This analysis focuses on whether people around the world think that homosexuality should be accepted by society or not. The full question wording was, “And which one of these comes closer to your opinion? Homosexuality should be accepted by society OR Homosexuality should not be accepted by society.”

The question is a long-term trend, first asked in the U.S. by the Pew Research Center in 1994 and globally in 2002. Respondents had an option to not answer the question (they could volunteer “don’t know” or refuse to answer the question). Respondents did not get any further instructions on how to interpret the question and no significant problems were noted during the fielding of the survey.

The term “homosexuality,” while sometimes considered anachronistic in the current era, is the most applicable and easily translatable term to use when asking this question across societies and languages and has been used in other cross-national studies, including the World Values Survey.

For this report, we used data from a survey conducted across 34 countries from May 13 to Oct. 2, 2019, totaling 38,426 respondents. The surveys were conducted face to face across Africa, Latin America and the Middle East, and on the phone in United States and Canada. In the Asia-Pacific region, face-to-face surveys were conducted in India, Indonesia and the Philippines, while phone surveys were administered in Australia, Japan and South Korea. Across Europe, the survey was conducted over the phone in France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and the UK, but face to face in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Slovakia and Ukraine.

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and the survey methodology.

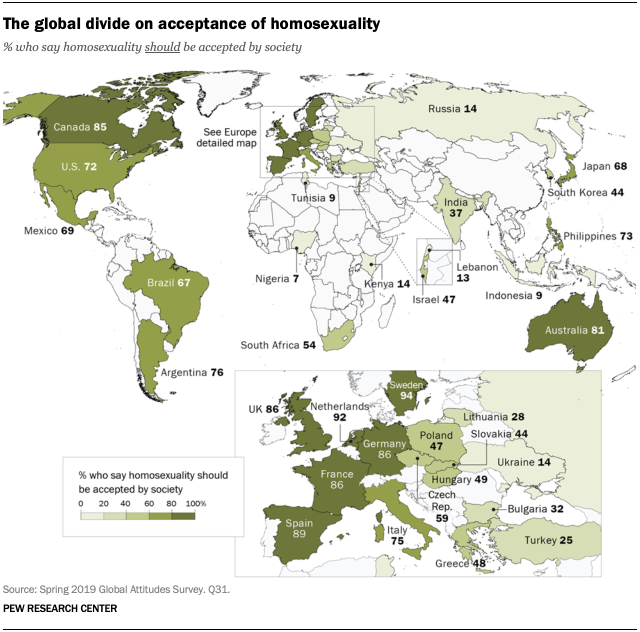

Despite major changes in laws and norms surrounding the issue of same-sex marriage and the rights of LGBT people around the world, public opinion on the acceptance of homosexuality in society remains sharply divided by country, region and economic development.

As it was in 2013, when the question was last asked, attitudes on the acceptance of homosexuality are shaped by the country in which people live. Those in Western Europe and the Americas are generally more accepting of homosexuality than are those in Eastern Europe, Russia, Ukraine, the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa. And publics in the Asia-Pacific region generally are split. This is a function not only of economic development of nations, but also religious and political attitudes.

