Part two

Growing pressure for more reform

From late 2014, therefore, the incongruous situation was that there were two possibilities for same sex partners to form legal unions, but only one, marriage, for opposite sex partners. This was not the end of the story, though. After a legal challenge by an (opposite sex) couple who wished to have a civil partnership, the Supreme Court ruled that the Civil Partnership Act 2004 – which only applies to same-sex couples – was incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights. This judgement prompted the government to pass an Act[1] instituting this new, second, form of civil partnership, the first of which took place on 31 December 2019.

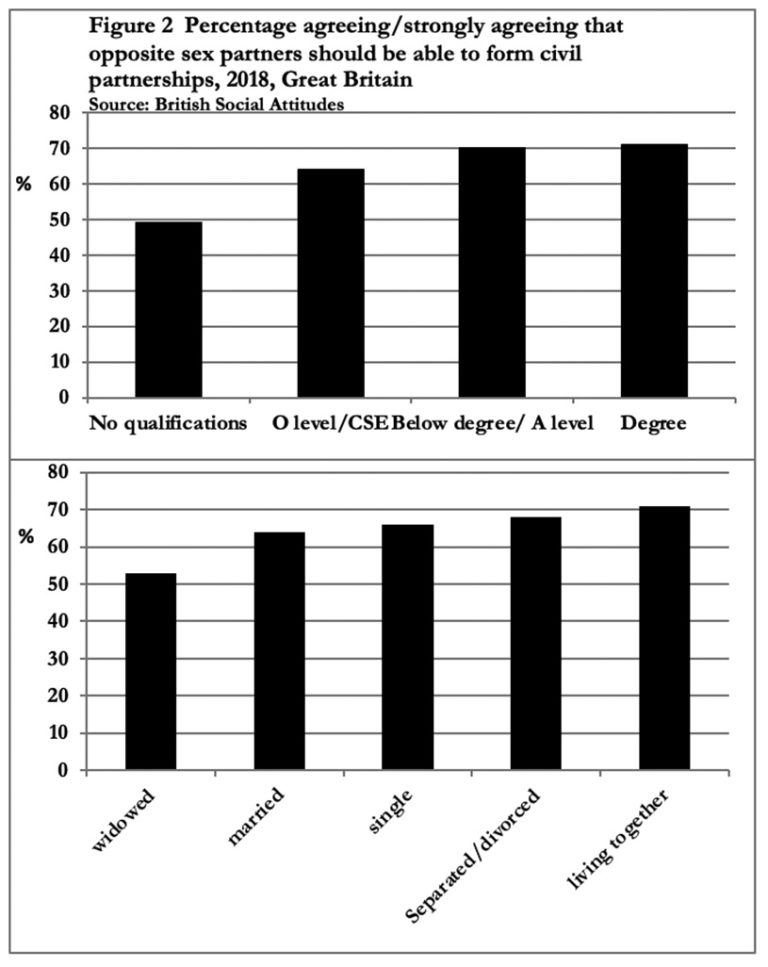

Around the time of this judgement, June 2018, the British Social Attitudes survey[2] asked a question on whether opposite sex couples should be able to form a civil partnership. The results are shown in Figure 2 and show substantial and widespread support for opposite sex civil partnerships. Respondents with higher levels of education and those living together, ie cohabiting with a partner, were the most likely to support the availability of the new civil partnership, whilst those with no qualifications, the widowed, and those identifying with a religion, were the least likely. The survey also found that a higher level of education, and no religious affiliation, were the factors most closely associated with explaining support for opposite sex couples.

Although, recently, a large majority, almost 70%, of the public believe that same sex relations are not at all wrong – see Figure 1 – there nevertheless remains variation in opinion on the matter; not only by age and religious belief, but also, with a distinct differential, according to one’s political opinions in a social sense, that is, according to whether libertarian or authoritarian in outlook. Figure 3, again derived from data from the British Social Attitudes survey,[3] indicates that, at every age, those with a libertarian outlook are much more likely to believe that same sex relationships are not wrong at all, compared with those of an authoritarian viewpoint. This differential – which widens with older age – accords with the libertarian belief that personal freedom should be maximised, while authoritarians prize order and tradition. It is interesting that in the youngest age group, 18 to 24, there is scarcely any difference in attitudes, which no doubt develop and differentiate with increasing experience of life.

