Scotland was the first country in the UK and one of the first in the world to provide PrEP via sexual health clinics as a standard provision of its national health service. In January this year, it became only the second place in the world, after New South Wales in Australia, to be able to show that the introduction of PrEP had led to a significant fall in HIV infections, not only in gay and bisexual men taking PrEP, but also in men who did not, proving that PrEP could have real population-level effectiveness in preventing HIV.

This success was reviewed in a lunchtime workshop and a couple of other presentations at last week’s joint British HIV Association and British Association of Sexual Health and HIV virtual conference.

The Scottish PrEP programme: achievements so far

Professor Nicola Steedman, Scotland’s Deputy Chief Medical Officer, outlined the recent history of HIV diagnoses and PrEP use in Scotland since the PrEP programme began in July 2017.

There are currently 5600 people living with HIV in Scotland, and 167 were newly diagnosed in 2019, the last year with full data. In 2017 half of all new diagnoses were in gay and bisexual men but by the end of 2019 this had declined to 37% of the total. The proportion of infections in people who acquired HIV heterosexually did not decline, and in people who inject drugs it rose, from 12% to 16%.

As explained in our previous report, the proportion of newly diagnosed infections that were recently acquired declined by 35% over this time. This allowed annual incidence – the proportion of the tested clinic population who acquired HIV during the previous year – to be calculated. This fell by 75% in gay and bisexual men taking PrEP, but also by 32% in gay men not taking PrEP.

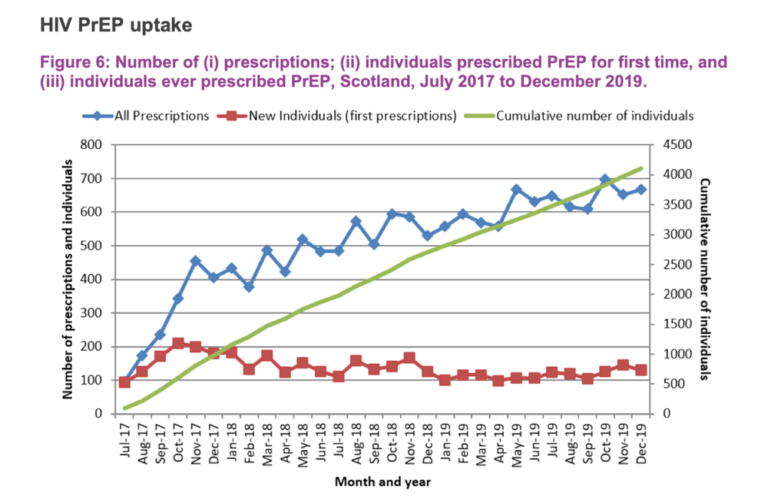

There are roughly 4500 people who have ever been prescribed PrEP at least once in Scotland (per head of the adult population, this would equate to about 50,000 people in England). Each month, about 125 people get their first prescription. Professor Steedman said it was estimated that there was a stable cohort of about 2000 people in Scotland taking PrEP regularly. The vast majority were gay and bisexual men, with only 45 people prescribed PrEP falling into other categories.

The most common reason for prescribing was that the person had had condomless sex with more than one partner in the last year and thought they were likely to do so in the future. Most of the others were people with partners diagnosed HIV positive.

Among the gay and bisexual men – the group for whom this is an option – only 26% initially wanted event-based dosing, but over the two years surveyed this rose to 44%.

Who didn’t get PrEP, and were opportunities missed to offer it?

The rest of the PrEP presentations looked at who was being left out of Scotland’s PrEP success story – namely, anyone other than gay and bisexual men.

Dr Ceilidh Grimshaw of NHS Glasgow had conducted an analysis of those diagnosed before 2017, compared with those diagnosed in 2019, to confirm the apparent decline in the proportion that were gay and bisexual men. She found that people diagnosed after the PrEP programme began were less likely to be men, less likely to report sex between men as their exposure category, were more likely to have acquired HIV outside Scotland, and were more likely to be Black African. There was no change in terms of age or deprivation.

One part of the explanation for this was only 1% of people were prescribed PrEP using the ‘catch-all’ criterion that, in the opinion of their physician, they had been ‘at equivalent risk’ of HIV to people in the other categories. In other words, the health system’s criteria for PrEP concentrates on exposures more likely to have happened to gay men.

Introducing broader criteria was only part of the answer, however. One really interesting finding was that there was only a small extra proportion of people diagnosed with HIV whose infections could have been ‘potentially prevented’ by existing PrEP services. These potentially preventable infections were defined as people who had attended a sexual health clinic and had had a (negative) HIV test in the last year.