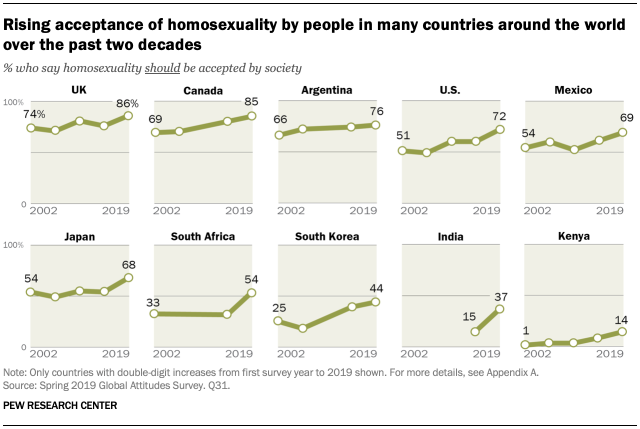

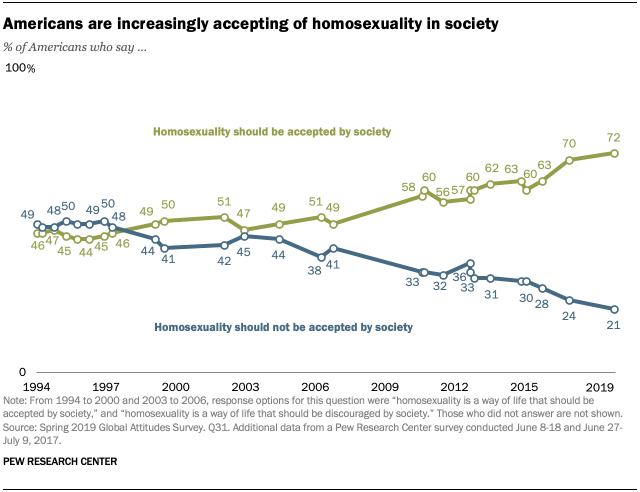

But even with these sharp divides, views are changing in many of the countries that have been surveyed since 2002, when Pew Research Center first began asking this question. In many nations, there has been an increasing acceptance of homosexuality, including in the United States, where 72% say it should be accepted, compared with just 49% as recently as 2007.

Many of the countries surveyed in 2002 and 2019 have seen a double-digit increase in acceptance of homosexuality. This includes a 21-point increase since 2002 in South Africa and a 19-point increase in South Korea over the same time period. India also saw a 22-point increase since 2014, the first time the question was asked of a nationally representative sample there.

There also have been fairly large shifts in acceptance of homosexuality over the past 17 years in two very different places: Mexico and Japan. In both countries, just over half said they accepted homosexuality in 2002, but now closer to seven-in-ten say this.

In Kenya, only 1 in 100 said homosexuality should be accepted in 2002, compared with 14% who say this now. (For more on acceptance of homosexuality over time among all the countries surveyed, see Appendix A.)

In many of the countries surveyed, there also are differences on acceptance of homosexuality by age, education, income and, in some instances, gender – and in several cases, these differences are substantial. In addition, religion and its importance in people’s lives shape opinions in many countries. For example, in some countries, those who are affiliated with a religious group tend to be less accepting of homosexuality than those who are unaffiliated (a group sometimes referred to as religious “nones”).

Political ideology also plays a role in acceptance of homosexuality. In many countries, those on the political right are less accepting of homosexuality than those on the left. And supporters of several right-wing populist parties in Europe are also less likely to see homosexuality as acceptable. (For more on how the survey defines populist parties in Europe, see Appendix B.)

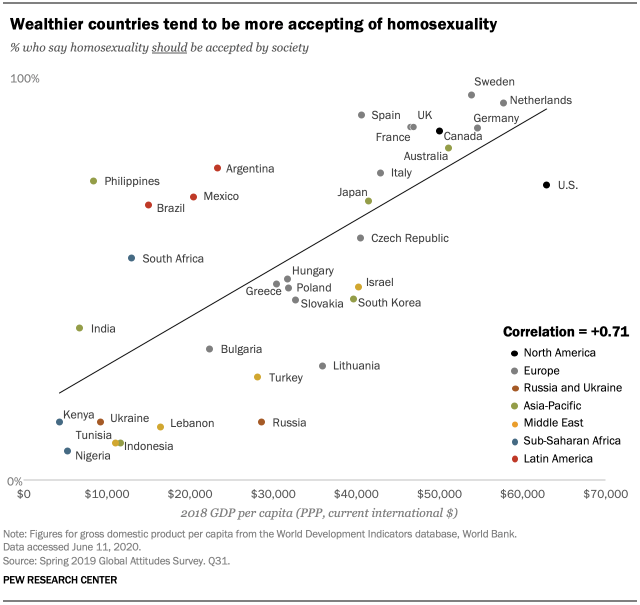

Attitudes on this issue are strongly correlated with a country’s wealth. In general, people in wealthier and more developed economies are more accepting of homosexuality than are those in less wealthy and developed economies.

For example, in Sweden, the Netherlands and Germany, all of which have a per-capita gross domestic product over $50,000, acceptance of homosexuality is among the highest measured across the 34 countries surveyed. By contrast, in Nigeria, Kenya and Ukraine, where per-capita GDP is under $10,000, less than two-in-ten say that homosexuality should be accepted by society.

For example, in Sweden, the Netherlands and Germany, all of which have a per-capita gross domestic product over $50,000, acceptance of homosexuality is among the highest measured across the 34 countries surveyed. By contrast, in Nigeria, Kenya and Ukraine, where per-capita GDP is under $10,000, less than two-in-ten say that homosexuality should be accepted by society.

