In the fall of 1970, as the Vietnam War raged, five guys from the New York City Gay Liberation Front took a meandering road trip through the South in a maroon-and-white Volkswagen Bus. Their mission? To inspire gay people to attend the second Black Panther–organized Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention in Washington, D.C., where they would join other liberationists from all around the country in writing a new American constitution.

Together, they spent six weeks on the road—Diana Ross and Mick Jagger on the radio, freedom and fear in the air. Joel was the radical; Richard, the lover; Giles, the organizer; Jimmy, the enfant terrible; and Doug, the cipher.

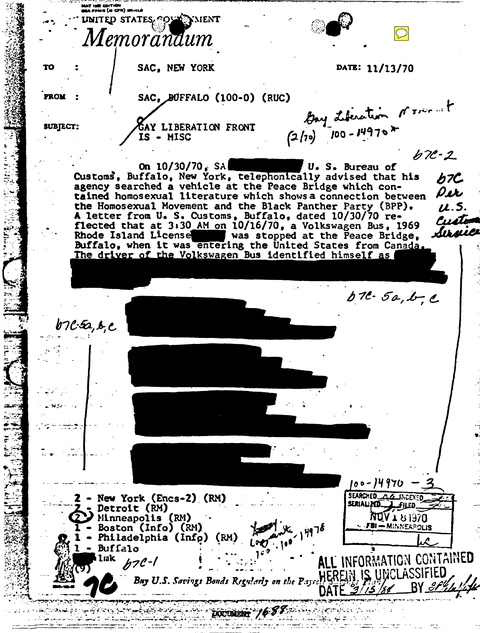

Before they even got underway, the government was watching them, worried about “a connection between the homosexual movement and the Black Panther Party,” a federal document shows.

The FBI was sowing discord among radicals, and it was easy for mistrust to take root. Once, these guys were lovers and comrades; now, some of them can’t even be in a Zoom with one another. But briefly, in the autumn of 1970, they saw a chance for a revolutionary future, and they struck out for it together.

Doug died of AIDS-related lymphoma in ’93, and I was never able to agree to the terms Jimmy set for an on-record interview, but Joel, Richard, and Giles were eager to share their memories.

Fifty years later, their stories are a patchwork quilt of collectives, communes, free love, coming out, getting arrested, consciousness-raising rap sessions, gun shooting, acid dropping, and trying to be macrobiotic at McDonald’s. Their versions vary widely, and reality lives somewhere unlocatable in the blurry overlap.

As a historian, I’m used to making the pieces fit, but it’s always something of a guess. Sometimes, the fragmentation is the story. Sometimes, the pieces are all we have. We’re told hindsight is twenty-twenty, but frankly, that’s bullshit. We’re fallible now, we were fallible then, and we’ll be fallible again tomorrow.

But that shouldn’t stop us from climbing mountains.

This content is imported from Third party. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Joel: Okay, for my part, this is my story. There were five of us living in a collective together on the Lower East Side of New York, on 7th Street and Avenue C. Richard, Jimmy, myself, Giles—who else? Doug. Doug and I were the only two Black men in that collective. We were full-fledged Gay Liberation and Black Liberation and everything else people.

Giles: Richard was bar none the best-looking man in Gay Liberation. And Joel was the greatest dance partner I ever had. We would get up there in front of everybody and do the dirty bump as if it was propaganda.

Richard: I was living with Doug and Joel in a ménage à trois, and that was really wonderful.

We couldn’t get regular jobs—everybody asked what our draft status was. [Instead], I had this International Rubdown service. We advertised in the Village Voice, $20 a rub. Because it was “International,” we had different names. I was Hans, the German, and Thor, the Swede.

I was also working with this underground printing press, printing stuff for the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, etc. And Jimmy owned a van, like a VW caravan, and he started talking about this trip. I don’t remember anything about bringing people to the Panther convention. But Jimmy recruited us. We were on for the ride and for the adventure.

Giles: Jimmy had been involved with the Panthers. And I was knowledgeable about the underground press, so I’d call ahead to these newspapers, and say, “We’re coming on a tour organizing for the Black Panthers’ Revolutionary Constitutional Convention. Do you know any gay people?”

Joel: We went from Fayetteville, [North Carolina], to New Orleans, to Dallas, to Boulder, Colorado, to Iona, Minnesota. We would contact Gay Liberation in each area, and they’d invite us to speak about what we were doing.

Living a revolutionary life, to me, is always questioning, always questioning myself, and questioning other people about what it is they know. It was a way of living. It was just … who we were. There was no thrill in wanting to have a revolution. Who wants to go through that? Unless you have to.

