Ruth Coker Burks never intended to be an advocate, activist or even an angel. She just wanted to do the right thing.

“Oh, I’m no angel,” Coker Burks, 62, told TODAY. “I’m just a person.”

But that’s how her legacy has been defined when one fateful day in 1986, at just 26 years old, she was visiting a friend, Bonnie, at a local hospital in Little Rock, Arkansas, who had been suffering from oral cancer. Bonnie had her tongue removed, and Coker Burks was her interpreter. This was their fifth extended hospital stay, but this time there was something different. Out of the corner of her eye, Coker Burks spotted a door down the hall with a bright red tarp across it, food trays piled up outside and a group of nurses at the door, unwilling to go in.

“I had been in hospitals a lot of times and so I thought that was really bizarre,” she said of the biohazard red door. “The nurses were literally drawing straws to see who would go in and check on this person. They would draw straws and it’d be best out of three, and then they didn’t like that and so then it’d be best 2 out of 3 and then no one would end up going in to check in on this person. They just walked away.”

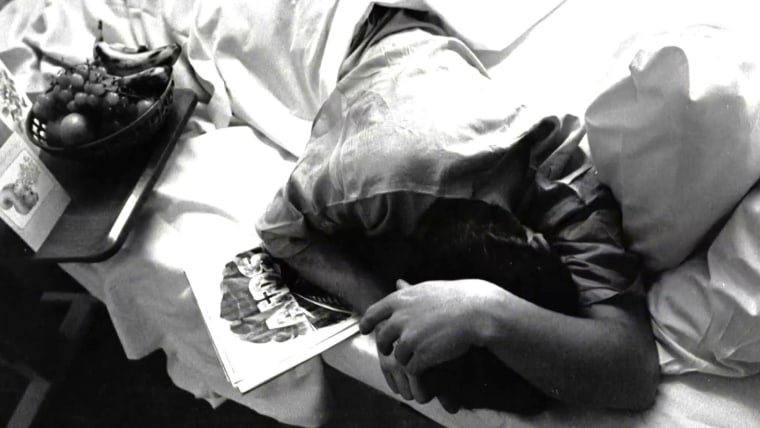

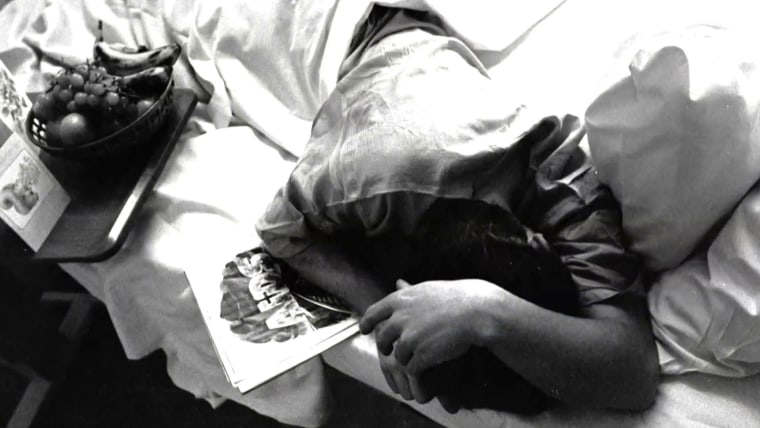

Her curiosity overcame her, so when the nurses left their stations, she snuck into the room to see who was there. She struggled finding the person at first, who was so frail and near death, she couldn’t even tell he was in his bed. “I had to look for him,” she explained. “I thought maybe he was in the bathroom. You couldn’t tell the difference between him and the bedsheets. It was just horrible.”

This was the first time she would encounter a person dying from AIDS, but it wouldn’t be the last. Over the next decade, Coker Burks would care for over 1,000 gay men dying of the disease who were abandoned by their families.