The present position

The present situation is complex; currently there are two options, civil partnership and marriage, for both opposite sex couples and same sex couples. Symmetry has eventually been achieved, and with it, a measure of equality. At least one aspect exists, though, where there is no symmetry – and perhaps no equality, either. That is with the option of converting one form of legal union into another. Unlike the case for same sex civil partnerships, with an opposite sex civil partnership there is no right to convert it to an opposite sex marriage, at least not for the time being. In addition, the most recent consultation exercise in July 2019,[4] on implementing opposite sex civil partnerships, included consultations on all the possible conversions. The government stated that they had considered conversions from opposite sex civil partnerships to marriage but, while not ruling them out, sounded distinctly unenthusiastic. Administrative complexity amongst other reasons was cited, and also that couples could have married anyway if they had so wished.

On the other hand, for the reverse transition, the government’s guarded provisional view was to allow opposite sex married couples to convert their marriage into a civil partnership. Even so, it was proposed that such conversions, as well as the existing ones – from same sex civil partnership to same sex marriage – might be time-limited, ie both options finishing on a given future date. This one additional conversion option was justified on the principle of allowing conversions of only those relationships which had previously been unavailable. The government’s apparent reluctance to extend the conversion options from marriage to civil partnerships may have been partly influenced by religious views that such conversions implied a repudiation of marriage vows.

The results of the consultation, and the government’s response, have not yet been published, although, of course, opposite sex civil partnerships have since been legislated, partly as a result of the Steinfeld and Keidan case[5][6] prompting the government to address the issue of inequality.[7] This was the third new formalised relationship which has been legislated during recent years, and there have been some surprises in the numbers who have taken up the new options, as will now be explored.

Figure 4 shows the available monthly numbers of the formation of: same sex civil partnerships; same sex civil partnership conversions to same sex marriages;[8] and same sex marriages. (There were 167 opposite sex civil partnerships registered on 31 December 2019, the first day possible, but no further counts are available). It may be seen that just after the introduction of same sex civil partnerships in December 2005, there was a surge of some 13,000 in the first 9 months of 2006, roughly 1,400 per month, undoubtedly released from a built-up reservoir of all those who were previously unable, but wanted, to form a legal partnership. After that initial swell, the numbers settled down into a seasonal pattern – much like that for traditional marriages – which was particularly regular (see light grey line). Then in March 2014, same sex marriages became possible (see start of black line), and it is remarkable how almost immediately and completely they took over the monthly numbers and seasonal pattern of the hitherto civil partnerships which quickly faded to a very small, fairly constant, monthly number of just under one hundred. It is noteworthy that, comparatively, civil partnerships almost completely lost their seasonality, suggesting that, after March 2014, those choosing civil partnerships, instead of same sex marriages, have differed in their characteristics, and possibly their views on civil partnerships, too. More likely is that some same sex couples tended to want a small private celebration, whilst those wanting a large outdoors gathering, which would be better in the Spring and Summer months, tended to prefer same sex marriages as soon as they became available.

Also shown in Figure 4, as a dotted line, are the numbers of same sex civil partnership conversions to marriages. (Of course, couples who converted their civil partnership are counted twice in Figure 4; once initially when they formed their civil partnership, and again, later, when they converted it; however, the two counts almost certainly were not both in the same month.) Again, it may be appreciated that once couples were able to convert their civil partnership into a same sex marriage, a deluge did so; there were 2,400 conversions during December 2014, the first month possible. Just as the advent of civil partnerships released an untapped number wishing to form a legal union, so the newly available option of civil partnership conversions to marriage released a backlog of those wishing to marry rather than continuing to be civil partners. Interestingly, once the initial large peak of conversions had taken place by April 2015, a seasonality can be seen to have emerged over the following period, albeit superimposed on a diminishing trend. With the introduction of same sex marriage, a study[9] found that those in same sex unions fell into three groups concerning their attitude to civil partnerships: a stepping stone to equality (marriage); legal recognition of a freer form of relationship; and those who were ambivalent. However, the principle of equality underlay all opinions.

Between January 2006 and December 2017, there were approximately 63,000 civil partnerships formed, and from December 2014 till December 2017 there were about 14,000 conversions, or roughly 23% of all those eligible. Of course, not all of those in civil partnerships necessarily wanted, or currently wish, to convert their civil partnerships into marriages; this very rough estimation is solely intended to show that there is scope for more conversions, although, from the graph, it may be appreciated that the number of such conversions had reduced considerably by the end of 2016. The fact that a large proportion of civil partners have not converted their partnership may well reflect their contentment with the new status. Alternatively they may have been unaware of the facility to convert, or even (erroneously) considered themselves either married or ‘as if married’.

