IN THE MID-1990s, Argentina was again in a recession. The government had anticipated the country would become rich thanks to the free-market policies of president Carlos Menem (the economy did grow — along with unemployment), but austerity and privatization exacted a heavy toll, and instead it became poorer. In Buenos Aires, one in four households lived below the poverty line, and toward the end of the decade, according The Washington Post, an average of two banks were being robbed a day. Basic government services, such as pensions, health care, even jails (prisoners were placed in abandoned factories for lack of space) had run out of money. In her story “Congreso, 1994,” the Argentine writer Cecilia Pavón hints at some of the material conditions of the time, albeit in a state that verges on rapture, superimposing the beauty of nature onto a blighted urban landscape. “Walking along Hipolito Irigoyen Street on dark, poorly lit nights is like walking through a forest,” she writes:

The dry plazas and uneven sidewalks are just like the wilderness of the Andes. […] [W]hat I love most about this neighborhood is its frequent blackouts. When all the house-hold appliances stop working — and the elevator, too — I run down the nine flights of stairs separating me from the ground floor. […] When the lights go out, the city becomes like a cave, and the light from the cars becomes the beating of a chaotic, arrhythmic heart. A heart that is deformed, monstrous, like the sounds of the city.

It is by listening to techno music in the clubs of Congreso, a neighborhood in Buenos Aires “full of offices and devoid of children,” that she is able to hear such sounds in a different way. They do not become less horrible, but through the conditioning of art she learns how to appreciate them: “Whenever I feel like that noise is wounding my soul, I say, ‘It’s not wounding it, it’s giving it joy. Noise is pleasure, like Daft Punk’s music.’”

As with nearly all of Pavón’s work — both stories, often just a few pages long, and a profusion of poems — “Congreso, 1994” is a gnomic mixture of irony, enchantment, sincerity, melancholy, and humor. Neither a slavish realist nor a full-blown fabulist, Pavón fashions her (with a few exceptions) “I’s” experience of the world in a register that is hard to pin down. Her narrators seem unassuming yet fearless, acutely receptive to both the beauty and noxiousness of life; impassioned, they can also be insouciant and deadpan: “It’s a mystery how girlfriends disappear,” one says in a story that begins with the dissolution of a group of women friends and evolves into a litany of accessories. “I spent months remembering them all the time until I got tired of thinking about them, too, and decided to put my mind to other things. Like every bag I’ve ever owned.”

My friend, the poet and translator Stuart Krimko, first introduced me to Pavón’s work through his English translations. He notes that Pavón’s writing “almost always foregrounds the immediacy of her emotions, even as it meditates on aesthetic themes or reveals a disarmingly precise sense of structure and timing.” Indeed, in her fiction Pavón constructs space for her narrators to think and feel in equal measure, resulting in beguiling revelations, which are always surprising even when the action of a story falls flat. As with Dorothea Lasky and Sheila Heti, Pavón prefers to use a bold and direct persona that is allowed to express all kinds of contradictions, a voice intoxicatingly and powerfully free.

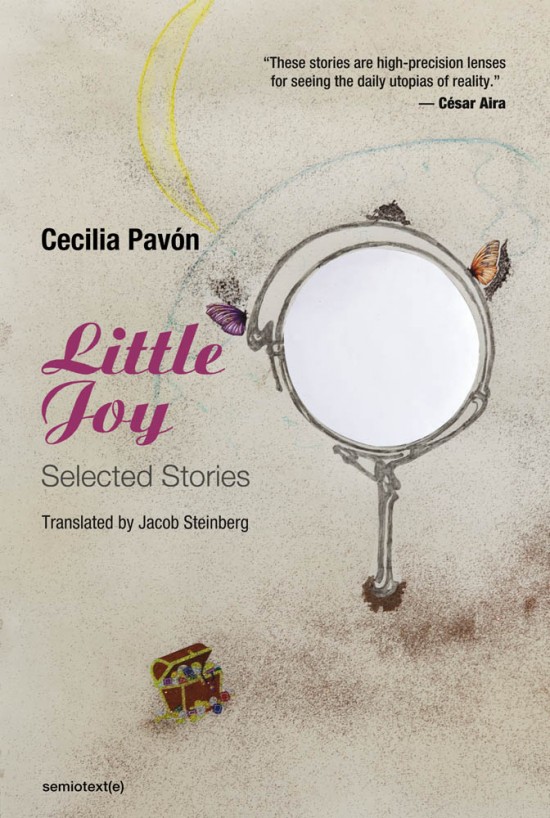

It’s easy to locate this voice in Little Joy, the first full collection of Pavón’s stories to be published in English. Translated by Jacob Steinberg, the book consists of 35 stories (alas, they are not dated) spanning three decades of Pavón’s writing from 1999 up until the present. After moving to Buenos Aires from Mendoza to study literature at university in 1992, around the time the first pieces in this collection were written, Pavón, along with the artist and writer Fernanda Laguna, founded the exhibition space and publisher Belleza y Felicidad (ByF), whose name seems yet another indication of her sensibility. Described by the writer César Aira as a “complete program of resistance,” Belleza y Felicidad proved to be an oasis for the creative community in the difficult years leading up to the worst financial crisis in Argentina’s history, in 2001. But how not to also read a bit of acid into christening a space Beauty and Happiness when, at the hands of an incompetent government, so much of the country was in despair?