In honor of LGBTQ Pride Month and the 40th anniversary of the beginning of the HIV and AIDS epidemic in 1981, TODAY had the opportunity to talk with the accidental activist to look back on her incredible story that above all else, shows what happens when someone overcomes fear for love and life.

‘Nobody’s coming’

Prior to that fateful hospital visit, Coker Burks had heard rumors about the then-unnamed disease when visiting her hairdresser cousin in Hawaii. A devout Christian, single mother of one and real estate agent working in the timeshare industry, Burks pretended to know a lot more about the gay community than she actually did.

“Oh honey, don’t worry about that,” her cousin told her about the disease soon to be labeled HIV and AIDS. “Just the leather guys in San Francisco are getting that.”

But it was that day while caring for her friend Bonnie when she encountered AIDS for the first time in person — and knew it wasn’t just affecting the “leather guys” in California.

“I went over to the bed and I didn’t know what to do but I took his hand and I said, ‘Honey, what can I do for you?”’ she remembers of the fateful encounter. “He looked up at me and he didn’t have any more tears to cry. He was so dehydrated there was nothing left to produce any tears. But he looked up at me and he said he wanted his mama.”

Coker Burks felt this was something she could do: Get his mother to come to the hospital and then go back to Bonnie and get back to minding her own business, something she admits she’s never been “very good at doing.” But what she quickly realized is that his mother knew where he was, and she had no intentions to visit him.

“I went over to speak with the nurses, and they backed up like I had them at gunpoint,” she said. “They said, ‘You didn’t go in that room, did you?’ Well yeah, I noticed that y’all weren’t going in. So they started fussing at me and then they just backed up even more.”

She recounted what they said to her: “His mother’s not coming. Nobody’s coming, he’s been in this hospital for six weeks, nobody’s been here and nobody’s coming and don’t you go back in that room.”

Well, Coker Burks didn’t listen.

The man’s name was Jimmy, and his experience was more common than not. Many gay men who became sick with HIV and AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s were shunned by their families, abandoned and left to die alone.

Coker Burks tried calling Jimmy’s mother numerous times, but each time his mother refused to take the call. After a few attempts — and a heated threat to put his obituary in her local newspaper — his mother answered her questions. “My son died years ago when he went gay,” she told Coker Burks. “I don’t know what thing you have at that hospital but that’s not my son.”

Coker Burks knew that was the best she was going to get out of her, so she stayed by Jimmy’s side until he died the next day.

“I thought he would be the only one and I would get back to going to church every Sunday and you know, being a good Christian living the best life I could,” she said. “I had a young daughter, her father and I were divorced, and I was just trying to be the best mother and set the best example I could for her. I thought I’d just go back to that.”

But after leaving Jimmy’s hospital room after he passed, she learned that the homophobia these men experienced lived on well after their final breathes. The nurses said the body needed to be dealt with, and that the hospital’s morgue didn’t want him because they were scared the other bodies would get contaminated. (She jokes, “Of course, you don’t want a dead body contaminated with anything, especially imagination.”)

The nurses insisted she take him. It was difficult to find a funeral home who would take Jimmy, but after many attempts she was able to find a place that would cremate him and she buried him with her own father. With her daughter Allison by her side, they got a cookie jar for his ashes, dug a hole above her father’s coffin and planted flowers to mark the spot.

“We had a little do-it-yourself funeral, said the Lord’s prayer, put the flowers and a big rock on top of him and we left,” she explained. “And I thought, you know, that’s going to be the only person I ever have to do this for. I mean, who would think you would ever have to do it twice in your life, right?”

She went back to selling timeshares. Then more and more local men in Arkansas began getting infected with HIV and becoming sick with AIDS. Nurses started giving out Coker Burks’ number to their patients, telling them, “There’s a crazy woman in Hot Springs who isn’t afraid of you.”

No matter what, Coker Burks answered their calls. She buried 39 others in her family’s cemetery, and cared for hundreds more for over a decade.