Graham added that, while he saw his vocation as focused on preaching the gospel, he “was also fearful that her campaign might galvanize and bring out into the open homosexuality throughout the country, so that homosexuals would end up in a stronger position.”

Graham was proved right. Emboldened by successes in overturning nondiscrimination ordinances across the country, conservatives soon overreached. Those actions further intensified the LGBT movement and motivated its fundraising and organizing.

In 1978, for example, California legislator John Briggs proposed a ballot initiative in that state that would have required schools to fire LGBT teachers. Despite favorable polling at the start of the campaign, the initiative failed by over a million votes, as California residents came to realize how punitive it was.

The measure also galvanized the LGBT community. As Tina Fetner argues in How the Religious Right Shaped Lesbian and Gay Activism, Bryant and Briggs inadvertently reinvigorated what had been an increasingly dormant movement, giving it a more militant and oppositional edge than it had previously. Activists personalized the issue for the first time: Openly gay politician Harvey Milk encouraged people to come out of the closet to their friends and neighbors, reshaping public opinion about the challenges they faced.

The template for the culture wars had been more or less set. Conservatives would make inflammatory appeals to populist, anti-LGBT sentiments, in turn fueling opposition.

These dynamics were solidified when the conflict came to Colorado in 1992. Evangelicals concerned about nondiscrimination ordinances in Denver and Boulder followed the same playbook by pursuing Amendment 2, which was supposed to prevent Colorado cities from enacting nondiscrimination ordinances.

While fighting for the amendment, social conservatives distributed 100,000 pamphlets across the state. Written by psychologist Paul Cameron, they emphasized, among other things, that gay men ingest fecal matter in their sexual practices. The television campaign intentionally presented the most flamboyant, non-bourgeois depictions of gay pride parades—ostensibly to show the “reality” of the LGBT movement, but in effect to generate fear.

When Denver television stations declined to play the ads, organizers denounced media bias. The tactic worked. On the night Bill Clinton was elected, Amendment 2 shocked Colorado residents by passing 53 percent to 47 percent. Some 16 years later, California voters reenacted a nearly identical pattern when—after a tumultuous fight—they simultaneously prohibited gay marriage with Proposition 8 and made Barack Obama president.

However, no moment was so discrediting for evangelicals as Colorado’s Amendment 2—in part because the legacy of its rhetoric swallowed up conservatives’ reasonable arguments. Evangelical populism has long faced this dilemma: Careful arguments don’t move votes, but the extremist rhetoric necessary to win tends toward disrespect and also generates a backlash.

Amendment 2’s success in Colorado typified this problem. For one, the animus that conservatives showed toward LGBT people shaped tech entrepreneur Tim Gill, who in response began to devote his vast fortune to the expansion of LGBT rights. In the years to come, his strategic contributions would make him one of the country’s most influential figures in sexual politics.

Moreover, prominent academics became embroiled in Amendment 2’s subsequent legal dispute, which undermined trust and effectively ended any chances of an elite-level consensus on these questions.

Amendment 2’s drafters insisted that its text required no moral judgment about homosexuality. Yet the case hinged upon the question of whether same-sex sexual activity is reasonable. Legal philosophers Robert George and John Finnis gave one reading of the Western philosophical tradition, while philosopher Martha Nussbaum gave another. The debate ended in acrimony and even included accusations of perjury.

George and Nussbaum would go on to effectively set the terms of the debate. While George continued to make the case for traditional sexual ethics, Nussbaum argued that positions like his were probably rationalizations for animus. Nussbaum would eventually win, both in the courts and the culture. The case went to the Supreme Court as Romer v. Evans, giving gay rights supporters their first victory at the Supreme Court and setting the trajectory for all that would follow.

While most evangelicals sought to treat their neighbors with respect, some of their institutions and leaders failed to expunge the dehumanizing rhetoric as they ought to have done. In 2012, for instance, the Family Research Council (FRC) gave an award to pastor Ron Baity for his efforts on Amendment 1 in North Carolina, which prohibited the state from recognizing gay marriages.

When video was discovered showing Baity had compared gay people to maggots, the FRC argued that he was given the award not for his “misstatements” but for “his example of standing for the truth and for his 42 years of ministry.”

From the outside, it was easy to believe that social conservatives tolerated degrading sentiments toward the LGBT community up until those calloused words became a political liability. But even then, the people responsible—like Cameron or Baity—were often quietly sidelined rather than actively repudiated.

The story that evangelicals are (merely) victims of progressive aggressors not only fails to account for the ways in which the LGBT movement was shaped by populist evangelical rhetoric and tactics. It also forgets that the gay liberation movement was a direct response to the systemic and pervasive exclusion of lesbian and gay individuals from the structures of our public life—including from America itself. Perfectionism in politics breeds radicalism in response.