Belleza y Felicidad served as gallery and also, in a kind of play on the word, a regaleria, or gift shop. It sold art supplies and inexpensive trinkets (“cheap, horrible things that were beautiful” as Pavón said recently in a talk at Art Center College) bought at local dollar stores. The space’s inaugural exhibition took place during the first gay pride parade in Buenos Aires: gay poets’ lines were printed on handkerchiefs and hung in the windows of ByF, which stood on the parade’s route. There were music shows and readings, as well as a monthly in-house magazine, and the events drew both artists and neighbors alike. Importantly for Pavón and her fellow writers, ByF provided an experimental and free-form literary venue: at a time when the production of books had decreased precipitously in Argentina, Pavón and Laguna ignited an alternative model of publishing, producing crudely crafted volumes that were often just Xeroxed pages stapled together, like zines, wrapped in a plastic bag, and accompanied by a little plastic charm. Early titles included Pablo Perez’s El Mendigo Chupapijas (The Cock-Sucking Beggar); an anthology of queer writing titled Aventura; Laguna’s book Tatuada para siempre (Tatooed Forever), published under the pen name Dalia Rosetti; and Pavón’s Virgen.

Some of the spirit of this scene is captured in Pavón’s stories, which are told from within art and literary realms, whether it be the informal ones of dance circles, weekly writing workshops, and one’s own room, or more institutional iterations like museum shows and international conferences. It’s the latter sphere with which the narrators often find themselves morally or temperamentally at odds. “I won’t be able to create that work of art entailing 320 pounds of raw meat thrown against the gallery wall,” the addresser of “Dear Johanna” begins. “Food has become a luxury item.” The commerce of art is always suspect — “Dreams Can’t Be Copyrighted” is one of the titles here — and Pavón returns more than a few times to the tension between the wealthier echelons of the art world and the more impecunious life of poets and translators (which Pavón is herself), in addition to the economic gulf that divides the cultural elites of Europe and Argentina. The “trivial” theft of a bottle of Vichy makeup remover from a “European, a.k.a., somebody rich” in one story is “not only less vile but even kind of heroic.” Another ends with the irreverent wish to “have a room full of euros, floor to ceiling, to go in during the early morning hours when everything is still dark and step on them. I’d grab fistfuls without even checking how much and stuff them in my guests’ pockets.”

Pavón is perhaps at her most transcendent, though, when describing or enacting the creative process itself — be it learning about a new poet and translating her work into Spanish, or transcribing lines from bad reality television, or more ambitiously, dressing up in fat suits in search of undiscovered emotions. As much as Pavón posits in her work that writing should be born of admiration or love (“Any writing that doesn’t move towards love will crash against a wall or something else hard, like that one time a train coming into Once Station didn’t brake,” goes the memorable opener of “A Perfect Day”), the love of writing or creating art also seems to constitute an opposition to everything else, making its pursuit a form of political resistance. This is particularly true in regards to historically feminine experience, such as consumerism or the monitoring of personal appearance, as in the story “Losing Weight.” After a complex commentary on the ways in which class and body types intersect, the narrator, inspired by her friend Tini, decides to start a diet. A few months in, though, she reconsiders: “The idea of achieving aesthetic and spiritual sovereignty through food wasn’t as easy as I thought it would be. And what if, instead of eating well, I commit to writing better?” “I must write well,” she repeats over and over. “I’m going to call Tini to tell her that we must write well.” For Pavón, writing is more than simply an aesthetic exercise: “To write is to accept the wear and tear of objects.” It is also imbued with the power to metabolize the world: “Life only exists to be consumed by poetry,” says the narrator of “Types of Plastic,” “like an iron pole knocked down by the mystery of rust.”

It’s thrilling how casually some of these stories slip into utopia. One of my favorites in the collection is “Nuns, the Utopia of a World Without Men,” where two women decide, out of the blue, to travel to a convent, even though one of them asks herself on the bus ride there, looking out at “the stars through the frosted window,” why she wants to be a nun when she can’t even bring herself to pray. Still, once inside the convent, she finds an antidote to the demands of work and city life, a group marriage to God so radical it would never be recognized by the Buenos Aires registry, and erotic fulfillment with another nun. Occasionally and without preamble, Pavón places her stories in a future time when people look back at the limits of religion or monogamy, and wonder innocently how their forebears dealt with antiquated emotions like jealousy or the quest for the eternal. In a much darker story, semi-benign aliens have landed in the Americas, obliterating all culture, but even here the narrator finds a “Little Joy (Temporary Autonomous Zone),” as the title goes: a space in an old antique shop filled with books.

Beyond their future imaginings, Pavón’s stories seem to offer some sense of how we might live now, with all the terror and wreckage currently in front of us. Indeed, seizing some beauty or happiness even in ugly things may be one of the few viable strategies still available to us. “Initially we didn’t know whether to laugh or cry,” a narrator says in a story early in the book, upon seeing a menacing cloud on the horizon.

While neither of us said it, we both thought it was probably something toxic: a war, an attack, an explosion at some run-down factory. But at the same time, there was something fascinating about the way the mass cleared a path, painting absurd shapes in the sky in just fractions of a second. It was exciting, because it was strange … and big. And it was in the sky.

¤