One night, Don Jackson, 38, had a dream that changed everything.

In the dream, he was approached by a man he recognized, a doctor who had killed himself after losing his medical license for coming out as gay. The doctor held out his hand, and Jackson took it. “Come, I will show you a place,” the doctor said.

A place. So simple, but it sounded majestic and urgent.

Jackson had long been outraged by the discrimination he and others felt for being gay, which had pushed him into activism and journalism. His byline frequently showed up in the underground papers that were the beating heart of the movement, and he was a worthy recipient of the vision that now unfurled before him.

The dreamscape transformed, and now he and the deceased doctor were on a mountaintop together. “I looked down into a little valley,” Jackson would recall, “and saw the tightly clustered town on a little river, its pastel-colored buildings glowing in the brilliant sun.”

He woke. It was a light-bulb moment. A place could be real and life-changing. It was one of those moments you remember for the rest of your life, when your whole past, your pain and pleasures, all your experiences and hopes, snap into clarifying focus, and you know at once what to do next. It was one of those moments moving from sleep to wakefulness, where the first thing you do is grope for a pencil before a shimmering idea slips away.

“I conceived the idea of the gay colony,” Jackson said, a utopia and “a quicker way to freedom.” A place where gay men and women could live without fear of discrimination.

Jackson needed a setting to match his vision. He had his eye on Alpine County, chosen for the simple reason that it was the least-populous county in California, with a shade under 500 residents—and fewer than 400 registered voters. If enough homosexuals moved there, Jackson reasoned, they could install their own government and establish a “gay symbol of liberty, a world center for the gay counterculture, and a shining symbol of hope to all gay people in the world.”

A turning point for Jackson’s activism had come months earlier on October 31, 1969—Halloween—when he and about 40 other gay men were peacefully protesting at the San Francisco Examiner building against a recent article that described homosexuals as “semi-men with flexible wrists and hips.” As they marched, a plastic container filled with black ink was dropped on their heads from the top of the building. The protesters used the spilled ink to put their handprints on the building and were arrested for “malicious mischief.”

The seeds were planted that something better could be out there when Jackson read a manifesto called “Refugees from Amerika” by Carl Wittman, who argued that for homosexuals to be truly free, “we must govern ourselves, set up our own institutions, defend ourselves, and use our own energies to improve our lives.”

Now Jackson needed people who could help turn the idea into reality. Though an introvert by nature, Jackson was a good listener and a deep thinker, and that made him the flag-bearer for this promised land. Tall and fit and a little shy in a way that came across as distinguished rather than weak, Jackson unveiled his plan to gay activists at the West Coast Gay Liberation Conference in Berkeley, California, on December 28, 1969. Encouraged by a the positive response, he began working with gay rights groups in the Bay Area to recruit volunteers to become the first pilgrims into Alpine County.

At first, Jackson planned to keep word of the project inside the gay community. “If I’d had my druthers,” he later said, “we’d have moved in quietly, as artists and writers, establishing a colony, and then announced the gay takeover as a fait accompli on the day the election returns came in.”