Men couples currently form almost two thirds of new civil partnership formations, and women one third, whereas, before the advent of same sex marriage, the numbers of men-couple and women-couple new partnerships were almost exactly equal. In contrast more women couples than men couples enter same sex marriages, so that perhaps men marginally prefer same sex civil partnerships and women marginally prefer same sex marriages. (A possible explanation may concern commitment; women seek stronger commitment from their partners than men, and marriage is seen as placing greater emphasis on commitment than civil partnerships.) In addition, about one quarter of women forming civil partnerships were previously divorced or had their previous partnership dissolved, compared with only one tenth of men, which accords with dissolution results which follow.

Dissolutions and divorces

Inevitably, there have been dissolutions of same sex civil partnerships since shortly after their inception, and it is instructive to compare the dissolutions of men civil partnerships with those of women. For most of the period during which civil partnerships have been possible, there have been more men couple civil partnerships formed than those of women, and in fact, in the first full year of civil partnerships, 2006, there were 3,000 more civil partnerships between men than between women, that is, half as much again. In general, in most months since the start of civil partnerships, the number of men couple civil partnerships formed has exceeded those of women, although for a few years, from 2010 to 2013, there were slightly more women couple partnerships than men in the Summer and Autumn months, June through to September. This exception was only temporary, and from 2015, the monthly numbers of men couple civil partnerships formed have been approximately double those of women.

In contrast, the picture for dissolutions is very different; there being consistently larger numbers of women couple civil partnerships being dissolved than those of men, as is shown in Figure 5. It is apparent that, for both men and women, the numbers of dissolutions rose quarter by quarter, undoubtedly reflecting the growing pool of civil partnerships liable to be dissolved, as new civil partnerships were being formed, constantly adding to all those formed earlier. After mid-2016, though, the numbers of dissolutions started to fall, possibly due to the total number of existing civil partnerships having fallen with a large number having converted their civil partnerships to marriages, and also with the quarterly number of new partnerships being formed having reduced considerably compared with formerly (see Figure 4), through same sex couples marrying, rather than becoming civil partners.

A rough picture can be obtained of the comparative dissolution patterns of men couple and women couple civil partnerships, by comparing the total number of dissolutions up to a given point with the corresponding total number of civil partnerships having been formed up to the same point. By expressing the cumulative former number as a percentage of the cumulative latter number for each point, one can obtain an approximate measure of the relative dissolution rates between men and women. (In fact, in practice, the cumulative number of dissolutions was related to the cumulative number of formations up to one year behind that for dissolutions, because a dissolution cannot be granted within the first year of the civil partnership.) The results are depicted in Figure 6 where it may be seen that the proportions for women couples dissolving their civil partnerships are consistently larger than those of men. A similar kind of approximate analysis was undertaken using annual numbers of same sex marriages and the related divorces, and again, the cumulative proportion of divorces of same sex marriages for women consistently exceeds that for men.

Ideally, definitive analyses would involve relating the numbers of dissolutions/divorces by the duration of partnership/marriage to the corresponding numbers of civil partnership formations/same sex marriages in each year to obtain the proportions dissolving/divorcing at each duration of partnership/marriage. These provisional, general, results should be confirmed once such fuller statistical information becomes available. Fortunately, the results in Figures 5 and 6 are based on data during a relatively stable period before the Covid pandemic, and also before the Divorce, Dissolution and Separation Act 2020 replaces the present divorce law.

The results shown suggest a similar differential in both dissolutions and divorces, with larger proportions for women than men. It is interesting to note, too, that, in opposite sex marriages, a larger proportion of women petition for divorce than men.[10] Possibly women are more likely than men to take the initiative to end their relationship if it is unsatisfactory, failing, or finished. Possibly, too, women generally have more household and other roles than men, with a correspondingly larger chance of disagreement over division of labour. Overall, the reasons for relationship breakdown amongst same sex couples have been found[11] to be similar to those in divorce, such as infidelity, particularly disappointing to those who optimistically expected their newly legislated relationships to be more reasonable and stronger than traditional marriages.

