What does coming of age mean in the middle of a pandemic?

Your first kiss. The first time you partied all night and returned home at 5 am. Your first day at college. Your first heartbreak. The first vacation with friends. The first lease agreement. Your first paycheque. Your first taste of adult life.

If the teen years and the early 20s are when many life experiences debut, something drastically changed last year, with the coming of the COVID-19 pandemic. Much-anticipated milestones never arrived, and a time that ought to have been marked by gay abandon was marred instead by an undeterred stream of stressful situations. Young adults have lost jobs; traded independence for a life of anxiety at home; seen loved ones die as they scrambled for hospital beds; become caregivers to their families sooner than they would have expected.

How can health professionals and the media cut the clutter of false facts around COVID-19?

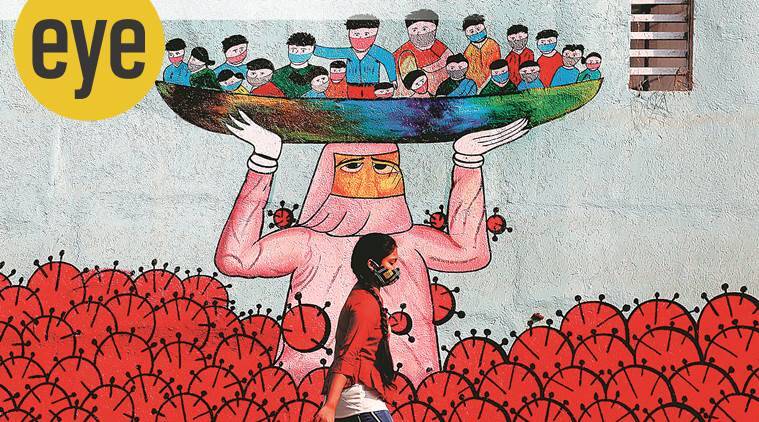

A wall painted with a graffiti of frontline workers in Mumbai, Maharashtra. (Photo: Amit Chakravarty)

A wall painted with a graffiti of frontline workers in Mumbai, Maharashtra. (Photo: Amit Chakravarty)

In the last one year, the amount of time I have spent interacting, engaging and responding to journalists would come next only to the time spent on my public-health work. Nearly 100 years ago, the world had learnt a hard lesson. During the great influenza pandemic of 1918-20, nations fighting World War I had thought that the news of the pandemic would affect the morale of their soldiers and citizens. They censored the press from reporting on the disease spreading widely. Two years later, when the pandemic ended, an estimated 500 million people — a third of the then population — developed the infection and at least 50 (by some estimates, 100) million people died worldwide. Would it have been less severe and the impact on society and the world less if there was no censor on the press? The answer, arguably, is yes.

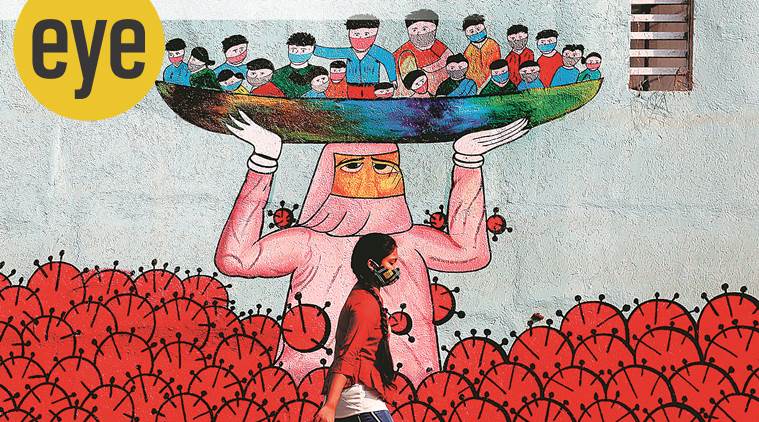

How a son’s photographs of his elderly father’s battle with COVID-19 won him a POY Asia award

Titled “War Comes Home”, the award-winning series, has 18 photographs with accompanying text. (Source: Amit Chakravarty)

Titled “War Comes Home”, the award-winning series, has 18 photographs with accompanying text. (Source: Amit Chakravarty)

In June 2020, photojournalist Amit Chakravarty turned the lens on his 85-year-old father. The novel coronavirus had hit India, and Chakravarty’s father had tested COVID-19 positive. “I was arranging things in the hospital, where my father was admitted, when the nurses told me to wear a double mask and a PPE kit. I had to talk to them from a distance of 10 feet. The idea of communicating from such a distance is what caused me to document my father’s illness,” says Mumbai-based Chakravarty, who has been working with The Indian Express for eight years. Previously, he has worked with publications like TimeOut.

