Over the past half-century, understanding of health and health care disparities in the United States — including underlying social, clinical, and system-level contributors — has increased. Yet disparities persist. Eliminating health disparities will require a movement away from disparities as the focus of research and toward a research agenda centered on achieving racial equity by dismantling structural racism.

In the 1970s, the same decade that the Institute of Medicine (IOM), now the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), was founded, researchers began to see a clear pattern of disparities in the health of Black people and other minority groups as compared with White people in the United States. More Black people than White people died from cancer, for example, even as more effective treatments became available, and American Indians had substantially higher rates of diabetes than White people.

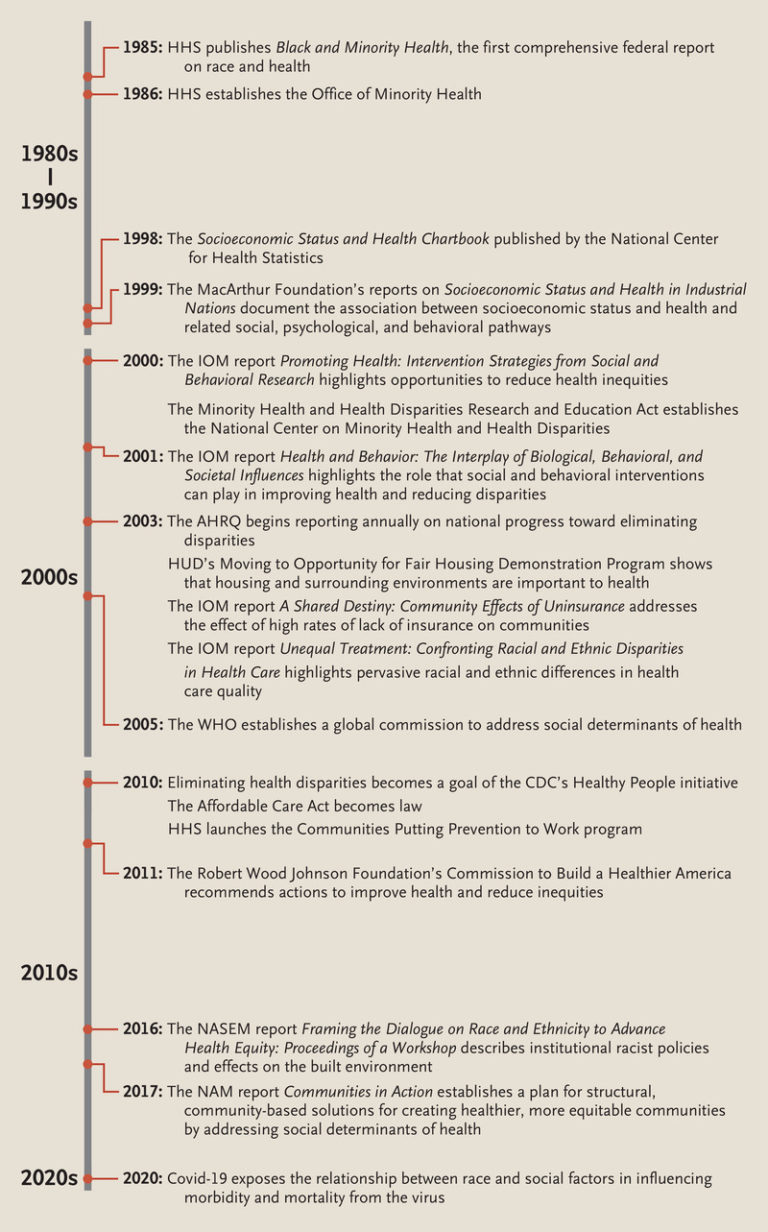

Publications and Events Related to Heath Disparities and Health Equity in the United States.

Publications and Events Related to Heath Disparities and Health Equity in the United States.

AHRQ denotes Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HHS Health and Human Services, HUD Housing and Urban Development, IOM Institute of Medicine, NASEM National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and WHO World Health Organization.

In light of the clear need to understand the drivers of such disparities and to design effective interventions, in 1985, Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Margaret Heckler released Black and Minority Health, the first U.S. government report to focus exclusively on the health of racial and ethnic minorities (see timeline). The report, which documented a higher burden of disease and lower life expectancy among Black and other minority populations than among White populations, called for enhanced data collection to design effective interventions. This report launched a new era of productive research and led to the 1986 formation of the Office of Minority Health, with the goal of improving the health of racial and ethnic minority populations by implementing new health policies and programs.

Although data collection on health disparities between Black and White populations began to improve after the Heckler report, data related to other marginalized populations remained scarce. Efforts were soon launched to collect data on health status and health care outcomes based on race, ethnic group, language, and other important characteristics. Beginning in 2003, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality reported annually on progress toward eliminating disparities. Improvements by private organizations and state agencies in collecting and analyzing data helped refine the reporting and understanding of factors associated with disparities. But disparities were not eliminated, and gaps in data emerged (and persist) regarding disparities faced by Asian and Latinx people; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer people; and people with disabilities.

The Socioeconomic Status and Health Chartbook, published by the National Center for Health Statistics in 1998, added an important dimension to the understanding of the basis of health disparities. The report explored for the first time the associations between health and socioeconomic status and between race and health for a broad range of outcomes. Like the Heckler report, the Chartbook led to a wellspring of new research. In 2000, the Minority Health and Health Disparities Research and Education Act established the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, along with a dedicated research budget to explore strategies for advancing health equity.