Again, the current shape of the progressive LGBT community cannot be understood without acknowledging the background against which it was formed. While this context has been almost totally forgotten by both evangelical and progressive activists, it was recounted most recently by none other than conservative Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito.

In his dissent to the expansion of LGBT protections in Bostock, Alito cited a striking litany of past exclusions. In the 1940s and ’50s, gays and lesbians who worked in government were not given security clearances. They were barred from being teachers in some states and also faced the risk of losing their licenses to be doctors, lawyers, or even beauticians for engaging in same-sex sex acts.

They were even denied entry to the country by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 because they were alleged to have been “afflicted with psychopathic personality.” “To its credit,” Alito concluded, “our society has now come to recognize the injustice of past practices.”

Ironically, though, the pathologization of homosexuality used to justify these mid-century restrictions cleared the ground for both the assertion of “gay pride” on the one side and the failings of the “ex-gay spokesmen” on the other. As historian Heather White has argued, pathologizing homosexuality made it central to a person’s character and identity. That move eclipsed any distinction between the act and the person, or the sin and the sinner, which many evangelicals would later try to retrieve. But it also meant that gay people were forced to choose between the shame of being irremediably disordered and the pride of embracing their identity.

Not surprisingly, many chose the latter. The now-outdated slogan “born this way” inverts the therapeutic pathologization of homosexuality, even while sanctioning it with the authority of nature. Rather than disentangling their opposition to same-sex unions from this therapeutic framework, conservative evangelicals openly embraced it. Focus on the Family and other organizations employed “ex-gay” spokespeople to counteract the emerging narrative that homosexuality was both innate and fixed.

But they failed to recognize that ex-gay individuals who made “liberation from homosexuality” their vocation continued to be defined by it. A series of spectacular hypocrisies followed, undermining the movement’s credibility and further eroding the Religious Right’s political power.

Where should today’s evangelicals go from here? One possibility would be the path we did not take, which was originally hinted at by the first editor of this magazine, Carl F. H. Henry, in October of 1980. In an essay reflecting on the emerging Religious Right, Henry welcomes the “resurgent evangelical interest in politics” but worries that this involvement “may eventually become as politically misguided as was the activism of liberal Christianity earlier in this century.” In Henry’s view, the Religious Right’s “social vision is fragmentary, often lacks substance and strategy, and focuses mainly on a one-issue or single-candidate approach.”

A broader social vision, Henry thought, would help evangelicals avoid being reduced to a special-interest group and ensure they focus on those “concerns that transcend self-interest and coincide with universal human rights and duties.”

Henry suggests that the “primacy of the family as a lifelong monogamous union” is one point of evangelical emphasis. Henry infers from this that “legislation should benefit family structures, not penalize them” and that legislation should “preserve the civil rights of all, including homosexuals, but not approve and advance immoral lifestyles” (emphasis added).

Evangelicals once argued that nondiscrimination protections for LGBT people constitute “special rights.” So we should not overread Henry’s caveat. Yet while he often issued jeremiads about the decadence of secular culture, he was just as likely to argue that evangelicals were complicit in American cultural decay. And his denunciations of sexual degradation rarely—if ever—singled out LGBT people for special attention.

While Henry was emphatic about evangelicals’ need for a “social ethic” and for political action, he argued that “evangelical leadership in this reach for political influence and power” missed the “extent to which American evangelicalism was being swamped by the very culture that it sought to alter.” His relative lack of attention to the question of what we now call LGBT rights is indicative of the breadth of his concern: He saw that the fundamental challenges facing America could not be pinned on one group and that evangelicals themselves were hardly exempt from them.

Retrieving such a stance might help faithful LGBT Christians feel more at home in the church. As we evangelicals fought political battles over sexuality, we heightened the contrasts between the two worlds and in so doing ignored people in our own congregations who wrestle with their sexual desires and gender identity. This approach also intensified anxieties about faithful LGBT people in our midst and often alienated those whom we sought to help. As Tanya Erzen notes in Straight to Jesus, her careful depiction of an ex-gay ministry, participants often distanced themselves from the politics of the ex-gay movement.

While the ground has now shifted beneath evangelicals’ feet, we remain trapped in a heated conflict with a progressive LGBT community that has steadily gained the upper hand. An evangelical politics cannot ignore its own precarious position or be sanguine about the prospect of persuading those who strongly dislike our views. Nor are we permitted to be fatalists about finding common ground.

Evangelicals are people who stress the ongoing and never-ending opportunity for conversion, both for ourselves and for those who oppose us. When we come to Jesus, we confess our sins and live within God’s forgiveness—even if not our adversaries’. The gospel has the power to burst apart the ossified categories that limit our political imaginations. In announcing it, we invite the world to consider that, whatever has happened in the past, we can start anew.