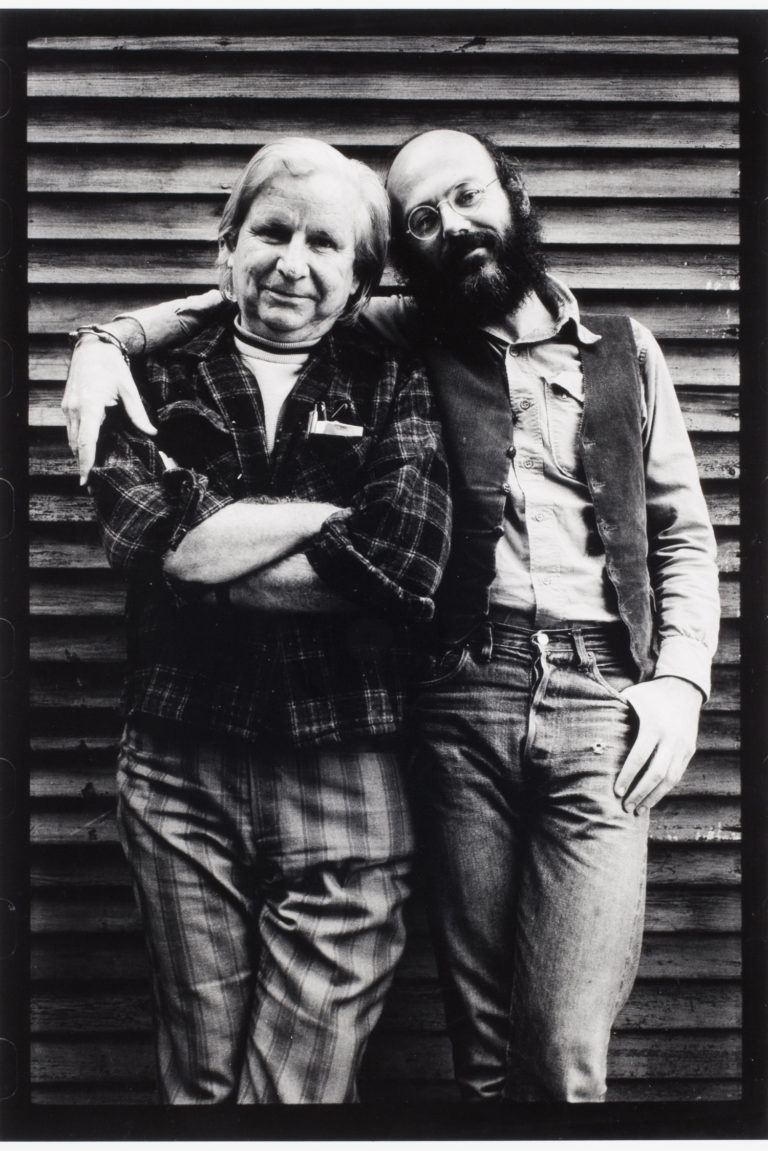

But then, in the summer of 1970, on one of his regular trips to Los Angeles, Jackson mentioned the project to Morris Kight.

Kight was a 50-year-old force of nature, a labor organizer and peace activist from Comanche County, Texas, who moved to Los Angeles in 1958 and immersed himself in what was then the rather staid “homophile” movement. Kight radicalized the movement by founding the Committee for Homosexual Freedom, which, in 1969, became the Los Angeles Gay Liberation Front, the third local chapter of GLF after New York City and Berkeley. Instantly recognizable by his thick, snow-white hair, Kight was a natural-born showman with sharp elbows.

But his devotion to the cause was absolute. Kight had been wanting to shine a light on gay rights issues like discrimination in jobs and housing. The gay takeover of a small, rural, and reactionary county in the California mountains could certainly do that.

“I thought, wait a minute,” Kight later recalled, “Don Jackson has a capital idea, and we must capitalize on it.”

Kight convinced Jackson to go public with his campaign. Respecting Kight as an elder statesman in the movement, Jackson agreed to publish an essay about his dream, which appeared in the Los Angeles Free Press, an underground paper.

On October 19, a phone call came into GLF’s office. The ringing was heard by Don Kilhefner, 32, who was usually at the office. In fact, he lived there. Raised in a Mennonite family in central Pennsylvania, he moved to California after college. In the summer of 1970, he became homeless when the car he had been living in got towed. He got permission to sleep on the couch in GLF’s office, becoming, by default, the group’s office manager.

On the other end of the line was Lee Dye, a reporter for the Los Angeles Times who covered health and science. His beat included gay issues, since, at the time, homosexuality was widely considered a mental illness.

“I hear there’s this thing called the Alpine County project. What’s that all about?’” Dye asked.

GLF had tried to get the Times to cover the story, but the paper was notoriously averse to reporting on gay issues. And Kilhefner was inspired by Jackson’s vision and approach. “I liked him because it was clear to me he was very intelligent, not a grandstander, diligent in his research, carried a certain humility that I speculate came from a sense of inner authority,” Kilhefner recalls. “Our conversations always had substance to them, no grandiosity, no bullshit, no pretending.”

With the reporter on the line, Kilhefner thought on his feet. “Oh my God, what a coincidence! We’re having a news conference tomorrow morning on just that subject!” He gave the office address at 577½ North Vermont Avenue.

