The focus for years in the state’s fight against substance abuse has been on illegal and prescription opioids, but a legislative committee on Tuesday heard from experts that the use of stimulants, particularly methamphetamines, has been quietly on the rise without a system in place to adequately respond.

The Joint Committee on Mental Health, Substance Use and Recovery held a hearing to solicit feedback from experts in the field on the use of stimulants and the state’s preparedness to respond.

After a year of living through a pandemic, the opioid crisis has not gone away, but not every overdose death can be blamed on opioids, with an increasing number of tragedies related to stimulants or the mixing of the two types of narcotics.

“These issues are now more pronounced than ever,” said Rep. Adrian Madaro, an East Boston Democrat and the co-chair of the committee alongside Sen. Julian Cyr.

Fentanyl continues to drive overdose deaths in Massachusetts, according to the experts, but increasingly the opioid is showing up in non-opiate narcotics, like cocaine and meth. The use of meth is also more prevalent among gay and bisexual men, according to researchers, and can lead to spikes in HIV and other health issues if not addressed.

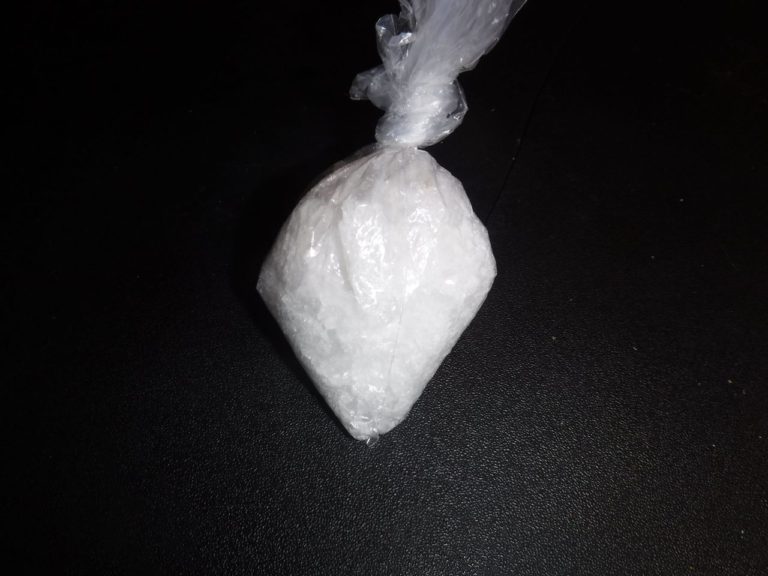

Cocaine and crack seizures have actually declined in the region over the decade from 2000 through 2019, but methamphetamine seizures by law enforcement have climbed between 1,700 and 2,900 percent.

“It’s huge,” said John Eadie, project coordinator for the federal High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas programs.

The Department of Public Health reported that over the first six months of 2020 cocaine was present in 31 percent of the 1,878 opioid related overdose deaths and amphetamines were present in 6 percent of cases.

Eadie said data on seizures is used by researchers to track supplies of a particular drug, and has been shown to have a very close correlation with overdose deaths in a particular region. While overdose data can lag a year to 18 months, Eadie said seizure data can be obtained through the local HIDTA office much more quickly and be used to warn hospitals and first responders about potential spikes in usage.

He encouraged Massachusetts to set up a system with the Northeast HIDTA to track seizures as Vermont is already doing.

While opioid prescription rates declined in Massachusetts in the second half of the last decade and the state ranked 20th of the 26 states reviewed by HIDTA for opioid prescriptions per capita, Massachusetts ranked first among those same states for stimulant prescriptions.

“They’re riding right along the wave with meth and the wave on cocaine,” Eadie said.

From 2010 to 2019, the number of stimulant prescriptions being written climbed from about 210 to 350 per 1,000 people.

“You’ll want to take a hard look at whether that is due to sudden radical changes in health and the medical diagnoses of the population of your state or whether more likely that is related instead to diversion into illicit use to match the methamphetamine use increase in your area,” Eadie said.

Other issues flagged for legislators included training for police, medical technicians and other public safety personnel and treatment programming designed for stimulant users.

James Cormier, drug intelligence officer for the New England High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area and a former police chief in Reading, said responding to a call for someone under the influence or overdosing on an opioid is very different than if someone had used a stimulant like meth.

“One of the things that we’re going to need to do is prepare public safety people for the increase in stimulants. It’s going to be completely different than what we’ve seen with opioids and it’s important that we get ahead of it,” Cormier said.

Deirdre Calvert, director of the Bureau of Substance Addiction Services at the Department of Public Health, also told the committee that many of state’s substance use treatment programs have been designed for people with alcohol or opioid addictions, but may not be appropriate for people detoxing from a stimulant who needs a different behavioral therapy approach.

“If you’re a polysubstance user or a stimulant user, what I’m hearing is we just don’t have interventions that are going to make a difference,” Cyr said.

Calvert said the federal government recently approved the use of substance use treatment funding for stimulants as well as opioids, which will make a difference. She said the state hoped to expand the use of fentanyl strips for users of stimulants to be able to tests for the presence of the lethal opioid.

“It’s trying to turn the Titanic on a dime,” she said.

Calvert said that 34 percent of admissions into Bureau of Substance Addiction Services programs report using stimulants, with only 7 percent indicating that as their primary drug of choice.

From February 2020 to September, 2020, people admitted to substance treatment programs reporting the use of cocaine increased from 40.3 percent to 50.5 percent, from 42.2 percent to 54.4 for crack cocaine use and from 33.4 percent to 39.1 percent for methamphetamine.

“Based on the data and recent reports, stimulant use and overdoses are occurring with the increasing infiltration of fentanyl in the non-opiate drug supply,” Calvert said.

California State Sen. Scott Weiner, who represents San Francisco and chair’s the California Senate’s mental health caucus, said the use of methamphetamine has been a problem on the West Coast, and in San Francisco, for a long time.

“Opioids understandably have gotten an enormous amount of attention and resources given the train wreck we have seen from Oxycontin and other drivers of this crisis and that is terrific, but I don’t think meth has gotten the focus that it needs,” Weiner said.

Weiner said in San Francisco political leaders like himself and activists are working to open meth sobering centers like the city uses for alcohol to keep people that don’t need to be in the emergency room out of hospitals.

He said he’s also working to pass legislation legalizing safe drug consumption sites, an idea that has been controversially debated in Massachusetts, and to improve private health insurance coverage for mental health and substance use treatments.

Cyr said he hopes the Legislature this session can revisit a comprehensive mental health parity law passed by the Senate last session that stalled as the pandemic arrived.