A democratic order cannot survive unless its citizens are willing to accommodate each other. As the evangelical theologian Oliver O’Donovan has written, a “liberal society is marked by a mercy in judgment.” Mercy is the highest of all God’s qualities. It is, as Shakespeare understood, “mightiest in the mightiest,” such that earthly power comes nearest God’s when “mercy seasons justice.”

Mercy is an evangelical virtue. It is grounded ultimately within the free and lavish grace of God, who can forgive debts and sins while suffering no harm or loss. Yet evangelicals’ politics have rarely embodied it. We have often used the law to eradicate vices. We now find ourselves in a position where progressive LGBT activists must decide whether to treat us better than we once treated them by extending recognition through protections that they were once denied.

By adopting a perfectionist, populist politics that often demeaned and disrespected our LGBT neighbors, we evangelicals helped create the conditions for our own social marginalization.

For evangelicals to speak uncompromisingly about the goods of marriage and the integrity of the body, we must face up to our failures to do so in the past. The LGBT community has its own missteps and mistakes to account for. But as any good evangelical knows, denouncing the sins of others does not exonerate one’s own.

Mercy needs reasons, so if social conservatives want to live in a world that accommodates us, we must take responsibility for our own errors. Judgment “begin[s] with God’s household” (1 Pet. 4:17). By honestly recounting our missteps, evangelicals might give progressive LGBT activists a reason to look afresh at our convictions about marriage and the body. We exhibit confidence, not accommodation or weakness, when we forthrightly acknowledge our failures to embody the truths we affirm.

It is of course highly implausible that the progressive LGBT community will respond to such a posture. Trust is only gained over time, and it is special pleading for evangelicals to suddenly discover the goods of pluralism or tolerance. Yet there are still reasons to take that stand and to pursue consensus legislation.

For one, while evangelicals have sometimes over-emphasized the legal approach to transforming society, the law is still a tutor. It shapes a culture, even while representing its mores.

If a community is divided, the law might help foster social peace. The genius of the American constitutional system is that radical factions are moderated when they win representation (rather than being handed judgments by a court). Giving a legislative voice to a consensus effort might relieve the social pressure and hostility that have built up between the two communities.

The progressive LGBT community also has pragmatic reasons to extend mercy, though they may not realize it. For one, they stand on the cusp of repeating the Religious Right’s mistakes by embracing a political perfectionism that would stamp out their opponent. We have already seen glimmers of how a backlash against progressive ideologies might take shape. For instance, J. K. Rowling recently created an international storm by voicing her concerns about transgender ideologies. By contrast, it seems nearly unimaginable that a celebrity of her stature would denounce same-sex unions.

The arguments for gay marriage are easy and appeal to widespread intuitions: “Love is love” is insipid but also disarming. However, the arguments for trans rights run against the grain of widely held intuitions that sex and gender belong together. In that context, aggressive efforts to enshrine these ideologies in law and public policy are more vulnerable to populist revolts.

Additionally, the progressive narrative that history will inevitably culminate in the global triumph of LGBT rights is simply hubris. Pride still goes before a fall, and the international advancement of their movement is by no means inexorable.

Yet we should also pursue consensus legislation because the American experiment is worth preserving. The hostility between social conservatives and the progressive LGBT community for the past 40 years has not yet meaningfully imperiled the stability of our political order. But our society’s reserves of social trust are being depleted. When employment was relatively secure, government seemed to function, and we had meaningful, nonpartisan interactions with our neighbors, our fundamental differences on sexuality could be relatively quarantined. But now, as unrest increases, the stakes go up for reaching a settlement that represents all Americans.

We will face greater challenges in the days to come, and we need to face them together. In her poem “The Hill We Climb,” read at President Joe Biden’s inauguration, Amanda Gorman acknowledged the “force that would shatter our nation rather than share it.”

Yet her stirring call for unity held out hope that division would not be America’s final word.

“If we merge mercy with might,” she said, “and might with right, then love becomes our legacy and change our children’s birthright.” It was a bold endorsement of a virtue long neglected—one in desperate need of retrieval.

Regardless of what happens with the Equality Act and other bills like it, evangelicals still face the more fundamental task of forming communities that bear witness to the goods of marriage and the body in ways that are saturated by faith, hope, and love.

Such a task demands an uncompromising fidelity to Scripture and a deferential humility to the theological inheritance we have received. If, as Carl Henry once thought, we live in the “twilight of a great civilization,” we also live in the unending dawn of Christ’s reign—a dawn that must make our hearts glad, regardless of the threats to our liberties. Only when we embrace the joy of the living God, Jesus Christ, will our commitment to marriage between a man and a woman ring out to the world with a clarity and grace that inclines them to take heed and listen.

Matthew Lee Anderson is an assistant research professor of ethics and theology at Baylor University.

Have something to add about this? See something we missed? Share your feedback here.