In case Dye actually showed up, Kilhefner needed help to prepare. He hastily recruited two GLF organizers to stage an improvised presser at the office. Jackson couldn’t attend, but no matter. The move fit with GLF’s way of operating. “We were prepared to act at a moment’s notice,” Kilhefner says.

The office was in a second-floor apartment in a dilapidated two-story house in East Hollywood, “an old dowager of a building that had dignity,” as Kilhefner recalls. The aesthetic of the offices was very 1970s radical: photographs of Huey Newton, Frederick Douglass, and Che Guevara hung on the walls alongside a raised-fist poster. In a corner stood a small forest of picket signs, ready-made for any occasion: police brutality, anti-war demonstrations, gay rights marches. For the presser, they arranged chairs in front of a poster reading Gay People’s Victory! The following morning, Tuesday, October 20, Kilhefner and his two fellow speakers outlined the audacious plan to turn Alpine County into a “refuge where homosexuals can live without harassment.” Already, 479 homosexuals had volunteered to make the move. Once they met the 90-day residency requirement, the new gay majority would call a special election to replace the district attorney, county supervisors, and sheriff. The GLF, they explained, had by this point launched two “expeditions” to Alpine County and planned to begin the “migration” in less than three months, on January 1, 1971. The new arrivals would “live off the fat of the land”—as well as the $2 million in federal and state funding the county received annually. They predicted Alpine County would become a “mecca for homosexuals” as well as “straight curiosity seekers.”

“[It] will not be just a male society,” Kilhefner said. “Many of our sisters will join us.” Among those who’d already enlisted were doctors, lawyers, and teachers, he said. “We are still searching for two nurses, and we need one civil engineer to serve as director of roads.”

“It would mean gay territory,” Kilhefner continued, echoing Jackson’s original dream. “It would mean a gay government, a gay civil service, a county welfare department that made public assistance payments to refugees from persecution and prejudice. It would mean the establishment of the world’s first museum of gay arts, sciences, and history, paid for with public funds.”

“Just imagine what a great place that would be for summer rock concerts,” Kilhefner said, adding that eventually the group hoped to expand the concept across the country: “Almost any state in the union has an Alpine.”

Having explained all this, they looked out at the pool of reporters—one reporter, to be exact, Lee Dye. His story appeared in the Times the next day under the headline “Homosexuals Describe Plan to Take Over Alpine County.”

After that, Kilhefner remembers, “all hell broke loose.”

Alpine County erupted. It did not have a single traffic light but was suddenly the eye of a cultural storm. “Naturally, we’ll do everything we can to prevent anyone taking over our county,” Hubert Bruns, a rancher and chairman of the Alpine County Board of Supervisors, told the San Francisco Examiner when the news broke. “We have a real nice county here. We don’t know what we’re going to do if they succeed. We’ll try anything.”

The population of the county had settled to about 500 since the year 1900, when a boom in silver mining ended. The residents were proverbially hardy souls who reveled in the county’s spectacular scenery, rugged terrain, isolation, and harsh winters. Alpine County was also notable for its conservatism. In the 1964 presidential election, Barry Goldwater won the county with 57 percent of the vote. That was the highest percentage of votes Goldwater received among California’s 58 counties.

Now the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and wire services around the country picked up the story of the Alpine County project. “The residents of Alpine County are not amused,” Time noted in an article titled “Gay Mecca 1.” When the residents of the until-then obscure region tuned in their TVs to a special featuring Bob Hope, they found him talking about their county: “They had one demonstration up there, and the cops had to break it up, and instead of mace, they sprayed them with Chanel No. 5.” The residents of Alpine had suddenly been put on the national stage by a group trying to wipe them off the map.

On Wednesday, October 21, 1970—the day after the GLF press conference in Los Angeles—chairman Bruns, three additional supervisors, and District Attorney Hilary Cook made the four-hour drive from Markleeville to Sacramento, the state capital, to plead with Governor Ronald Reagan for help in repelling the gay invaders. The officials met with Reagan’s assistant legal affairs secretary, Richard Turner, who gave them bad news: if the homosexuals followed the letter of the law, Turner explained, there was no way to stop them.