These are among the major findings of a Pew Research Center survey conducted among 38,426 people in 34 countries from May 13 to Oct. 2, 2019. The study is a follow-up to a 2013 report that found many of the same patterns as seen today, although there has been an increase in acceptance of homosexuality across many of the countries surveyed in both years.

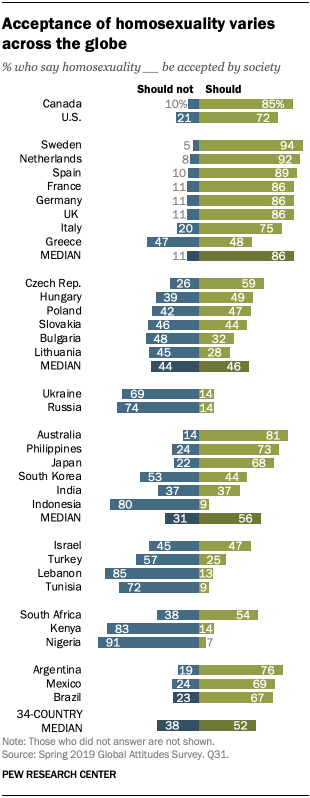

Varied levels of acceptance for homosexuality across globe

The 2019 survey shows that while majorities in 16 of the 34 countries surveyed say homosexuality should be accepted by society, global divides remain. Whereas 94% of those surveyed in Sweden say homosexuality should be accepted, only 7% of people in Nigeria say the same. Across the 34 countries surveyed, a median of 52% agree that homosexuality should be accepted with 38% saying that it should be discouraged.

The 2019 survey shows that while majorities in 16 of the 34 countries surveyed say homosexuality should be accepted by society, global divides remain. Whereas 94% of those surveyed in Sweden say homosexuality should be accepted, only 7% of people in Nigeria say the same. Across the 34 countries surveyed, a median of 52% agree that homosexuality should be accepted with 38% saying that it should be discouraged.

On a regional basis, acceptance of homosexuality is highest in Western Europe and North America. Central and Eastern Europeans, however, are more divided on the subject, with a median of 46% who say homosexuality should be accepted and 44% saying it should not be.

But in sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, Russia and Ukraine, few say that society should accept homosexuality; only in South Africa (54%) and Israel (47%) do more than a quarter hold this view.

People in the Asia-Pacific region show little consensus on the subject. More than three-quarters of those surveyed in Australia (81%) say homosexuality should be accepted, as do 73% of Filipinos. Meanwhile, only 9% in Indonesia agree.

In the three Latin American countries surveyed, strong majorities say they accept homosexuality in society.

Pew Research Center has been gathering data on acceptance of homosexuality in the U.S. since 1994, and there has been a relatively steady increase in the share who say that homosexuality should be accepted by society since 2000. However, while it took nearly 15 years for acceptance to rise 13 points from 2000 to just before the federal legalization of gay marriage in June 2015, there was a near equal rise in acceptance in just the four years since legalization.

While acceptance has increased over the past two decades, the partisan divide on homosexuality in the U.S. is wide. More than eight-in-ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (85%) say homosexuality should be accepted, but only 58% of Republicans and Republican leaners say the same.

While acceptance has increased over the past two decades, the partisan divide on homosexuality in the U.S. is wide. More than eight-in-ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (85%) say homosexuality should be accepted, but only 58% of Republicans and Republican leaners say the same.

At the same time, the U.S. still maintains one of the lowest rates of acceptance among the Western European and North and South American countries surveyed. (For more on American views of homosexuality, LGBT issues and same-sex marriage, see Pew Research Center’s topic page here; U.S. political and partisan views on this topic can be found here.)

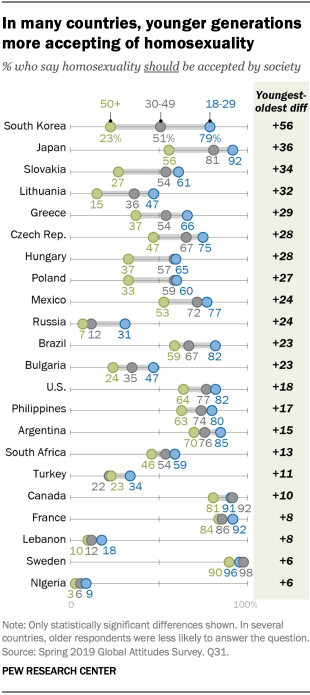

In 22 of 34 countries surveyed, younger adults are significantly more likely than their older counterparts to say homosexuality should be accepted by society.

In 22 of 34 countries surveyed, younger adults are significantly more likely than their older counterparts to say homosexuality should be accepted by society.

