Yasmany Sánchez Pérez had an awakening when he read “Before Night Falls”, the autobiography of Reynaldo Arenas, a gay Cuban writer condemned by the country’s dictatorship because of his sexual orientation and political opposition. His way of seeing the reality that surrounded him completely changed and he saw his life portrayed in the pages of that book the regime banned. Sánchez, like Arenas, has been persecuted and harassed by Castroism’s homophobic minions.

Although they are separated by 50 years of history, this chronic intolerance on the part of the Cuban regime against those who raise their voices in defense of the rights denied to them as human beings prevails.

Sánchez, 28, made himself heard on May 11, 2019, when he joined a Havana march that independent LGBTQ activists organized in response to the National Center for Sexual Education’s decision to cancel their annual march in the Cuban capital that commemorates the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia.

CENESEX, which Mariela Castro, daughter of former President Raúl Castro, directs, spearheads government-sanctioned LGBTQ activism in Cuba. The decision to cancel their IDAHOBiT march in Havana prompted hundreds of Cubans to participate in the independent event, which the regime interpreted as an act of political dissent.

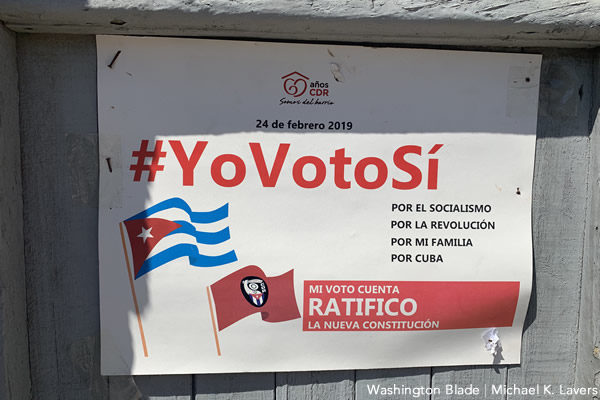

The march, organized through social media, took place less than three months after Cubans ratified their country’s new constitution.

A previous draft contained Article 68, which would have opened the door to marriage for same-sex couples in Cuba, but the National Assembly removed it in response to pressure that various religious denominations put on the government and reported opposition from the Cuban people. The National Assembly instead said a referendum on reforms to the country’s Family Code will take place within two years.

“That cancellation was the last straw,” said Sánchez during an interview with the Washington Blade from French Guiana, a French territory on the northern coast of South America. “In the past they have imposed everything on the Cuban people. They could and should incorporate gay rights, as they have done with everything in Cuba, without the need for a consultation. That is why I joined the protests. And although I was afraid, my desire for justice was greater. I went and was there. I don’t regret it and I never will. It was my duty to do my bit.”

The Cuban government prohibits unauthorized demonstrations, and those who publicly criticize it face arrest and even criminal charges.

The May 11, 2019, march took place along several busy streets near the Cuban Capitol. Police officers and state security agents infiltrated the protesters.

“At that time, I felt that I was free and that the world was listening to me and, above all, that my country was being a little freer,” Sánchez recalled. “At the end of Paseo del Prado, the march was stopped by the forces of repression.”

Sánchez began to encourage the rest of the crowd to continue marching when he felt a violent force drag him down to the ground.

“They are taking me prisoner, they are taking me prisoner,” he shouted as a state security agent tried to separate him from the crowd.

“Many people jumped in to stop that injustice, only Ariel Ruíz Urquiola (a well-known gay activist and opposition figure) and the repressors who joined in remained glued to my body. We were both led into a white police car. One of those men, when I resisted entering the patrol car, told me, ‘Bring your arm in because I am going to break it with the door.’”

Sánchez, along with Urquiola and other march participants, were taken to a police station and placed into holding cells. Sánchez was released after a number of agents interrogated him for several hours and accused him of disturbing public order.

The agents tried to get him to sign a confession, but he refused.

The witch hunt begins

That incident was only the beginning of what Sánchez describes as a “witch hunt” against him, his partner, his family and friends. Agents with Cuba’s National Revolutionary Police five days after Sánchez’s detention in Havana began to question his friends and placed his mother’s house in Quivicán, a town in Mayabeque province, under surveillance.

State security agents stopped him when he left and took him to a police station where he underwent a second interrogation.

“They told me about my life with all the details: Where I worked, where I had worked, where I studied. Everything,” Sánchez said. “They told me about my condition. They said it was not convenient for me to be involved in politics, much less interact with opposition figures, because I am a person with HIV/AIDS. They asked me why I had participated in the march. Everything was in an authoritarian and threatening tone.”

Sánchez in early June 2019 went to Ruíz’s farm. The two men met at the Havana march and had become friends. Sánchez stayed with Ruíz for approximately two weeks, and the police summoned him for another interrogation after he returned home.

“They tried to find information about him. They asked what kind of relationship I had with Ariel,” Sánchez said. “I refused to answer. One of the officers spoke to me in a threatening tone and banged on the table. I remember him telling me that Ariel was a counterrevolutionary and that relating to him also made me the same. And for that reason he could go to prison.”

