The absence of the past is a terror, wrote Derek Jarman, in his essential 1993 diary-based book At Your Own Risk, in which he described the trauma of being left out of history, and of not seeing yourself depicted in TV in film, in stories. It’s something those of us in this industry, I imagine, understand is a profound and fundamental human need.

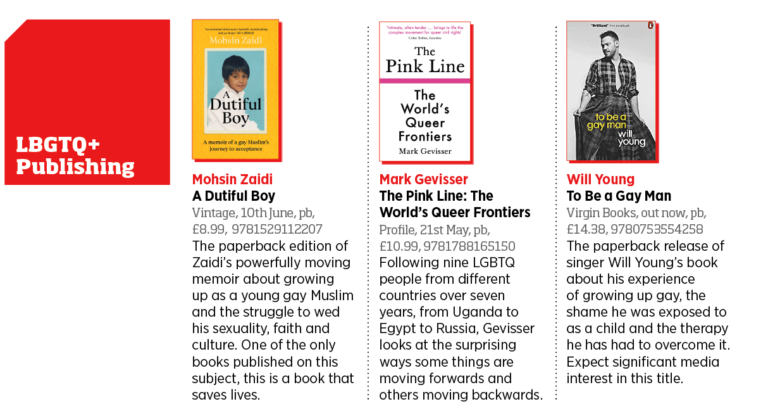

If you are straight, imagine what it’s like to have not had books and films that showed what it’s like to be you: no “Romeo and Juliet”, no “Casablanca”, no “Gone with the Wind”, no Adrian Mole and Pandora, no Bridget Jones and Mr Darcy, no Hermione and Ron, no pretty-much-every-book-ever-written which centres straight relationships in the narrative. I don’t think you could imagine. It’s horrendous. It makes you feel, at a very deep level, that there’s something wrong with you and who you are should be hidden way. It’s so painful writing that list, it makes me want to cry. It’s why in 2017, when the first studio film about a gay teen finding love was released, “Love Simon”, I sat and watched an audience of younger and older gay and lesbian folk weeping. If you are transgender, up until the past five years, it’s most likely you’ll have never seen characters like you in the mainstream. This does matter. As Mohsin Zaidi—author of one of the only books ever published about being gay and Muslim, A Dutiful Boy—explains so sensitively, representation can be a matter of life and death.

When I was a teenager, I went looking in the school library for any books about people like me. I was suicidal, desperate for the support I wasn’t getting in the real world, and I found none. Even if there had been relevant books, I wouldn’t have known because they weren’t talked about. Even E M Forster was so ashamed of his sexuality he made sure that Maurice wasn’t published until 1971, when he was in the ground. Twenty years later, studying Howards End for my A-Levels, a teacher asked why we were reading “that book written by a homosexual”. Even now, there are almost no books or films similar to those, with same-sex relationships at the centre. The ones I did start to read were depressing: everyone died of AIDS or suicide; no lesbian ever survived.

In the mid-Nineties I found Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City series (first published in 1978), about the lives of normal twentysomething people—gay, straight and trans—and I raced through them all. Despite their iconic success, there has still not been another popular gay-themed series since. Is this really because there are no such stories, or writers to tell them?

Clearly not. Of course, lots of LGBT writers tell other stories but this has often been because, as has happened to countless colleagues, we are so used to being told to “de-gay” projects that we often pre-empt and self-censor. In 2012, when I was shopping the proposal for my first book, Straight Jacket, about gay mental health, one publisher complained that it didn’t have enough heterosexual people in it. “That’s the point,” I replied. “It’s about gay people and for gay people.” I wanted to explain that it would be like complaining The Female Eunuch didn’t have enough to interest men in it, but I didn’t.

There are hundreds of writers out there and books that could have made money for publishers. The lesbian author V G Lee springs to mind; one of the funniest and warmest writers in the UK, who has been shockingly under-supported by the industry. There are dozens more. An audience exists, but they need to be marketed to. The recent census will be fascinating. Let’s say 2% of the UK population identifies as LGBT. Would it not be reasonable for even half of one per cent of books published to be about LGBT stories? It makes commercial sense but also strikes to the heart of the publishing industry: what is it for if it cannot tell a diverse range of stories?

Over the past five years the industry has made significant efforts to change this situation. I’m proud to have been published by Penguin Random House, whose WriteNow initiative has actively sought to publish writing from underrepresented communities. Individuals are playing a part too. My second book PRIDE: The Story of the LGBTQ Equality Movement (Welbeck) was championed by Welbeck editor Isabel Wilkinson. Having a gay brother, she is conscious of the urgent need for publishers to platform diverse stories.