“The people are very upset,” Bruns told a reporter after the meeting. “They”—the homosexuals—“will receive a hostile reception when they come.” Bruns added that “apples and peaches don’t grow well” in Alpine County’s cool mountain climate. “No fruit is very welcome up in our particular county.”

The reaction continued to darken and soon became threatening. A sign on the highway was defaced to read: watch for deer—hit a queer.

On the opposite side of the continent, extremist radio personality Carl McIntire was following the news about Alpine County with special interest. On his daily radio program, The 20th Century Reformation Hour (which was actually half an hour), McIntire announced he would be organizing a counterattack if GLF took over Alpine County.

McIntire, an ultraconservative fundamentalist preacher from Collingswood, New Jersey, was heard on hundreds of stations nationwide and raked in more than $3 million in small contributions from listeners every year. Broadcasting from the studios of WXUR, a radio station he owned in Media, Pennsylvania, McIntire railed against “communism, liberalism, racial integration, sex education, evolution and water fluoridation,” according to the Los Angeles Times. Critics complained that McIntire’s program was “highly racist,” “anti-Semitic,” “anti-Negro,” and “anti-Roman Catholic,” and in July 1970, the FCC revoked WXUR’s license for violating the agency’s fairness doctrine and failing to “keep . . . attuned to the community’s needs and interests.” But McIntire had appealed the ruling, and in October he was still on the air. “Homosexuality,” he would say, “must be met by the Gospel, and the attempt to dignify and legalize it will further corrupt society.”

“The day of silence has passed,” McIntire said of the Alpine County project, “and it is unthinkable that the Christians of the United States should sit by and permit a county to become a homosexual estate to embarrass this nation before the world . . . A new order, established after they have repudiated our system of morality, could very well become the first U.S. atheist and Communist county.”

McIntire promised to move enough of “our Christians” to Alpine County to keep the homosexuals from “obtaining majority control.” McIntire said his recruits would live in trailers and work as “missionaries.”

Don Jackson, dubbed the “Father of the Alpine Project” by the Los Angeles Free Press, was busy organizing an ad hoc coalition of activists that would come to be known as the Alpine Liberation Front (ALF), to pave the way for a smooth migration. According to scholar Jacob D. Carter, ALF formed committees to “organize farm communes, bee-keeping, a melodrama-theater beer-hall project, a crafts pleasure fair, ski resort, free clinic, free school, utilities, communications, housing, and consumers’ co-op.” ALF also published a pamphlet filled with information about Alpine County’s climate, economy, government and history.

While Jackson was busy in the Bay Area, on November 1, more than a hundred people crammed into the GLF’s Los Angeles office, separating into five committees. “Accumulation of money, material and personnel for the actual migration will be put into effect by these committees,” the group’s newsletter, Front Lines, reported, “with the enthusiastic support of much of the gay community around the country and the world.”

“The lid really blew off the establishment’s teapot when the GLF-LA told the world about the plans for taking over the tiny county of Alpine, California,” the newsletter boasted in an article titled “Alpine Co. Here We Come!” “Everyone in the State power structure from Ronnie Reagan to the Board of Supervisors of Alpine to ‘Dr.’ Carl McIntire . . . have been running around like lunatics trying to find some legal (or even not so legal) way to prevent the takeover of the otherwise insignificant area by gays.”

USC

Carolyn Weathers, a member of the group, remembers the excitement of a chance to “be like the pioneers in the covered wagons and take over Alpine County.” Weathers marveled at the energy of these packed Alpine County planning meetings. At one session, a burly man with a bushy beard sat in the corner, nimbly sewing a large blanket, the needle moving with remarkable speed. “Our brothers and sisters who go to Alpine are going to need our help in getting through the first winter,” he suddenly announced. “So come on, sisters, get busy helping me sew blankets!” And then he put his head back down and resumed sewing.

With group leaders such as Kight and mastermind of the impromptu press conference, Kilhefner, often busy on urgent business, the ranks had to rise up to prepare for the move. GLF volunteers fanned out across the city’s gay neighborhoods handing out flyers to recruit “Alpioneers.” They collected donations in a miniature covered wagon on Hollywood Boulevard, and collection jars were placed in gay bars all over the city.