Researchers turned next to drivers of health disparities within the health care system — chief among them unequal access. The IOM issued a six-volume series documenting the effects of lack of insurance on access to various types of care, from preventive services to care for chronic or potentially fatal illnesses, such as cancer and renal failure. The reports tied disproportionately low rates of health insurance among minority populations to low availability of community-wide health care services — and, in turn, to health disparities. These reports illuminated the way in which a community’s health status could be linked to its residents’ insurance status.

Congress also tasked the IOM with studying racial and ethnic disparities in quality of care, evaluating potential sources of these disparities, and recommending interventions. The resulting 2003 report, Unequal Treatment, explored the continuum of services from hospital-based care to rehabilitation and long-term, home-based, and outpatient care. One finding captured headlines: “Racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare exist and, because they are associated with worse outcomes in many cases, are unacceptable.” The report documented disparities in most clinical interventions — from basic interventions, such as pain management, to complex ones, such as cardiac revascularization. Although Unequal Treatment acknowledged the influence of socioeconomic factors on health outcomes, it did not explore specific linkages between socioeconomic status and health care or recommend solutions that integrated social and health care–related factors.

Another IOM report published around the same time, Promoting Health, did highlight the role that integrated social and behavioral interventions could play in improving health and reducing disparities. This idea began to shift researchers’ and policymakers’ focus to the community as the natural heart of strategies for reducing health disparities. In 2010, for example, HHS launched the Communities Putting Prevention to Work program, which partnered with 50 communities to reduce rates of obesity and tobacco use.

Twenty-five years after the Heckler report, researchers had made substantial progress in collecting and stratifying data on the basis of demographic dimensions, in understanding the relationship of socioeconomic status and inequitable health care access and quality with health outcomes, and in recognizing the necessity of structural change to achieve health equity. This potential has yet to be realized, however.

The research that emerged after the Heckler report made it clear that health disparities cannot be reduced by targeting individual clinical conditions. Instead, the field has turned toward the exploration of structural factors, such as the role that structural racism plays in segregating society and limiting opportunities for health and well-being, as essential to advancing health equity.

An important investigation demonstrating the effects of neighborhood on health was a randomized study led by the Department of Housing and Urban Development that gave families living in public housing vouchers to move to market-rate housing or remain in public housing. A decade after the intervention, people living in market-rate housing in high-income areas had lower rates of obesity and diabetes and higher levels of physical activity than those still living in public housing, and they reported improved mental health and well-being.1 Despite the study’s limitations, it demonstrated that housing and the surrounding environment matter.

More recently, economist Raj Chetty and colleagues showed that people living in places with more upward mobility have longer life expectancies than people living in places with less upward mobility.2 The benefit is greatest for high-income people, but the trend is consistent for all income levels. The characteristics of places with more upward mobility — social cohesiveness, educational opportunity, a strong middle class, and little racial segregation — mirror the social factors associated with greater health equity. In this vein, the 2017 NAM report Communities in Action established a plan for structural, community-based solutions for creating healthier, more equitable communities by addressing social determinants of health. The report did not address racism directly, but Chetty has also demonstrated that prospects for upward mobility are substantially constrained by race — a clear effect of racism.

Another structural factor that affects health disparities is insurance coverage. Jie Chen and colleagues were among the first scholars to publish research showing the positive effect of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) on disparities.3 According to their findings, after the law’s implementation, the likelihood of being uninsured decreased in all groups — and it decreased substantially in Black and Latinx populations, which previously had disproportionately high rates of being uninsured.3 The likelihood of delaying necessary care also dropped in all groups (and especially among people of color), as did the likelihood of forgoing care. The ACA, therefore, had positive effects on an important underlying contributor to health disparities — lack of access to care.

In 2020, two events increased public awareness of structural barriers to good health, particularly for racial and ethnic minorities, and could engender new interventions and policies. One of these events, the murder of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, by police, sparked a massive cultural confrontation of structural racism and the systemic factors that cause Black people and other people of color to be sicker and die earlier than White people in the United States. The other event, the Covid-19 pandemic, sickened, hospitalized, and killed people of color at higher rates than White people because of many factors, including an increased risk of exposure, unequal access to testing and high-quality care, higher rates of medical conditions associated with poor outcomes, and less access to vaccination. These events could increase political will to address the structural racism that drives inequitable health outcomes — thereby creating an unprecedented opportunity for researchers, advocates, and policymakers.

Amid increased understanding of the effects of structural racism on health, research by one of us and by Dorothy Roberts,4,5 among other scholars, has led to a view of race and ethnic group as social constructs, not medical risk factors. This research suggests that addressing the effects of racism, ethnocentrism, homophobia, unequal treatment based on immigration status, and sexism on health will be beneficial for overall health status and outcomes. Going forward, improving the effectiveness of interventions aimed at mitigating individual and institutional bias, whether implicit or explicit, will be essential to advancing health equity.

Future progress will rely on putting all the pieces together. The past five decades have seen great strides in terms of understanding the nature and scope of health disparities, their socioeconomic and health care–related drivers, and the importance of dismantling structural racism as a path to achieving health equity. Researchers and policymakers increasingly understand that health solutions must target manifestations of structural racism — such as barriers to economic mobility, access to high-quality education and health care, and access to high-paying jobs — and the policies that allow racial inequities to persist. Health systems researchers should continue moving away from focusing on health disparities and toward looking at root causes: systems of structural racism. Only by addressing underlying structures will we get closer to a day when a person’s health prospects are no longer predicted by the social construct of race.