Discussion and conclusions: a ‘non-family lawyer’s’ view of the possible future course for civil partnerships and marriages

Although one might conclude that much has been achieved (provided one is not overwhelmed by the complexity), a number of loose ends remain (adding to the potential total complexity). Much depends on the government’s response to the latest 2019 consultation.[12] Perhaps the most immediate question is whether, with the latest opposite sex civil partnerships on the statute book, there should be a right to convert them to marriage, just as there already is for same sex civil partners – but the government has proposed not to do so. More generally, the need, or the continuing need, for any kind of conversion has been questioned, and whether the option – or options – for doing so should be phased out after a period of time.

There are four possible conversions from civil partnership to marriage and vice versa; ie two for same sex couples and two for opposite sex couples. Currently same sex couples can convert their civil partnership to a same sex marriage, and the government has proposed that opposite sex married couples should be able to convert their marriage to a civil partnership. At first sight these two conversions seem incongruous; insofar one might expect both transitions to be in the same direction, and so matching, eg both civil partnership to marriage, thereby providing a seeming measure of equality. However, there is a good, common, argument for making provision for only these two conversions, based on opportunity of choice, or rather, lack of it. So, most couples in same sex civil partnerships were not able to marry,[13] since same sex marriages were not available, and similarly most couples in opposite sex marriages were not able to form a civil partnership[14] because they, too, were not – and are not yet – available. In contrast, all same sex married couples would have had the opportunity to have a civil partnership instead of marriage, since same sex civil partnerships were possible well before same sex marriages became available. Similarly, all opposite sex civil partners could have married in traditional style, if they had so wished. Hence the availability of the former two conversions can be justified on the couples concerned not having had the opportunity to convert their union, whereas couples wanting to make the latter two conversions did have the opportunity of doing so previously.

Nevertheless, this argument of lack of opportunity should be regarded as only one of several considerations, and does not necessarily mean that only the conversion from opposite sex marriage to opposite sex civil partnership ought to be permitted. Other arguments might be deployed for enactment of one, other, or both of the remaining two conversions,[15] possibly based on grounds of equality or discrimination. Another argument might be that the four conversion options would encourage all couples periodically to review the meaning and legal nature of their relationship – both of which could change over time.[16] Indeed, as mentioned above, some same sex couples regard civil partnerships as a stepping stone to marriage.[17] Nor does the argument of ‘having had the opportunity’ necessarily hold sway with the public if there is strong demand for the other two conversions, although the likely actual numbers would be more decisive. Although a final decision has yet to be taken, it looks unlikely that the remaining two conversions will find their way onto the statute book, but the consultation results, the government’s response, and organised pressure, might prove otherwise.

Nevertheless, despite the reasoned argument by the government, it might usefully be recalled that it only takes one couple – such as Steinfeld and Keidan – with widespread support and a strong rallying argument, citing the banner of equality, successfully to ensure additional rights are created and legally recognised. Indeed, the history of marriage and civil partnership has already been shaped by existing legislation – such as the Equality Act 2010, and the European Convention on Human Rights. In the former, the new ‘Equality Duty’ includes the ‘protected characteristics’[18] of: gender reassignment; belief; sex; and sexual orientation, and also applies to marriage and civil partnership, but only in respect of the need to eliminate discrimination. The European Convention includes the right to marry,[19] and, in Article 14,[20] prohibits discrimination, such as on the ground of sex, and Article 8[21] upholds the right to respect for private and family life.

The government is evidently wary of what might be termed a proliferation of conversion rights, and has had a history of guardedly arguing against extending them, adopting a cautionary approach in the light of developments, most particularly when a new form of civil partnership or marriage has been legislated, creating new possible conversions. One can sympathise with the government’s reluctance when faced with the potential complexity and far-reaching ramifications. In 2012, when consulting[22] about same sex marriage, the government accepted the need for conversions from same sex civil partnerships to marriage but said there was ‘no justification or requirement’ for the reverse conversion. In the most recent consultation[23] in July 2019, with regard to conversions in general, the government’s long term stated view was: ‘We do not want to encourage concepts of ‘trading up’ or swapping one relationship for another. We are also keen to minimise administrative complexity and scope for confusion about the status of relationships or the rights of couples’. Also: ‘this could involve creating conversion rights which may never be used.’