To the surprise of the researchers, only 8.6% of infections diagnosed before the introduction of PrEP, and 6.6% of those diagnosed afterwards, fell into this category (though 29% of recently-acquired infections did, probably because these are more likely to be found in frequent testers – who are also more likely to be gay men).

This was primarily because, by and large, the people diagnosed were not regular users of sexual health clinics – only a third of people diagnosed with HIV had attended a Scottish sexual health clinic pre-diagnosis and only one-seventh of heterosexual men and women had done so.

In other words, people who could potentially benefit from PrEP are not being detected, evaluated and offered it partly because the way current criteria are used excludes them, and partly because they do not seek health care at the clinics where PrEP is currently offered.

Community voices

Professor Paul Flowers of Strathclyde University summarised the findings of three qualitative studies of people’s opinions about PrEP, covering Black women, people who inject drugs, and trans and non-binary people.

There were findings in common, particularly the fear of stigma, exposure and shame that might accompany seeking PrEP. The people of colour added that PrEP education was not conducted within their social networks – they had to venture into the world of health care to encounter it – and that PrEP criteria and the way PrEP was presented were not attuned to community norms and expectations of safer sex and behavioural norms, particularly for women.

The participants stressed that community norms should be seen as an asset, not as a barrier, to PrEP education: that publicity material should be designed to reinforce rather than challenge these in a way that laid emphasis on PrEP as a self-protective behaviour.

The people who used drugs were keen to engage with PrEP and saw it could have substantial benefits, but noted that the unpredictability of their lives as substance users would make accessing PrEP through a clinic difficult. They wanted to see PrEP offered in the places where other harm reduction resources were provided – within community pharmacies, via street outreach, and even via peers.

The trans people laid emphasis on PrEP being part of an integrated service that provided not only STI and HIV prevention but also gender-affirming therapy and mental health support resources, but it should be based clearly in resources run within their community, ideally with peer-delivered models of care.

Recommendations for improvement

Professor Claudia Estcourt of Glasgow Caledonian University presented the results of a qualitative study that asked people to focus specifically on the Scottish PrEP programme as it has been. They were asked to identify barriers to and facilitators of better awareness and access, uptake and initiation, and adherence and retention. The researchers interviewed 39 people who were using or had used PrEP, 54 healthcare professionals, nine largely female and Black African service users of HIV community-based organisations who did not use PrEP, and 15 staff of those organisations. The 39 PrEP users included five transgender people.

“People who could potentially benefit from PrEP are not being offered it because they do not seek healthcare at the clinics where PrEP is currently offered.”

Certain themes stood out. One was that PrEP’s introduction had been under-resourced and overly rapid, at least to reach communities not already aware of it. PrEP was deliberately introduced with little advance publicity for fear services would be overwhelmed, but this had perhaps missed out on raising awareness.

It was not just the community of potential PrEP users who were not well prepared enough. Healthcare workers felt in general under-skilled in talking about sexual health risk, and identified two specific knowledge gaps. One was how to use intermittent PrEP, a subject both they and their patients found confusing. The other was about when it was safe to stop and re-start PrEP, and how. This was an area where healthcare professionals found themselves lacking in ways to accurately estimate and explain the risks and benefits of PrEP, versus the risks and benefits of no PrEP.

Service users found the system inflexible, particularly as they could not have PrEP prescribed at any appointment but only at designated ones, and also that the sessions were too short to explore other sexual and general health concerns. They valued practical adherence tips such as pill boxes and diaries, but also wanted more advice on coping with stigma. They commented that this came from both directions: people had experienced being shamed both for using PrEP, and for not using it.

Professor Estcourt also presented a poster at the conference which included a more detailed set of 25 recommendations for how Scotland’s PrEP service could be improved. There are too many to report in detail, but there is a big emphasis on the education and skilling-up of healthcare workers to be equipped with the latest evidence-based research on PrEP and HIV risk, as well as accurate and reassuring messages for users (such as how to start and stop, and reassuring users about transient side effects).

The recommendations conclude that “PrEP should be provided within care models which users and potential users find acceptable and which health services can roll out efficiently…These evidence-based recommendations could help optimise PrEP uptake and initiation to enable PrEP to reach all who may benefit.”

Since Scotland’s PrEP programme was introduced, just four people prescribed PrEP – one in a thousand – have acquired HIV, and all during periods when they were not taking the medication or had poor adherence. The aim of the proposed improvements to Scotland’s PrEP service was, as Dr Rak Nandwani, Scotland’s clinical lead for sexual health, said, was “To bring those four infections – and infections in general – down to zero”.