It all started with a distinct ping. And by distinct ping, we mean a Grindr message.

“It was on this app that, for the first time ever, some white guy greeted me by saying, ‘Hola papi,'” John Paul Brammer writes in his memoir, out Tuesday, that was inspired by this message and his advice column of the same name.

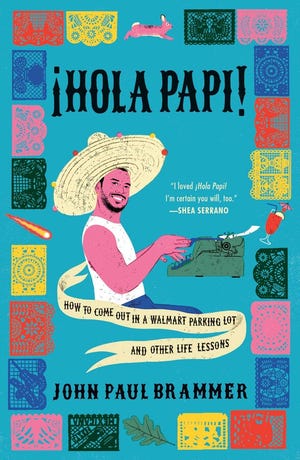

The mixed-race Mexican-American writer created the column several years ago and channeled the format into an essay-filled memoir “¡Hola Papi! How to Come Out in a Walmart Parking Lot and Other Life Lessons” (Simon & Schuster, 206 pp.). Expect, above all else, vulnerability.

Menacing middle school bullies who prompt Brammer’s suicidal thoughts. A “one that got away”-style love story. And as the sub-headline in the title suggests: Coming out in a Walmart parking lot. Consider it par for the author’s meandering-but-methodical course.

“I love the idea of portraying what’s going through someone’s mind, the moment they make a decision, or the moment that they experience an emotion,” Brammer, who is from rural Oklahoma but now lives in Brooklyn, New York, tells USA TODAY. “I just really like putting those things into words, because I think that’s the most ambitious, beautiful thing that language can really do, it can sort of put someone else into the experience or the life of someone else. And I like using my own life to that end, because I think that’s so intimate.”

Hmm:Is coming out as a member of the LGBTQ community over? No, but it could be someday.

How the column ¡Hola Papi! became a memoir

¡Hola Papi! has lived at a series of different companies and publications including queer dating app Grindr (yes, the irony), Condé Nast, Out Magazine and now at Substack (and is syndicated in The Cut).

“That’s not so much a reflection of my commitment issues, which I do have, but more of a reflection of instability in the media world,” he says.

Brammer wasn’t sure if letters would ever come in when he launched the column, but oh boy, did they.

A sampling of recent ones: “How do I stop comparing myself to other people?” “Papi, am I secretly hideous?” “Papi, can I be proud of where I’m from? Even if it sucks?”

That said, the column is known to be “notoriously unhinged,” Brammer says. Nothing beats his favorite letter from a man whose boyfriend was pretending to be Colombian. “I reread it three times thinking, ‘How did I get such a gem in my inbox?'” he says with a laugh. (He advised they break up.)

Brammer structured his memoir as a series of advice columns to pay tribute to the column.

“I’ve always thought of it as a vehicle for my writing, and not my biggest aspiration in life or anything, but I wanted to pay homage to the format and the medium, because I’m so thankful for it and there’s no guarantee that I would have found the readers that I did,” he says.

Oooh:The gay royal romance novel is having a moment: ‘Everybody deserves a happy ending’

On writing about your life: ‘You should know how you feel about it, but you often don’t’

Brammer sticks to the old adage: Write what you know.

“If I’m writing about something, it pretty much means I’m at peace with it,” he says.

“I’m not one of those people – and I really admire these people – who haven’t quite figured out how they feel about something and they use writing to help them figure it out, almost like in the process of writing it so it helps them realize, ‘Oh, okay, these are my feelings.'”

He tenses up otherwise. “I find it difficult to write about things that I haven’t quite figured out or that I’m still struggling with or that still bring me anxiety or fear,” he says.

To that end, the book offers zoomed-in snapshots into Brammer’s life as opposed to a panoramic view. He details one incident of sexual assault, for example, but chose to not include an incident where the first official man he started dating raped him.

“I wanted to write that story so badly but at the end of the day, I find him to be such an uninteresting person,” Brammer says. “And I find that whole experience was really heavy and intense, yes, but I couldn’t quite feel the emotional intensity I was looking for that I needed to write something about it.”

Brammer joked with his friends about it a few days later, then realized he needed to take it seriously – only to bury it, and once again revisit it years later.

“It’s such a weird, interesting activity to look back at the facts of your own life, which, obviously, you’re the expert, you live through it, you should know how you feel about it, but you often don’t,” he says. “Social trends and conversations and culture can re-contextualize how you see the facts of your own life. And that’s something that’s very uncomfortable to acknowledge because we want to feel like we have a good handle on the things that have happened to us, and that we know our own story. But with new information comes reshuffling of the narratives. And that’s often a painful process, it’s often very fraught.”

Please and thank you:10 new LGBTQ books to celebrate Pride Month: Gay ‘Great Gatsby,’ ‘Queer Bible,’ more

Brammer is already at work on his next book

Brammer misses his pre-pandemic writing routine. And we may have missed out on more quality quillwork from the author.

“Not being able to work in coffee shops has – I’m not going to say that it’s robbed this country of some cultural treasures, but maybe so, because I haven’t been able to write the way I have been for a year and a half now, because I just can’t sit my butt in a coffee shop,” he says.

Brammer is starting on his next book now, which is a fictional take on a chapter that didn’t make it into the memoir about his first gay house party when he was still coming to terms with himself.

“It’s all coming together a little bit right now, just throwing words to a Google doc and seeing if they stick,” he says. “If it works, I’d be really happy. If it doesn’t, I’ll move on to something else.”

Our advice? Devour whatever Brammer cooks up.

If you are a survivor of sexual assault, you can call the National Sexual Assault Hotline at 800-656-HOPE (4673) or visit hotline.rainn.org/online and receive confidential support.

The Trevor Project helps LGBTQ+ people struggling with thoughts of suicide at 866-488-7386 or text 678-678.

The LGBT National Help Center National Hotline can be reached at 1-888-843-4564.

If you or someone you know may be struggling with suicidal thoughts, you can call the U.S. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255) any time day or night, or chat online.

Crisis Text Line also provides free, 24/7, confidential support via text message to people in crisis when they dial 741741.

Noted:What if ‘The Great Gatsby’ was unquestionably queer? This author went there