Another argument advanced against allowing all four conversions has been that as well as two of them offering a choice of a legal relationship not previously open to the couple, the other two would allow couples to change their mind and opt for the alternative union to their own. (But, as suggested above, being able to review one’s legal relationship and changing it, if appropriate, could be a healthy exercise.) Being able to ‘change one’s mind’ was not considered a sufficient reason for introducing the appropriate legislation, and, in any event, would undermine, it is claimed, the distinction between civil partnership and marriage. The government did consider bringing to an end the existing conversion right for same sex couples, and introduce no new conversion rights, effectively abolishing new ones altogether, but decided against, as it would deny the opportunity right of opposite sex married couples to convert, as mentioned above. When published, it will be interesting to see the government’s reaction to the results of the consultation – all of whose 6 questions concerned aspects of conversions.

There has arisen another effective kind of conversion (or, rather, a non-conversion); that is, when a married spouse, in a traditional marriage, or a partner in a same sex civil partnership, undergoes a change of gender, in which case existing legislation[24] enables the couple, if they both agree, to continue being married or civil partnered, without divorce or dissolution, and with no break in their union. The latest legislation[25] on opposite sex civil partnerships also seems to make similar provision for gender change, so this facility is available for all four kinds of union.

Less dramatically, there are evidently comparable situations in established opposite sex and same sex marriages and civil partnerships in which one spouse or partner realises their sexual orientation has changed, but for whom it would be inappropriate to consider formally changing their gender. Presumably many such relationships end in dissolution, divorce, or annulment, whilst others continue with mutual acceptance, tolerance, and recognition of the changed situation, albeit all in private. Couples in these situations who wish to continue as partners might wish that their changed union could be recognised legally (but privately), with continuity, as a new one e.g. as a same sex marriage instead of the former opposite sex one. However, there is probably no legal remedy for such a situation, short of a formal change of gender.

Still on the subject of conversion, one aspect of the introduction of civil partnerships – which has been somewhat eclipsed by developments – was the hope that many cohabitants would transform their (informal) union into a civil partnership, especially if the cohabitants had objections to marriage. Until fairly recently, of course, there has only been the possibility of same sex cohabitants becoming civil partners, and it is difficult to estimate the proportion who have made this change. It will be interesting to try to estimate the numbers of newly formed opposite sex civil partnerships which might otherwise have been marriages, or cohabitations. The original hope that cohabitants might choose civil partnerships was that they would enjoy more legal security and therefore greater stability for their union, and better rights and protection on dissolution, if their relationship should fail. A detailed evaluation[26] of this issue concluded that civil partnerships are not a panacea for cohabitants’ disadvantage, largely due to the wide variety of their relationships.

In two earlier consultations,[27][28] summarised in a subsequent policy report[29] of May 2018, three options for the future of (same sex) civil partnerships were proposed: abolishing them and converting them into marriages; stopping new ones, but retaining existing ones; and introducing a new opposite sex civil partnership. The last has since been implemented, and it now seems inconceivable that civil partnerships could be either abolished or no new ones created, such has been the influence and support for them by public opinion.

The current situation, and the history behind it, raises the question as to what conclusions will be drawn, or more importantly, perceptions made, about the relative statuses of civil partnerships and marriages. Arguably same sex marriages and civil partnerships have separately, and in combination, grown in status and acceptability; same sex unions have progressed from suffering from underlying stigma[30] to widespread acceptance, whilst civil partnerships have progressed from innovation to an established alternative to marriage. The combination of the two new elements in the first successful new legal relationship, same sex civil partnerships, suggests there was a ‘marriage value’ (!) in bringing them together. Arguably, too, same sex marriage has enhanced the status of same sex civil partnerships when the options for same sex couples exactly mirrored those for opposite sex couples – and allowing same sex civil partnership ceremonies to be held by religious organisations has also signified their social acceptance. Nevertheless, despite the significant increase in the choice of formalised relationships, the fact that they are formalised will probably still prove unacceptable to some couples, whether cohabitants or those ‘living apart together’.

Clues as to the relative standing of the four different legal relationships can be gleaned from the demographic and social characteristics and background of the parties choosing them. As the three newer legal relationships become further established, and not viewed as new, the relative status of each may depend solely on the distinct form and perception of commitment and partnership roles each offers, or is seen to promise. However, an important element in the argument for having, and retaining, civil partnerships has been that they avoid what many see as the paternalistic aspects of marriage, the couple preferring, it is claimed, to be equal partners, rather than husband and wife with their traditional roles. (Inevitably, though, one wonders whether, had same sex marriage been legislated early and first, there would have been any civil partnerships on the statute book at all.) Overall, there has been extraordinary progress over the last two decades, and much of the advance can be attributed to the adherence to the principles of equality and non-discrimination, which, no doubt, will also play an important part in future reform. Three new legally recognised relationships in the space of less than two decades contrasts with centuries of having only marriage is remarkable, and may signify a new spirit of progressivism.