This difference was most pronounced in South Korea, where 79% of 18- to 29-year-olds say homosexuality should be accepted by society, compared with only 23% of those 50 and older. This staggering 56-point difference exceeds the next largest difference in Japan by 20 points, where 92% and 56% of those ages 18 to 29 and 50 and older, respectively, say homosexuality should be accepted by society.

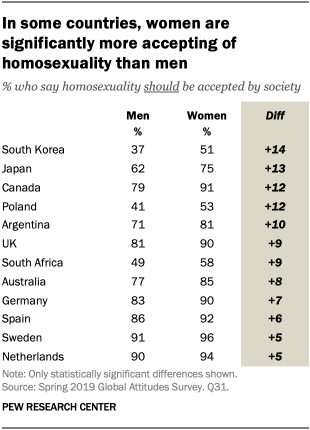

In most of the countries surveyed, there are no significant differences between men and women. However, for all 12 countries surveyed where there was significant difference, women were more likely to approve of homosexuality than men. South Korea shows the largest divide, with 51% of women and 37% of men saying homosexuality should be accepted by society.

In most of the countries surveyed, there are no significant differences between men and women. However, for all 12 countries surveyed where there was significant difference, women were more likely to approve of homosexuality than men. South Korea shows the largest divide, with 51% of women and 37% of men saying homosexuality should be accepted by society.

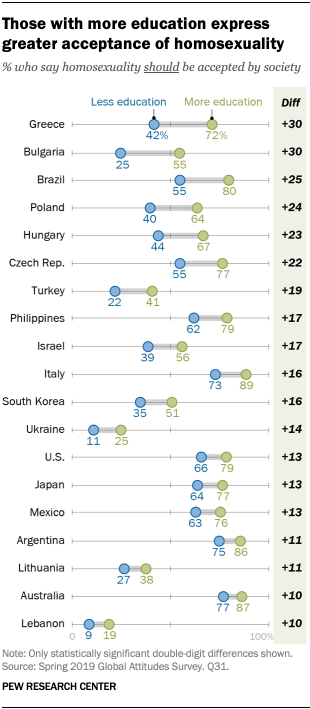

In most countries surveyed, those who have greater levels of education are significantly more likely to say that homosexuality should be accepted in society than those who have less education.

In most countries surveyed, those who have greater levels of education are significantly more likely to say that homosexuality should be accepted in society than those who have less education.

For example, in Greece, 72% of those with a postsecondary education or more say homosexuality is acceptable, compared with 42% of those with a secondary education or less who say this. Significant differences of this nature are found in both countries with generally high levels of acceptance (such as Italy) and low levels (like Ukraine).

In a similar number of countries, those who earn more money than the country’s national median income also are more likely to say they accept homosexuality in society than those who earn less. In Israel, for instance, 52% of higher income earners say homosexuality is acceptable in society versus only three-in-ten of lower income earners who say the same.

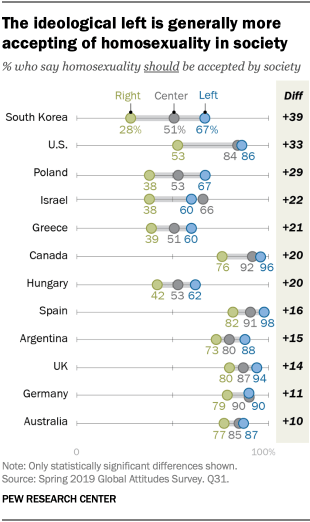

In many of the countries where there are measurements of ideology on a left-right scale, those on the left tend to be more accepting of homosexuality than those on the ideological right. And in many cases the differences are quite large.

In many of the countries where there are measurements of ideology on a left-right scale, those on the left tend to be more accepting of homosexuality than those on the ideological right. And in many cases the differences are quite large.

In South Korea, for example, those who classify themselves on the ideological left are more than twice as likely to say homosexuality is acceptable than those on the ideological right (a 39-percentage-point difference). Similar double-digit differences of this nature appear in many European and North American countries.