The police eventually released Sánchez, but not before they threatened and intimidated him and warned him they would closely follow him.

Sánchez received antiretroviral drugs under a program that Cuba’s national health care system runs, but he said he did not get his entire monthly supply when he went to pick it up in July 2019. Sánchez made several inquiries, and was finally told a national shortage in HIV medications was the likely reason he did not receive his full regimen.

Sánchez reached out to a friend who also receives antiretroviral drugs through the same program, and he assured him that he had received all of his medications. Sánchez said he began to suspect this “missing person” was another tactic the regime used to punish him for his “rebellion.”

“After that, one of my HIV medications was missing in September and October. I knew it was its way of punishing me,” he said. “I have been an HIV patient since 2011 and since I started my treatment I have never been short. It is a simple therapy manufactured in Cuba.”

Sánchez said the owner of the house in which he lived with his partner, Diosbel Alvarez, in Havana told him that he should move because the government had decided to persecute him.

“She was aware of my political problems and I had to leave the house,” said Sánchez. “I automatically knew that she had been called or threatened, because nobody is removed because of simple comments. We realized at that moment that there were people watching outside the house.”

He said an unexpected visitor arrived at his new home shortly after he moved in. It was a state security agent who came to confirm the control the regime maintained over his life.

The agent tried to discourage Alvarez from having relationships with opposition figures inside and outside of Cuba. The agent also threatened to “deport” him to his native province because he was living illegally in Havana. (Authorities require a person who lives in Havana to have an address in the Cuban capital on their identity document.)

For Alvarez, Sánchez’s partner for more than a year and a half, the whole situation helped him become aware of the oppressive system into which he was born.

“Simply by trying to achieve equal rights and by openly demanding from the government that our social guarantees be respected, we were, and myself included, since I suffered it with him, condemned to social exile,” said Alvarez.

They were also kicked out of that house and the owner of the hostel where Sánchez worked fired him a short time later because of the regime’s pressure.

“She (the owner of the hostel) felt that she was being watched and a security officer told her that it was not convenient to have me working there,” Sánchez said. “She agreed with my way of thinking, but she was very afraid that her business would be closed.”

Sánchez and Alvarez decided that fleeing the country was the only way to stop the voracious siege under which they had lived since the march. They left Cuba for Suriname, a country that borders French Guiana, on Nov. 20, 2019.

Cubans do not need a visa to travel to Suriname.

“For me, having to abandon my country was like uprooting a tree by the roots and trying to plant it somewhere else,” Alvarez pointed out. “Leaving family and friends behind, even knowing that there is a chance of never meeting again, is a feeling that really has no explanation.

Sánchez and Alvarez lived in Suriname for approximately four months, but they decided to travel to Uruguay when they learned the country does not grant political asylum to Cubans. Immigration officials and police in neighboring Guyana robbed and threatened Sánchez and Alvarez after they crossed the border from Suriname. They traveled across Brazil and arrived in Uruguay on March 8.

Sánchez and Alvarez then asked for asylum.

“We got in touch with an association that helps people with HIV/AIDS called ASEPO, which helped my partner with his medications,” Alvarez said. “In my case, I was tested for HIV and I tested positive. They also helped me with medications to treat the disease and psychological help.”

Sánchez and Alvarez soon learned that although Uruguay provides assistance to refugees, the country does not guarantee it will grant these requests.

“In the end, years would go by under this process and that status would never be recognized,” lamented Alvarez. “Even if it were possible, it would be of no use to us, since we would never be nationalized in the country.”

With a second door closed, both decided to retrace their steps across South America and travel to French Guiana. Sánchez and Alvarez arrived in the French territory on Aug. 30.

“This is an overseas territory of France. One thinks of this country and automatically believes that it is the same as its European metropolis, but in reality that is far from it,” said Sánchez. “Although the laws and rights are the same, it is a big problem to access them.”

Sánchez and Alvarez found themselves sleeping on the street without food for four days until the French Red Cross provided them with a place to stay during their asylum process. The few LGBTQ organizations that are in French Guiana did not provide any assistance to them. Sánchez and Alvarez filed their asylum petition claim without the help of a lawyer.

“Unfortunately, the deadline to present our case to the responsible body, the French Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless Persons (OFPRA), was very short,” Alvarez explained. “Language was largely a barrier to truly expressing our story. Our request for asylum was unfairly denied because we supposedly lacked arguments and evidence to corroborate what we experienced in Cuba, despite the fact that we presented a lot of evidence.”

They are currently appealing the OFPRA’s decision to France’s National Court of Asylum Law (CNDA).

“Many people are of the opinion that the probability of being accepted and that the CNDA changes the OFPRA’s decision is low,” said Sánchez.

That uncertainty or any of the obstacles, discrimination or abuse this young couple has had to face has not stopped their search for freedom and their longing for a better future.

“We have lived the great gay odyssey,” says Sánchez. “There have been days of stress, hunger, no sleep, wanting to cry, but we don’t get tired of dreaming of finishing our training as professionals; of being citizens of some place that values its children; of being respected, of leaving discrimination behind, and above all, the stigma of having been born in a country run by corruption and indoctrination.”