Acknowledgements

The author particularly wishes to thank Associate Professor Andy Hayward and Professor Chris Barton for helpful information and constructive comments on the text. The author alone is responsible for any error of fact or interpretation, and for the opinions expressed. Thanks are also due to the Department of Social Policy and Intervention, University of Oxford, which provided a range of facilities, and to the Bodleian Library for access to the relevant publications. All statistics have been extracted from the website of the Office for National Statistics, unless otherwise stated.

[1] Civil Partnerships, Marriages and Deaths (Registration etc) Act 2019 – which led to: The Civil Partnership (Opposite-sex Couples) Regulations 2019

[2] British Social Attitudes 36, Nat Cen, The National Centre for Social Research, 2019

[3] British Social Attitudes 36, Technical details p 17 Technical details (natcen.ac.uk) accessed 6.3.2021. The scale is based on a count of the degrees of agreement/disagreement to 5 questions on law, crime, tradition, etc.

[4] Civil Partnerships: Next Steps and Consultation on Conversion www.gov.uk/government/consultations/civil-partnerships-next-steps-and-consultation-on-conversion accessed 4.03.2021

[5] R (Steinfeld and Keidan) v Secretary of State for International Development [2018] UKSC 32, [2018] 2 FLR 906

[6] www.supremecourt.uk/cases/docs/uksc-2017-0060-press-summary.pdf accessed 17.03.2021

[7] see footnote 2

[8] The monthly numbers of conversions for 2017 have been estimated from the known total for 2017, using the 2016 known monthly profile.

[9] Adam Jowett and Elizabeth Peel, ‘A question of equality and choice’: same-sex couples’ attitudes towards civil partnership after the introduction of same-sex marriage, Psychology & Sexuality, 2017, Volume 8, Issue 1-2, pp. 69-80.

[10] (from opposite sex marriages) petitioning wives: 62% of all petitions; petitioning husbands: 38% of all petitions in 2019

[11] Rosemary Auchmuty, The experience of civil partnership dissolution: not ‘just like divorce’, Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 2016, Volume 38, Issue 2, pp. 152-174.

[12] see reference 22

[13] same sex couples could convert their civil partnership – which could be formed from December 2005 – to a same sex marriage only after December 2014

[14] married opposite sex couples will only be able to convert their marriage to a civil partnership after a date specified by prospective legislation

[15] ie conversion from marriage to civil partnership for same sex couples, and conversion from civil partnership to marriage for opposite sex couples

[16] Professor Chris Barton, personal communication

[17] see footnote 27

[18] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/85021/public-sector.pdf accessed 17.03.2021

[19] www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Guide_Art_12_ENG.pdf accessed 15.03.2021

[20] www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Guide_Art_14_Art_1_Protocol_12_ENG.pdf accessed 15.03.2021

[21] www.echr.coe.int/documents/guide_art_8_eng.pdf accessed 15.03.2021

[22] www.gov.uk/government/consultations/equal-marriage-consultation

[23] see footnote 22

[24] Schedule 5 of Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act 2013

[25] Part 5, para 32, of The Civil Partnership (Opposite-sex Couples) Regulations 2019

[26] Andy Hayward, The Steinfeld effect: equal civil partnerships and the construction of the cohabitant, Child and Family Law Quarterly, 2019, 31 (4), pp. 283-302.

[27] www.gov.uk/government/consultations/equal-marriage-consultation

[28] www.gov.uk/government/consultations/consultation-on-the-future-of-civil-partnership-in-england-and-wales

[29] The Future Operation of Civil Partnership: Gathering Further Information, LGBT Policy Team, Government Equalities Office, HMSO, May 2018 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/705768/Future-Operation-Civil-Partnership.pdf accessed 12.03.2021

[30] Wellbeing increased following the legalisation of same sex unions, but is mostly attributed to the reduction of stigma. See: Legalizing Same-Sex Marriage Matters for the Subjective Well-being of Individuals in Same-Sex Unions. Boertien, Diederik, Vignoli, and Daniele. Demography; Silver Spring, Dec 2019, Vol. 56, Issue 6. 2109-2121. DOI:10.1007/s13524-019-00822-1