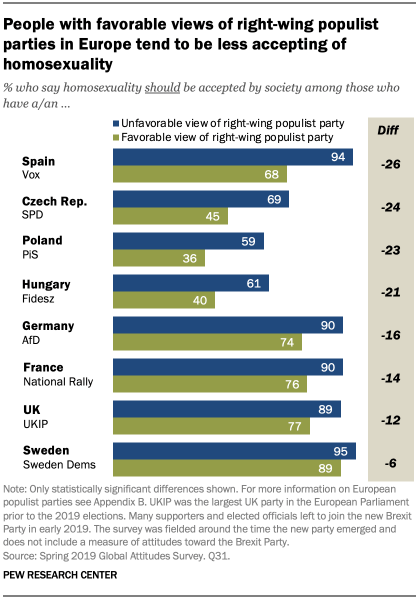

In a similar vein, those who support right-wing populist parties in Europe, many of which are seen by LGBT groups as a threat to their rights, are less supportive of homosexuality in society. In Spain, people with a favorable opinion of the Vox party, which recently has begun to oppose some gay rights, are much less likely to say that homosexuality is acceptable than those who do not support the party.

In a similar vein, those who support right-wing populist parties in Europe, many of which are seen by LGBT groups as a threat to their rights, are less supportive of homosexuality in society. In Spain, people with a favorable opinion of the Vox party, which recently has begun to oppose some gay rights, are much less likely to say that homosexuality is acceptable than those who do not support the party.

And in Poland, supporters of the governing PiS (Law and Justice), which has explicitly targeted gay rights as anathema to traditional Polish values, are 23 percentage points less likely to say that homosexuality should be accepted by society than those who do not support the governing party.

Similar differences appear in neighboring Hungary, where the ruling Fidesz party, led by Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, also has shown hostility to gay rights. But even in countries like France and Germany where acceptance of homosexuality is high, there are differences between supporters and non-supporters of key right-wing populist parties such as National Rally in France and Alternative for Germany (AfD).

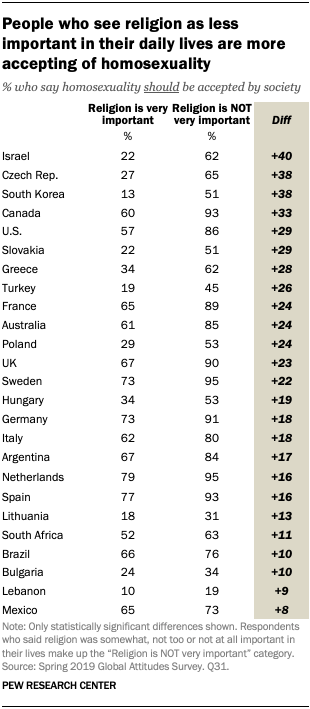

Religion, both as it relates to relative importance in people’s lives and actual religious affiliation, also plays a large role in perceptions of the acceptability of homosexuality in many societies across the globe.

Religion, both as it relates to relative importance in people’s lives and actual religious affiliation, also plays a large role in perceptions of the acceptability of homosexuality in many societies across the globe.

In 25 of the 34 countries surveyed, those who say religion is “somewhat,” “not too” or “not at all” important in their lives are more likely to say that homosexuality should be accepted than those who say religion is “very” important. Among Israelis, those who say religion is not very important in their lives are almost three times more likely than those who say religion is very important to say that society should accept homosexuality.

Significant differences of this nature appear across a broad spectrum of both highly religious and less religious countries, including Czech Republic (38-percentage-point difference), South Korea (38), Canada (33), the U.S. (29), Slovakia (29), Greece (28) and Turkey (26).

Religious affiliation also plays a key role in views towards acceptance of homosexuality. For example, those who are religiously unaffiliated, sometimes called religious “nones,” (that is, those who identify as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular”) tend to be more accepting of homosexuality. Though the opinions of religiously unaffiliated people can vary widely, in virtually every country surveyed with a sufficient number of unaffiliated respondents, “nones” are more accepting of homosexuality than the affiliated. In most cases, the affiliated comparison group is made up of Christians. But even among Christians, Catholics are more likely to accept homosexuality than Protestants and evangelicals in many countries with enough adherents for analysis.

One example of this pattern can be found in South Korea. Koreans who are religiously unaffiliated are about twice as likely to say that homosexuality should be accepted by society (60%) as those who are Christian (24%) or Buddhist (31%). Similarly, in Hungary, 62% of “nones” say society should accept homosexuality, compared with only 48% of Catholics.

In the few countries surveyed with Muslim populations large enough for analysis, acceptance of homosexuality is particularly low among adherents of Islam. But in Nigeria, for example, acceptance of homosexuality is low among Christians and Muslims alike (6% and 8%, respectively). Jews in Israel are much more likely to say that homosexuality is acceptable than Israeli Muslims (53% and 17%, respectively).