But I wasn’t scared or anything like that. I never felt scared—well, no, the only time I was scared was in Dallas, when we got arrested.

Life on the Road

Richard: Who drove? I think we alternated. Doug and Joel and I, we were sharing clothes and living that way, very much sharing everything, cooking together, figuring out how to be macrobiotic. We’d stop at fast-food places because sometimes, that was the only food that we could afford and the only thing along the highway in the middle of America.

Giles: We might’ve had one pair of jeans, maybe one pair of cutoffs, and a couple of shirts each. Maybe a winter coat. None of us had a lot of clothing. We were proselytizing, so when we’d meet people, we’d sit on the floor in a circle, or in chairs, and spread the word about Gay Liberation.

Joel: The conversations were basically around what it was we were feeling as gay men and how we could move people to come to this convention so that we could organize ourselves.

First Stop: North Carolina

Giles: Greenville, North Carolina, was one of the first places we stopped, because it was a center of leftist organizing in the textile mills. And there was a lot of Klan activity too. We’d made a kind of ideological decision: We have to come out to our parents. Doug’s family were country people, outside Greenville, and he told his mother that he was gay, and she was obviously stricken.

Richard: What happened with Doug and his family, as well as with me and my family later, was about beautiful Southern and Midwestern hospitality. Doug and I had a dog, and we left the dog with Doug’s family, then continued down to Georgia.

Georgia

[No one remembers Georgia.]

New Orleans

Joel: We stayed at different people’s places. I mean, we didn’t spend very much money, because we didn’t have very much money! They were mostly young, white, gay men that were involved in Gay Liberation. Occasionally, we would see Black men. But there was a clear separation of Black and white communities, which is still a problem.

Giles: We made contact with this gay man who had a shelter in the French Quarter for gay adolescents who had been thrown out by their families. It was a little bit sketchy, and maybe exploitative. I remember being charmed by it, but also [thinking] that this place was certainly not glamorous at all. We did all the classic things, having beignets and coffee. Then, from New Orleans, we drove possibly to … Dallas?

Texas

Joel: As soon as we entered Dallas, honey, they pulled us over. Well, I won’t get into the details of why. I’ll let other people talk about that. But it had nothing to do with anything other than that we were two Black men in that car with those white boys. We had sworn before we left New York that there were no drugs in the car ever. That was a rule that we all decided that we were going to follow.

Richard: Just around the freeway into Dallas, some big construction truck tried to force us off the highway. Then we were busted, because we were Black and white people together, looking like hippies, in a VW van. Pot was the only thing we had, and fortunately, I stashed it under the seat and the cops didn’t find it.

Giles: We didn’t have any weed on the trip. We weren’t smoking weed. The two rookie cops immediately searched Jimmy and found four tabs of acid in his jacket.

Richard: We were all held in a jail compound with lots of other people and had to hang through it for three nights. There must have been like maybe 20 other people in the cell. You were asking about a lesson from all this? Lesson number one was I do not want to go to jail.

Joel: I thought I was in jail for life because first of all, it was in the South. I don’t like going to the South, because I had done that as a child with my parents and it was horrible. Horrible experience to have to deal with. For a young Black child to have to witness his parents go through the shit that they had to go through just to get to Mississippi. … I never thought we’d get out of that jail.

Giles: Jimmy was prancing around in the holding cell in leather pants with snakeskin boots on, flipping his long blond curls. And Joel, who had been in jail, and I, who had been in jail, said, “Jim, come over here, sit the fuck down, and stop attracting potentially violent attention!”

Richard: Jimmy’s lawyer got us out in three days.

Joel: We were out before we knew it. I was surprised. I think the Gay Liberation Front got us out.

Giles: Because the two rookie cops did not get a warrant to search us, that’s how we got off. I called my parents in Shreveport, [Louisiana], after. They were terrified that I’d become a mad bomber. So I started the call by announcing that I was gay, and on a tour to recruit gay people for Gay Lib. My father burst into hysterical laughter—because what he had suspected was finally confirmed—but most of all, they were simply deeply relieved that I wasn’t a bomber.

My 21-year-old lesbian sister was listening to the call. She was there with her first girlfriend, whom she had met through my mother. It was her first direct knowledge that I was gay, and that there was such a thing as Gay Liberation.

They proceeded to have a wildly joyous and drunken party in celebration.

Joel: I was furious with Jimmy. Everybody was upset, but we didn’t clobber him over the head with it. We just went on with our mission.

Red Rocks Commune, Huerfano Valley, Colorado

Giles: My friends had gotten this crazy idea of having a commune in the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, near Pueblo. They built these geodesic domes. It was very much in the rocky, semiarid foothills of the mountains, way the fuck out in the middle of nowhere. There was snow on the ground, and they were stoned utopians living the hippie dream.