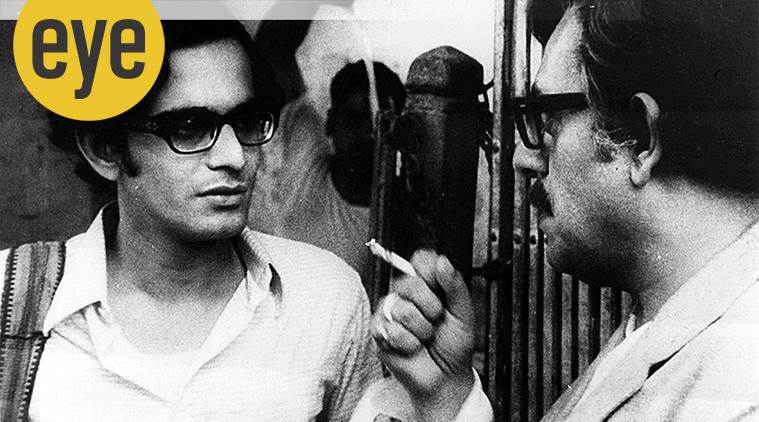

On his birth centenary, a tribute to Satyajit Ray through images captured by his friend and colleague of over two decades, the late photographer Nemai Ghosh

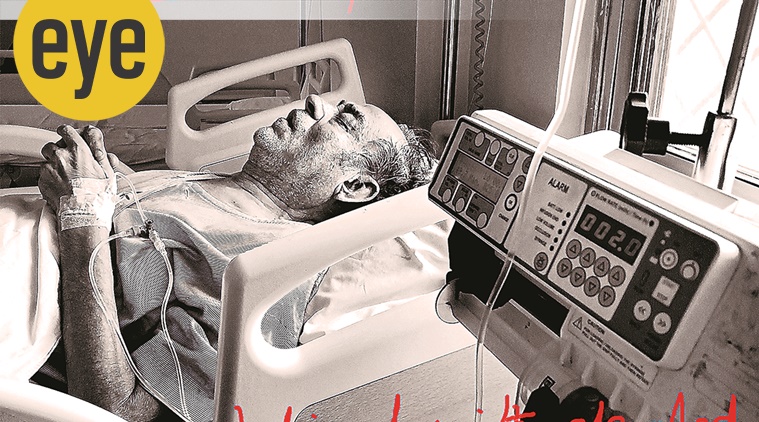

(Ghare Baire, 1984). Ray composes music on a synthesiser at home, 1982. “I am afraid Calcutta is now short of musicians,” he said in the mid-1980s, “and you have to fall back on the synthesiser much of the time. For instance, there’s no oboeist in Calcutta, no cor anglais, horn or brass players. I’m not very happy using the synthesiser, anywhere in my films, except for the oboe tone: that’s one tone the synthesiser can produce very faithfully.” Photograph by Nemai Ghosh, courtesy Delhi Art gallery (DAG)

(Ghare Baire, 1984). Ray composes music on a synthesiser at home, 1982. “I am afraid Calcutta is now short of musicians,” he said in the mid-1980s, “and you have to fall back on the synthesiser much of the time. For instance, there’s no oboeist in Calcutta, no cor anglais, horn or brass players. I’m not very happy using the synthesiser, anywhere in my films, except for the oboe tone: that’s one tone the synthesiser can produce very faithfully.” Photograph by Nemai Ghosh, courtesy Delhi Art gallery (DAG)

“In a sense, the possibilities of fusing Indian and Western music began to interest me from Charulata (1964) on. I began to realise that, at some point, music is one … Especially for my contemporary films … I knew that raga music alone just would not do: because the average, educated middle-class Bengali may not be a sahib, but his consciousness is cosmopolitan, it is influenced by Western modes and trends. To reflect that musically you have to blend — do all kinds of experiments. Mix the sitar with the alto and the trumpet and so on.”