Today, as you can see from the round-up of new titles in this week’s Bookseller (30th April), what is notable is the number of YA novels and children’s picture books that are being published. This is important. I mean no disrespect at all, far from it, but over the past 20 years the industry has championed literary gay stories—some brilliant ones—but to my mind, most important is that we see our lives normalised in commercial fiction and non-fiction, especially for young people to see they are not alone. For all the prize-winners (many of which I love and own), what I really needed were teen romances such as Becky Albertalli’s Simon vs the Homosapiens (made into “Love, Simon”). Don’t hate me, it’s true. We were all teenagers once.

Widening representation

It’s heartening to see that on both sides of the Atlantic, work by Black gay voices are being published, such as Paul Mendez’s Rainbow Milk, Bernardine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other, Dean Atta’s Black Flamingo and Brandon Taylor’s Real Life. But it’s still a drop in the ocean. Where do you turn to see yourself if you are a Black or Asian gay man? What if you are a lesbian or bi woman of colour? Publishers such as Jessica Kingsley are doing a stellar job publishing trans voices and it is heartening to see different books from trans authors hitting the mainstream this year, including more work from Juno Roche, Rhyannon Styles, Paris Lees, Monroe Bergdorf and Shon Faye. But it’s taken decades to get here. Will 2021 be a blip?

There also needs to be more ways to ensure the industry recognises what makes a hit in this area too. It’s unlikely many LGBT books will do J K Rowling business, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t breakout hits which should be celebrated. Straight Jacket, the first British title on the LGBT mental health crisis, has been, as far as I can see (sue me if I’m wrong), the most successful non-fiction non-celebrity LGBT book in the past decade, selling steadily for the past five years, provoking constant streams of reader emails and messages. But I’m not sure the industry knows it. I’ve not been asked for new ideas, even though readers constantly enquire about them.

I truly believe that one of the reasons Straight Jacket has resonated is because gay readers are so unused to being spoken to explicitly, directly about their own lives in an authentic voice. When The Bookseller asked publishers to submit details of LGBT-interest forthcoming titles, I noticed the majority were mainstream books which “slipped in” gay or trans characters.

That’s great in many ways. We should be popping up, as in life, but often you can hear the press release desperate not to put off the mainstream by pitching something as “a gay book”; often to the point where they don’t even mention it. I get it. But publishers shouldn’t be scared to commission books for LGBT audiences about specific issues that talk directly to us. If the idea is strong enough, then back it up with marketing and promotional support and big things can happen.

Today, we are moving into a time when centring LGBT characters won’t automatically put off mainstream audiences. I was shocked by the number of both gay and straight people who had no idea how horrendous the AIDS crisis was until “It’s a Sin” was screened. Rejected by multiple channels, it became one of Channel 4’s biggest hits ever. It’s a shame it was not a book that caused this cultural moment, but there are plenty more stories to be told. This is not just a blind spot that the publishing industry has. On TV, I have only ever seen one documentary on homophobic hate crime. The National Theatre is about to produce classic American AIDS play “The Normal Heart”, which will no doubt be brilliant, as was the last classic American AIDS play it produced several years ago, “Angels in America”. As Straight Jacket showed, AIDS is by no means the only huge issue that has impacted the gay community in the past 40 years. There are plenty of British writers who could write the next classic British “gay play”, but they are not commissioned.

A matter of Attitude

It cannot all be laid at the feet of the publishing industry. When I was editing Attitude magazine, I decided to run a piece of short fiction in every issue and asked for writers to submit work. Almost every one was bleak and unhappy. LGBT life does have its challenges, but when the industry tends to never commission commercial upbeat fiction, then perhaps writers think that’s how stories must be told. As Laura Kay, author of The Split, writes, lesbians deserve some happy endings.

Thankfully more of this is coming through. Picture books such as Nen and the Lonely Fisherman would have been impossible to imagine when I was younger. YA fiction such as that of Atta and Simon James Green, celebratory titles such as Jack Guinness anthology The Queer Bible, and novels such as Matt Cain’s gentle and charming The Secret Life of Albert Entwistle, would not have been published 10 years ago. The industry is evolving. It’s important to celebrate. There’s a way to go, but we are moving forward. Let’s keep doing so.

And don’t forget the lesbians. (The Well of Loneliness was a very long time ago).