GLF also received offers of support from outside the gay community. Economic Research Associates, the firm that had helped analyze the impact of Walt Disney World on the Orlando area, offered its services, and the California Libertarian Alliance endorsed the project.

“Your main resources are the freedom you offer plus the environment you are locating in,” Dana Rohrabacher, one of the libertarian group’s founders and later speechwriter to then-President Reagan, wrote in a letter to GLF. “The economic goods are perfect for some kind of a combination ski gambling resort.”

From the San Francisco hub of the project, Jackson wrote Kight frequently with updates and advice and included some flattery for the elder statesman of gay activism. “The people giving interviews should be rotated,” he wrote in one letter. “The younger longhairs are best for relating to the younger Gay Lib types, but you should do some of the interviews to give dignity to the project. Your name won’t have to appear in the press very many more times before you are listed in Who’s Who.”

As media attention increased, Jackson’s vision for the project expanded. “Events have changed my concept of what Alpine will be,” he wrote in another letter to Kight. “It has grown into a bigger issue than just Gay Lib or even just Gays. Now, I visualize it [as] a liberated territory, a bastion of liberty in the statist sea, based on the basic libertarian doctrine that a person has a right to do anything he wishes so long as he doesn’t harm anyone else.”

Gaytopia would be a starting point. “I visualize [ALF] growing into a national organization,” Jackson wrote. “The liberation of Alpine for Gays will be only its first objective; it will go on to liberate other cities, counties and states for the people—counties for Indians, counties for Hippies, counties for any oppressed people who want to free themselves from the oppression of the ancient regime. The Alpine Liberation Front can become a major thing in the history of the nation.”

But Jackson worried about the effects of the publicity surrounding the project. He later said he feared it was making the project “appear unreal.”

Back in the High Sierra, 5,500 feet above sea level, residents of Alpine County were busy forming committees of their own. At a daylong meeting at the single-story courthouse in Markleeville, their county seat, on Thursday, November 12, Hubert Bruns, the chairman of the board of supervisors, called the proposed takeover “the most crucial problem any county has faced, perhaps, since the Civil War,” and compared GLF’s tactics to Hitler’s. “Possibly these people are victims of persecution, and we will help them if we can,” Bruns said, “but not by allowing them to take over Alpine County. We hope to convince the people in Los Angeles this is not a good place for them to live.”

Nor was Carl McIntire’s proposal any better received in Alpine County than GLF’s. Many residents now felt they were caught between two opposing forces far beyond their control. Their home had become an early battleground in what would come to be known as the culture wars.

Rumors were going around that rich homosexuals were already gobbling up property in the county, hoping to open “gay resorts.” Some residents wanted to invite Joe Conforte, the owner of the notorious Mustang Ranch brothel across the border in Sparks, Nevada, to open a branch in Markleeville, presumably to somehow counteract the influx of gays.

Residents formed committees that day. One would prepare emergency legislation to dissolve the county by merging it with neighboring El Dorado County if necessary. Another would “prepare a plan for maintenance of law and order.”

Chris Gansberg, the chief of Markleeville’s volunteer fire department, was confident that the county’s harsh winter weather, when temperatures of -20° Fahrenheit were not uncommon, would deter the would-be settlers. “An invasion by 500 people in January would create a land office business for the undertaker,” Gansburg said. “It could not be done with any degree of success.”

An NBC News crew covered the meeting, and a very serious report from tiny Markleeville aired the following night on the NBC Nightly News amid updates on the Vietnam War and student protests.

The anticipation of colliding worlds would come to a head on Thanksgiving Day, when an advance party from the Los Angeles office of the GLF arrived. Steve Beckwith, Rod Gibson, and June Herrle had made the seven-hour drive from Los Angeles to the remote mountain town near the Nevada border to “test the temperature and savor the landscape and report back to [GLF] on conditions.” They were accompanied by a handful of journalists.

Wrapped in scarves and heavy coats against the late autumn chill, with buttons reading alpine or Bust pinned to their lapels, Beckwith, Gibson, and Herrle—two hirsute men and a small woman with short hair—collected soil samples and recorded the temperature. At Egger’s, a general store and Chevron station, they bought a loaf of bread, a bag of potato chips, and a bottle of wine for lunch. Besides Egger’s, the visitors could glimpse a forlorn hotel with a restaurant and bar, a coffee shop, and a post office—and not much else. The general store’s owner, Gus Egger—who was also a county supervisor and had lived in Markleeville since 1947—was unperturbed by his unusual customers, though he wondered how they’d make a living once they got to Alpine County.