—Satyajit Ray

How Satyajit Ray’s films throw up prescient images of viruses afflicting societies

Interpreter of Maladies: Still from the film Jana Aranya (1976) (Photo: Express Archive)

Interpreter of Maladies: Still from the film Jana Aranya (1976) (Photo: Express Archive)

In Mahanagar (The Big City, 1963), when Arati’s (Madhabi Mukherjee) chatty boss Mr Mukherjee (Haradhan Banerjee) drops her home one evening, while navigating the congested lanes of Calcutta’s Kalighat area, he speaks — in an attempt to impress her, perhaps — of how he feels for the pedestrians and tries to give them a lift in his car. It upsets his wife, a stickler for hygiene, who requires “three bottles of Dettol per month”, he says. She tells him, “How do you know they aren’t carrying infectious germs? Disinfect the car or I won’t ride in it”. In one seamless sequence, director Satyajit Ray masterfully establishes class divide, “othering”, and prejudice of how the haves consider those off the streets as “carrier of germs” and obsess over sanitising themselves. The scene has uncanny resemblance to our times when the coronavirus has made people socially distant, every human a “carrier of germs”, and every class of people relying on sanitising liquid to keep the virus at bay!

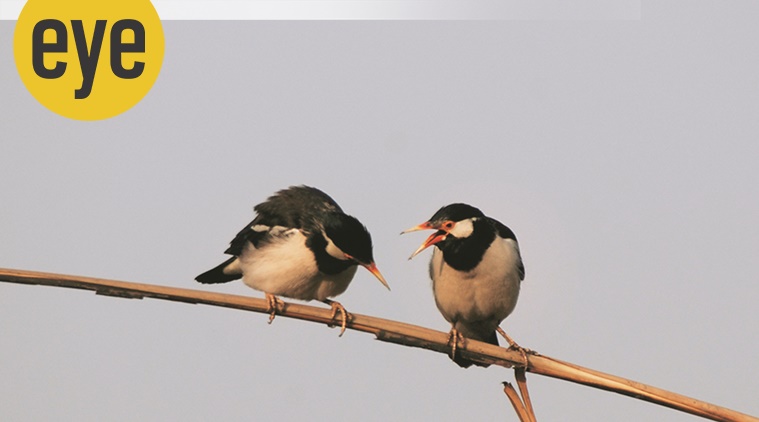

How TV talk show and news anchors can benefit from mynahs

Mynah Talk Show: The birdies can teach humans how to hold civilised discussions (Ranjit Lal)

Mynah Talk Show: The birdies can teach humans how to hold civilised discussions (Ranjit Lal)

A major characteristic that sets us apart from the rest of the animal kingdom is language. We’re so proud of this that we’ve even begun teaching the brighter stars of the animal kingdom English, if not American Sign Language (ALS). There was Alex, the famous African grey parrot, the subject of a 37-year-old experiment, who was taught to “converse” in English (there have been several since he died), and the gorilla Koko, who was fluent in ASL and had an English vocabulary of over 2,000 words. Her last message to us was “man stupid” and “save Earth”. A bit far-fetched, but who knows. After all gorillas don’t go about hacking and burning rainforests and waging war, or spreading bat viruses, do they? Researchers have even tried to figure out whether animals have their own language.

Why the President’s Bodyguard horses are the best-groomed in the country

The agility, faithfulness and valour of the horses have added to the regiment’s colourful history, that continues to inspire generations every time they escort the President of India for ceremonial functions.

The agility, faithfulness and valour of the horses have added to the regiment’s colourful history, that continues to inspire generations every time they escort the President of India for ceremonial functions.

History of humankind, it is said, cannot be written without a reference to our special bond with the horse. That is also true for the President’s Bodyguard (PBG), which prides itself as the senior most regiment of the Indian Army. It has a legacy of nearly 250 years, but its story is incomplete without a nod to this magnificent animal, and the role it has played over the years in the battlefield, in the sporting arena and even in the regiment’s stables.