I had harbored this Weatherman, who was involved with the Days of Rage out in Chicago. I fell very deeply in love with him, and he was there at the commune. The FBI was looking for them like mad. They put us up for a day or two.

Iona, Minnesota

Joel: Then we stopped at Richard’s parents’ house. I met his mother and father. They were so sweet and so kind.

Richard: My parents were very welcoming of us, I felt the same there as at Doug’s in North Carolina.

Joel: Richard’s father took us out and taught us how to shoot a shotgun. I had never shot a gun before in my life, never even handled one. It was very surreal and kind of exciting. I knew at that point that that would not be anything that I would pick up again unless I had to.

But there’s a feeling in the air all the time for Black men who are gay—the possibility of us being offed just because we’re walking down the street.

Richard: Some of us had been in meetings in NYC about organizing a gay revolution party, thinking a Panther-like strategy of becoming armed might be essential. So we grabbed a couple rifles, took them out to a pasture near town, and shot cans and fence posts.

And I realized, this is not going to happen. These guys are never going to become militant revolutionaries. And I’m not going to either.

Giles: We all dropped acid—where that came from after we had been busted in Dallas, I don’t know—and went out to practice target shooting with bottles on a fence, while we were tripping! Nuts.

Still high, we came in to dinner. Richard’s parents had cooked some classic luscious steaks for supper. All of us sat there virtually mute and stoned out of our minds. I remember looking at my steak and being unable to eat it, as it pulsated with rainbow-tinged vibrations off the flowing rare juices.

Louisville, Kentucky

Giles: The last leg that I recall was Louisville, Kentucky. I contacted two friends of mine, Cecil and John, who were my first gay friends as an adult. In the previous four years, Cecil had grown, and he was the most godlike man I have ever seen in my life. He wanted to come to the convention. There was no reason in the world why he shouldn’t have come along on that trip, but he didn’t. The nasty part of me lays it on Jimmy and Richard, in particular, who were the ones driving. They didn’t want to take on any of the sexual tension. They said no.

Richard: I think we did go to Louisville. I remember Kentucky, but Cecil … I don’t remember any names from that trip.

The Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention, Washington, D.C.

Joel: When we got to the convention, everybody was there. I was shocked because I thought it was mainly going to be gay people that we were conferencing with, but we ended up conferencing with everybody. It was absolutely fantastic.

Richard: We didn’t go to the convention.

Giles: We went to the convention, but I have no memory of it whatsoever.

The Panthers envisioned a new America, governed by a radical constitution, which could only be written by a group as diverse as the country itself—a revision to the version made by 55 white male landowners, 200 years before. Inspired by this idea, 5,000 revolutionaries joined them in Washington. Government interference, internal strife among the Panthers, and external divisions between the invited groups prevented the constitution from ever being finished. But as Huey P. Newton, a Panther cofounder, once wrote, “[Revolution] is not a particular action, nor is it a conclusion. It is a process.”

The dreams of the radical Seventies never failed; they are simply still unfinished.

Afterward

Joel: So we go back to New York. Richard decides to move to Hawaii. I go back to Chicago. Everybody dissipates and disbands, but our lives continue to be revolutionary. Everything I do is Black, and everything I do is gay, because I’m Black and I’m gay. I live a revolutionary life by even existing.

Richard: It was a great trip. I’m really grateful for it. It emboldened me to connect with people who live from the heart and make them my mission. Whether you’re straight, or not, or mostly, or whatever, having this ability to love and appreciate our fellow humans is what it’s all about.

Giles: Nobody ever wrote this up. Nobody ever talked about this. It’s not a widely known event. Everywhere, all over the country, in San Francisco, in every fucking town, every city, there was some version of this happening that got lost and didn’t get told or is only now being recovered.

Coda

|

Apr 21, 2021 |

|||

|

||||

Hi Hugh,

I got an email from Micky saying you were looking for information about a group of gay men that visited the Louisville Gay Liberation Front group back in 1970.

I do remember their visit, though not a lot else.

I remember that one of the men was Giles ******, because I had graduated from high school with his younger brother. I think one of the other men in the group was Jim *****.

My recollection is that they had gone to a Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia held by the Black Panther Party, and there was going to be a second convention in Washington, DC, on Thanksgiving Day weekend, and they wanted to see if anyone from Louisville Gay Liberation Front would attend. And five of us did, driving up from Louisville to Washington.

Hope this helps, and let me know if you have any more questions.

At this point in time, I just want to be sure the history is there for all of us.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io