Beckwith, Gibson, and Herrle posed for photographs on the steps of the county courthouse that would, they hoped, soon be the seat of the world’s first all-gay government. Across the street, they held an impromptu press conference in a small memorial plaza with a fountain that commemorated a former county sheriff. Perhaps they noticed the promise of its inscription: “Devoted to Duty—Loyal to Community—Friendly to His Fellow-Men.”

“We want to show the local residents that homosexuals are just plain people like everybody else,” Beckwith told the reporters.

The next day, Beckwith, Gibson, and Herrle met with Alpine County Sheriff Stuart Merrill in front of Egger’s. Beckwith proposed a meeting with local residents, but Merrill was having none of it. He had already tired of the publicity the project was attracting. “Absolutely not,” the sheriff said. “The people of Alpine County haven’t time to attend any meetings. They are tired of being pestered by you people.” It is possible Merrill also had not been pleased to hear about the plan to have a gay sheriff.

“You’re not going to tell us what to do!” Beckwith shouted in response. “We want to come into this county peacefully, but we are going to come in, no matter what you say.”

GLF had scheduled the visit over the long Thanksgiving weekend partly for the symbolism. These young, radical homosexuals saw themselves as modern-day pilgrims, intent on escaping political and social persecution and eager to find a new land of independence and opportunity.

The scheduled start date of the migration was January 1971. Alpine County held its collective breath. Then a mammoth blizzard dumped more than three feet of snow in the mountains, temporarily cutting the town off from the outside world.

McIntire’s minions did not show up to try to stop the Alpine pilgrims. In fact, his hold on his enterprises was slipping. In a year’s time, McIntire lost his appeal of the FCC’s revocation of his radio station’s license. His empire crumbled, and his ministry never recovered.

But the new year brought a far darker obstacle. There had been threats, including, reportedly, by the Ku Klux Klan, but the real danger to the project ended up coming from within. Gibson, one of the Thanksgiving Day pilgrims to Markleeville, discovered evidence that the upper echelons of GLF in Los Angeles had never had any intention of providing the continuing support the project would need to be completed. It was all a lie, a clever stunt. Gibson was furious when he learned that “an elite group of [GLF] members”—namely Kight and Kilhefner—were simply using the project to generate publicity and were in effect lying to the gay community as well as the establishment press while leaving to “those who thought the project to be valid . . . the monumental task of making it come off.” Gibson wrote in a letter exposing the hoax, “The ends will never justify the means when it entails using peoples’ hopes and dreams.”

Getty Images

Jackson who had literally dreamed up the idea, was devastated. He had been in almost constant contact with Kight, never imagining that he Kight had no intention of implementing the plan. He felt betrayed, and he never forgave Kight for leading him on.

“Kight didn’t want to risk ruining the scheme if he let Jackson in on his real intention to use Alpine County solely as an agitation and propaganda tool,” explains Kight biographer Mary Ann Cherry in Morris Kight: Humanist, Liberationist, Fantabulist. “Their relationship never recovered from the betrayal that Jackson experienced when Kight backed away from the Alpine dream . . . Kight bruised more than a few personalities and made some serious enemies on the road to gay liberation.”

Kilhefner, now 82 and still active in the gay rights movement in Los Angeles, admits the ploy, describing the Alpine County project today as “agitprop.”

“We weren’t doing it because we were serious,” he says. “We would do things to get the Man’s attention so we could get our issues out there. It was a serious attempt to get into the media some knowledge of the gay movement, that gay people were everywhere.”

Kilhefner explains that the announcements at the press conference on October 20, 1970, were complete balderdash—he and the others present just made it up as they went along. “The press conference was a Potemkin village,” Kilhefner says. There had never been 479 volunteers lined up to move to Alpine County, much less doctors, lawyers, and teachers. As far as he was concerned, there would be no migration on January 1, 1971—or ever. It was an unexpected turn when the project took on a life of its own, and GLF’s rank and file began planning for the move in earnest. And in order to maintain the ruse—to keep generating publicity—GLF’s leadership had to keep the rest of the group in the dark. “It was meant as political theater,” Kilhefner says, “but some people took it seriously.”

