It wasn’t me who drove the plan forward to move to Manchester. It was my boyfriend. He wanted to live in a place where we could live more openly. We’d met in our hometown, a small Yorkshire town called Doncaster. We wanted to live without judgment and Manchester was the closest place to do it. We didn’t do it exactly together, but we moved at roughly the same time. I packed my bags for liberation just shy of my eighteenth birthday.

Oh my gosh, Manchester. It was absolutely eye-opening. I’d been going there for years anyway, because we have family close by, without ever discovering the city center. I only really knew the suburbs. South Manchester, and Chorlton in particular, was full of students and ex- students, which automatically meant that it was the most liberal place I’d ever lived in. We’d go out to the Gay Village around Canal Street and socialize among people who were not only openly gay but openly comfortable with their gayness. It was something I’d just never seen in my hometown, where being gay was still the subject of ridicule, gossip, and scorn. So, the majority of my experiences as a gay man I learned in Manchester.

For me, these were the places where I learned not to hide any of my femininity, at all. On the most basic level, it was about not needing to hide those things that were natural to me that I had felt the need to keep covert before. If I had a limp wrist, I had a limp wrist. A high voice? That’s fine, too. If I wanted to talk about Britney Spears, I could. It made me feel like I was safe to be the person I wanted to be and to no longer have to suppress the things inside of me that had previously been locked away. Because nobody, quite frankly, gave a fuck. I love Manchester for that.

The TV climate of the time was funny. Weird, not haha. It was the start of the millennium. Change felt imminent but not yet fully realized.

The first gay people I saw on TV were the cast of Will & Grace. I’d known there were gay characters in the seventies and eighties, but not many, and I didn’t watch those shows anyway. But I would watch and be fascinated by the world of Will & Grace. What I found so fascinating was how clear it was to me that these people were not a version of me. They were either hyper-stereotyped versions of gayness, like the Jack character, or someone who was obviously played by a straight guy, like Will. Will would try to camp it up slightly but never quite enough to make a gay audience feel absolutely seen. These two extremes seemed to be on TV to make straight people feel comfortable about the idea of watching gay characters. And that was great, truly. They represented the possibilities of what a gay person might look like to that audience. But to a gay man watching the show it wasn’t entirely clear that they took in the multitudes of gayness. What about the men who didn’t have to try to camp it up?

Like I say, that was OK. Will & Grace was a scripted show with a clear intention. But then Queer Eye happened, and my mind was blown. It was the first show I’d watched gripped, where it was very clear that these people were gay, or queer—however they wanted to identify—24/7, around the clock, off camera as well as on. It was an important distinction for me. They talked in their own voices and said what they wanted to say, as identifiably real-life gay men. This was a first for me. The first time I felt like, what? We’re allowed to be ourselves on TV? That is insane.

Even though Queer Eye was—and still is—a makeover show, the presenters said what they wanted to say in their honest voices. They were true queer men. They reimagined what the word “queer” meant to me. Back in the day, when I was growing up, the word was only associated with shame. There was a long time when hearing the word at school sent a shudder through me. I wouldn’t hear it directed at myself because I was stupid enough or clever enough to pretend not to be queer. I can be angry for allowing myself to live that pretense at the time, but I forgive myself now because there was no option to behave any differently and remain unscathed. This is one of the reasons why I get it when people act from a place of shame and deny their true selves. Why did I have to convince these idiots that I was straight? Because the world is not set up for queer people. It’s built around a “straight” model, whatever that is. So sometimes living an imaginary or modified life is a question of survival in small towns. It certainly was then.

For me, being gay wasn’t a problem, but for other kids it was. “He’s a queer,” “he’s a poof.” That was a language I grew up with as routine. I heard it a lot, even if it wasn’t directed at me, and the whole idea of being gay was equated, in those little moments of casual cruelty, with feeling ashamed of something at your core. It wasn’t until I was in my thirties that I understood the word to mean something positive. Queer Eye must have triggered that. We’re not something straight; we are something different from that and that’s OK, that’s beautiful. We are queer, and for me, that started to mean different or unique. The word started to shed some of its negativity. Queer Eye had a lot to do with that. Now it fills me with pride to think that I am one of those Queer Eye boys. I’m not dancing to the same beat as everybody else, and that is fine. That makes me feel strong. It’s a source of great power, not having to conform to what people expect of you. I hate the word “normal” anyway, a word that now sounds like more of an insult than queer used to. Who, in all honesty, wants to be that bore?

I’ll be honest. When I got the Queer Eye job I only watched half an episode of the first American series, because I didn’t want to be inspired by the US original Fab Five and become a cheap knock-off of Carson. I didn’t want to subconsciously channel him in any way. But the British version had changed something in me back then in Chorlton when it ended up popping on my TV one night. It chimed with my new life.

I can remember it coming on the TV as if it was yesterday. I was sitting with my boyfriend and was immediately struck by how fab these guys really were, in the best and worst possible way for the early 2000s. It was so weird that they referenced their life outside of the show, something actors on scripted drama or comedy could never do. They were naturally funny and charismatic and, most importantly, naturally queer. That felt so different to a script. It was so nice to imagine what their life might look like outside of the show—these men who didn’t take off the costume of a gay man and disappear back to the arms of their girlfriends.

Its appeal wasn’t that it was a makeover show and that I couldn’t wait to see the next episode. That it was nice, it was entertaining. What was truly revolutionary for me was that I was able to talk about it with my boyfriend and my friends, knowing that they were going back to their boyfriends or partners or however they articulated their queerness in a real way. That impacted me in the most positive way. It was something I simply hadn’t seen before. Somebody on TV allowed to talk about what their life was like outside the show was something I had never experienced before. It brought a 360-degree gay experience right into the home. Not something that someone turned off and on for the camera. These men were working together—who knows what their relationships were like off screen, but on screen they were helping somebody improve their lives by bringing their own, rounded, fully gay experience to bear on the most important aspects of their lives. Gay men were useful, at last! Gay men weren’t the butt of the joke anymore or wheeled on as a joke for comedic relief. Their opinions and expertise were respected, and their “gayness,” that point of difference, was central. That they were introducing their experiences to other people in an affirmative, positive way made the show somehow holistic. “Queer” suddenly felt like the opposite of shame.

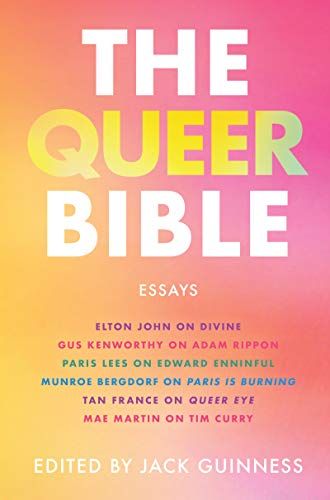

Adapted from THE QUEER BIBLE by Jack Guinness, published by Dey Street Books. Copyright © 2021 by Tan France. Reprinted courtesy of HarperCollinsPublishers

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io