Weathers, one of those people, now recalls how “people felt used” when they found out the project was phony. “Many of us were upset that it had been fake,” she says.

“I feel like the Alpine stunt was a publicity stunt a bit along the lines of a Lee Atwater dirty trick that went too far,” Del Whan, who joined GLF in early 1970, said. “Many gay people took the plan to set up a gay county seriously, however, and were very upset when they eventually realized that Morris was just making waves to stir up public attention for gay civil rights.” She worries that the Alpine County project overshadows GLF’s genuine accomplishments, such as organizing the first Gay Pride parade in Los Angeles.

Once the hoax was exposed, planning for the Alpine County project came to a screeching halt. Though true believers may have been able to follow through without their leadership, the effort was demoralized. The hoax may have hastened the group’s demise. Disenchanted members drifted away, and by the end of 1972, the Los Angeles Gay Liberation Front was no more.

But Kilhefner has no regrets. “I saw immediately it probably would go nowhere because the 10 to 12 people involved were largely talkers not organizers, and they had no driven, resourceful, fire-in-the-belly leader. Both Morris and I kept those thoughts to ourselves and never criticized the Alpine Project in any way, always taking the position that we support you in your attempt to make it happen; however, never did we put any time or effort into it. And it died a natural death.”

As a publicity stunt, however, Kilhefner says the Alpine County project was spectacularly successful. “It opened a lot of people’s eyes. Because we weren’t begging for acceptance. What we were saying was, ‘Fuck that shit. We’re here, we’re queer, we’re part of the society, and we’re becoming politically aware. We’re fighting back. We won’t take it anymore.’ That’s the legacy of the Alpine County project.”

In Alpine County itself, if the nuances were unclear, the residents could see their new neighbors were simply not showing up. Sheriff Stuart Merrill told a reporter, “I think they have given up.”

Perhaps the most notable twist, though, was that the position of many in Alpine County had changed. When still preparing for the influx, a committee had been formed to “see to the Gays’ welfare.” “Homosexuality is as old as heterosexuality,” Ruth Jolly, the county health officer, had commented. “That it is undesirable may be argued, but to talk of invading this county is sickness.”

Some residents also pointed out that an influx of new residents, whatever their sexual orientation, would raise property values, increase the tax base, and boost local businesses. “I hope they come,” one merchant said. “Hell, 500 more people up here, and my business would triple. Of course, I will sell to them. I’m open to the public aren’t I?” Several prominent citizens, including the school superintendent and the county welfare director, ended up expressing support for the project. Gibson, by the end of his Thanksgiving mission, had even felt “re-inspired” by positive interactions.

Following up on the abortive Alpine County project in 1975, the Los Angeles Times reported that the endeavor had “raised the consciousness of at least one resident”: Hubert Bruns, the county supervisor who once had likened GLF’s tactics to Hitler’s. “I don’t think they’re as dangerous as we thought at the time,” Bruns told the paper. Bruns also said he “had come to realize there were probably homosexuals already living in Alpine County,” though, he added, “none are ‘out of the closet’ that I know of.” The strangest fact about the relocation project may be that it really could have worked had it not died of a collective broken heart.

Today, the population of Alpine County is about 1,100. It’s still California’s least-populous county, but it has become decidedly more gay-friendly than it was in 1970.

After the Alpine County project fell apart, Jackson turned his attention to creating a gay utopia in a tiny San Diego County town called Bankhead Springs. But that project, known as Mount Love, unraveled, too. Jackson’s byline disappeared from the pages of the underground papers in the mid-1970s. He dropped out of sight. “He just kind of disappeared from the organized, radical gay community,” Kilhefner says. “I consider him one of the pioneering warriors of early Gay liberation—an essential voice. I honor him.”

Published in partnership with Truly*Adventurous, trulyadventure.us

RELATED: The Damron Address Book, a Green Book for Gays, Kept a Generation of Men in the Know

Stay on top of the latest in L.A. food and culture. Sign up for our newsletters today.